GUT SHOT

Dom’s scheduled to give a talk at some PTA meeting the day after the memorial service. It’s for parents of high schoolers, and he wants me to go with him. Apparently, most people are bringing their kids. I guess they don’t want to risk leaving them home to be murdered.

“Come on, Cactus, time to skedaddle.”

I groan and tell Dom I’d rather stay at the Great Moose Motel and shove pencils in my eyeballs than listen to him embarrass me in front of the entire town. Then I crawl into my double bed and pull the covers over my face, hoping he’ll leave without me.

“I love you, Huggersmith,” he says.

“My stomach hurts,” I grumble.

For one thing I don’t really feel like running into any more tear-stained faces, especially when I can’t seem to wipe this angry look off my own face. Plus, Dom let it slip he’ll be giving a speech today titled “Hugging Your Teenager.” He was always doing stuff like that when I was in middle school. Once for an assembly, he got onstage in front of the whole sixth grade and gave a presentation called “Love Your Body While It Changes!” There were illustrated diagrams and a mannequin, and Dom kept winking at me the entire time. It was terrible.

“Everything you’re feeling is valid, Kipster,” Dom says, putting on his counselor voice. I hear his knees crack as he crouches beside my bed. “Go on, talk at me, honey, it doesn’t have to be all pretty.”

I peek out at him from underneath the blankets. “I guess I wish you’d fart outside,” I say. “I mean, that’s where I’d start, if I started expressing myself.”

“Okay, so you’re deflecting, I get that, you betcha.” He plucks his phone out of its belt holster. “And you can stay here while I’m out, but not by yourself—no way, no how.”

So now Ralph is coming over.

Ralph Johnston has been keeping an eye on me since Mom died—which basically means he’s been my babysitter since he was two years younger than I am now. So it doesn’t really make sense that I’m not old enough to look after myself, and there’s definitely grounds for raising my voice about how unfair Dom is being. But I don’t feel like arguing.

Plus, it’s Ralph. He’s lived across the street from me my whole life, and if it weren’t for the age difference I’d probably just call him my second best friend . . . or promote him to hypothetical first best friend, since Ruth could give a crap. Basically I have no friends.

Ralph actually called last night to say sorry for not coming to Ruth’s memorial service. He obviously knew her pretty well—or at least, he’d exchanged basic pleasantries with her for the nine years she and I were inseparable—and so he’d barely known her for a long time. Anyway, on the phone last night he said he was sorry, but that when it came down to it he just wasn’t ready to go back to Cutter Funeral Home.

“I dragged my heels,” he said. “I wasn’t brave enough to leave the house.”

And I couldn’t argue with that. Ralph’s parents were like family to me—but when it was time for their funeral last winter, I locked myself in the bathroom and pretended to be throwing up until Dom relented and let me stay home unchaperoned. At that point it had been eight years, nine months, and four days since Mom had died. So I can’t even imagine how Ralph must have felt about returning to Cutter less than a year after both his parents were displayed there.

“No worries,” I told him. “You didn’t miss much except me mucking up.”

The last time Ralph and I were at Cutter Funeral Home together was when he and his parents went with Dom and me to pick up Mom’s ashes. For moral support, or whatever. I remember being downstairs while everyone else went up to help Dom fill out the paperwork. People had been holding me on their laps for weeks, and I hadn’t gotten to see her yet all by myself. Standing there with her ashes was the first time I fully realized how different it would be without her. I had been momentarily forgotten, left alone with a bag of ground-up bones. And Mom would never have allowed that. Even if the bones were hers.

Anyway, I couldn’t stop touching them. The ashes, I mean. I opened the bag and grabbed handfuls. And by the time Ralph trotted down looking for me, I was elbow deep in remains. I caught his eye and froze. I was so afraid that Ralph, who was older, would tell on me, or make a face like I was gross—I mean, who tries to hug their mom after she’s been pulverized? But instead he just said, “Yeah, it’s like construction rubble, huh?” It was. Like gravel or a bag of broken shells.

And that’s the thing about Ralph: he’s not judgmental. He never has been. I can’t really put my finger on it, but I think it has to do with the fact that he’s really good with computers. Like, it makes him look at the world differently, because he can break a problem into pieces—and when you’re zooming in on yourself, he can zoom you back out.

The point is, we get along, and I’ve never felt self-conscious around him, and I can’t say that about most people. I can wear what I want and say what I will, and ask dumb questions and mess up. But he never thinks I’m weird or what some might call a loser.

“Jesus, Kippy Bushman,” Ralph whines when I open the door. He’s got on a matching Windbreaker set and those wrap-around sunglasses that ESPN poker players wear. He used to wear the same thing every day: baggy jeans and funny, screen-printed T-shirts—with real zingers on them like Eat Sleep Code or I can explain it to you but I can’t understand it for you. But ever since he took a break from computers, this is his new uniform.

I smile. “Hi, Ralph Johnston.” First things first, I try to figure out which of his eyes is pointed at me, and then I stare at it. I think most people just don’t make eye contact with Ralph because it’s easier, but I always want him to know that his lazy eye is cool with me. “Nice purple Windbreaker. You look like a mafia wife.”

“That’s fine. Listen, I really need to get started on some things, is that okay?” His arms are full of electronics—some Xbox controllers and a bunch of games, still in the wrappings. Before Ralph got so into video games, engineering programs and tech schools all over Wisconsin and even outside the state were sending him postcards to apply. But Ralph dragged his feet, and then Mr. and Mrs. Johnston died, and Ralph inherited the house, and suddenly he wouldn’t code at all anymore. He started buying collectibles and weird figurines. And then he bought all these Windbreaker sets and started with the video games. The only reason he goes on the computer anymore is to buy more stuff.

Sometimes I worry about him, but then I remind myself that what he’s going through is all part of the process. After Mom died I got obsessed with all sorts of weird things—from good-luck troll dolls, to step-by-step strategies on how to wrestle an alligator or a great white shark, if one should get you. Survival, basically. It goes in cycles. After becoming well versed in different sorts of animal attacks I started getting into people I could emulate. Batman. Harriet Tubman. Harriet the Spy. All Dom’s books concur that your mind goes through phases like that to distract itself. You’ve just got to be patient, really, and allow for ample rehabilitation time.

“Kippy, sorry, but you’re literally blocking the door.”

I move aside, mumbling apologies.

“Thank you.” Ralph shifts under the weight of his electronics, and one of his controllers falls onto the carpet. “Jesus. Could you show me where to plug in, is that all right?” Ralph has this frantic, apologetic way of talking—always on full volume. Ruth once called him an obnoxiously polite emergency siren. “Danger! Tornado! Is that all right?” I think part of her wanted to be my only friend, because sometimes she’d ask me what I even needed Ralph for. It always felt too pathetic to say, “Because he never ditches me like you do.”

“There’s one right here, but I don’t know how to set it up,” I say, directing Ralph to the bedroom TV. “There’s another one in the bathroom for some reason, but it’s mounted on the wall.”

He grins. “I call this one.”

“Is that Ralph?” Dom calls from inside the bathroom. A toilet flushes.

“Dominic Bushman,” Ralph shouts, struggling out of his sneakers. “I would give you a high five, except you’re in the bathroom and I have all these electronics to deal with. I’m actually very busy, is that all right?” He falls onto his knees in front of the television and carefully removes and folds his sunglasses, then begins untangling the cords. His Windbreaker crinkles and gasps.

Dom opens the bathroom door, wiping his hands on his pants. “I can see that, Ralph.” He looks nervously around the room. “Keys, keys, keys.”

“They’re in your coat,” I tell him.

He claps once, grabbing up his coat, and winks at me. “Call my cell if you need me, Pimple,” he says, and touches my head as he swoops past me out the door. “I’ll be home around three.” The door slams behind him and I lock it like I’ve been told to.

“Listen, Kippy.” Ralph changes the input on the television. “I think you should use the bathroom television to watch the local channel, is that all right?” He uses a controller to outfit a medieval, gnomish character on the screen with facial hair, ammunition, and armor. “Sheriff Staake is supposed to make an announcement today.”

I can feel my pulse in my neck. “About what?” If they’ve got the killer, then it’s over and we get to go home. “Did they find someone?”

“Jesus, Kippy, I don’t know—that’s why one of us needs to keep an eye on Channel Five.” Ralph gapes at me and one of his eyes rolls slightly to the left. “But you betcha that’s what I think, and I’m certainly relieved about it, too—ten more seconds with this town’s new fright and I’d be sleeping on a cot in here with you and Dom. It’s jittery at home.” He shivers, then switches the controller to one hand and roots around in his pocket, pulling out a small doll. “Also I brought this for you.”

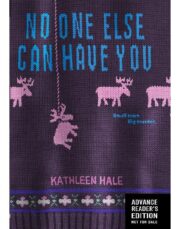

"No One Else Can Have You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No One Else Can Have You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No One Else Can Have You" друзьям в соцсетях.