“Ah cripes, Ralph,” I say, seeing it’s one of his cherished Norse collectibles. “I can’t take that one, it’s your favorite.”

“Kippy!” Ralph scolds, throwing down his controller. “Thor is associated with thunder, lightning, storms, oak trees, strength, destruction, healing, and the protection of mankind.” He holds up the Thor doll, shaking its beard in my direction. “I want you to feel better.”

I take the gift and try to handle it in a way that reflects its proposed worth. Kind of like I’m accepting a sword. I usually don’t love Ralph giving me presents because I worry he’s going to run out of his parents’ inheritance. I know it takes time to get loss out of your system—or at least to build up enough emotional scar tissue so you can go through the motions and be who you were before everything went wrong. But when Ralph snaps out of it I want him to have enough money left to go to college like he’d planned. Back when he first graduated high school he told everyone that the applications were too much pressure—that he’d get to them later. Then a few years passed and all of this stuff happened. But he might still go.

“Okay,” I say, rubbing Thor’s beard with my thumb. I glance at Ralph, who seems uncomfortable—we’ve been through four deaths at this point, but we don’t really talk about feelings, and that’s how we both like it. So I try to think of a question that will make him feel important and distract us both. One great thing about Ralph is that he’s spent so much time on the internet that he’s kind of like a human Wikipedia, so I tend to go to him whenever I need facts. Like for school papers, or because I haven’t talked to him for a while, or something. “Um hey, what’s with all these ladybugs?” I point to the reddish dots lounging on our walls. Tons of them get indoors every fall, but I’ve never asked about it. The whole time we’ve been at the Great Moose, they’ve made it feel like camping.

“Hmph.” Ralph snaps to attention, scanning the room. “Well, Kippy, you know autumn is a funny time for insects, it turns out. Not only is the environment getting cold, but also their lifespan is coming to an end. They fly inside seeking warmth, not knowing what’s happening.” He shrugs. “They come in here to die.”

“Huh,” I say. “Thanks.” I start toward the bathroom to turn on the other television, but Ralph calls after me, and I spin around in the doorway.

“I want to tell you that I’m sorry for your loss,” he says, looking at his knees. “I know that’s a thing people say, and you’re probably sick of hearing it. I mean, it gets exhausting—heck I know it. So I’m not going to say anything else about it except for ‘I know it hurts, and I’m right across the street.’” He clears his throat. “Also, ‘Anything you want to be, you can come be that with me. Rain or shine, no problem.’”

My eyes burn and I taste metal. Anything you want to be, you can come be that with us. Rain or shine, no problem. It’s what Mr. and Mrs. Johnston used to say to me after Mom died. And it was a big deal, too, because in Friendship, people just want to ignore the bad stuff and keep on bringing food until it all goes away and we can return to our pleasantries—our “How’s by you?” and “What about this weather?” Around here, it’s a big deal to acknowledge someone’s sadness with your words.

I gesture slightly with the Thor doll. “Thanks,” I say, and shut the bathroom door so I can cry.

After Mom’s funeral, there was a period I barely remember when Dom didn’t want to get out of bed or even talk to me, and Ralph’s parents would come by and drag him outside with them, and force him to go for a walk. After a few seconds of trying to shake them off, he’d just go blank—turn pale and dead faced—and let himself be led around by the elbows.

I was never alone during those walks. Ralph was already really good at gadgets then, and usually while his parents were taking care of Dom, he’d wave me over into his garage and let me sit on one of the folding chairs while he took apart old calculators and put them back together. Sometimes we’d go inside and I’d watch him play Lemmings, which was this old computer game where you had to guide little green guys through a sort of maze so they wouldn’t kill themselves, which is what lemmings do. After a while I started to look forward to our hangouts so much that I’d go and sit on my front lawn whenever I saw that he was home. I’d pretend to be doing something until he saw me and took the hint and waved. I don’t remember how long it took for him to switch from calculators to computers, just that one day I came over and there was a giant PC splayed out in pieces on the dusty concrete. And he wasn’t taking it apart, either. He was building it from scratch.

In retrospect, I’m sure Mr. and Mrs. Johnston were behind Ralph’s hollered invitations, at least at first. They were behind everything back then. They came over to make sure I was awake in time for school, then brushed my hair and waited with me at the bus stop. They mowed our lawn and shoveled our driveway, brought us baked French toast in the morning and casserole at night. For a long time I’d look out at their porch light just before bed and our house would feel a lot less empty.

They did that for a whole school year. After that it went back to normal, and they didn’t cook for us, and they didn’t come over so often. They retreated back into their own lives out of politeness, because anything else would have said we couldn’t look after ourselves, and we grew apart again except for pleasantries. But Ralph would still wave me over when I was out in the lawn, or I’d come around looking for him. And every so often Dom would work late and Ralph would stop by and make me popcorn.

Now that I think of it, I’m not sure if we ever told Mr. and Mrs. Johnston thank you, but after they died, we did give Ralph our full attention, which Dom assured me was the same thing if not better than a Hallmark card with gratitude scribbled all over it. Ralph stayed at our place a lot, because he said his smelled too much like home. He’d wander around our living room, tottering like a baby, clutching photos of his folks. We understood. But eventually Dom confiscated all Ralph’s family albums because he didn’t want him to ruin the pictures through too much accidental crumpling.

“You’ll thank me later, buddy,” Dom told him.

The whole thing was really tragic. I mean, Mr. and Mrs. Johnston were older, as far as parents go, but they didn’t die of natural causes. They hit a deer on the highway. A ten-point buck. Apparently it didn’t die right away and kept twisting its neck around. It broke their windshield and gored them with its antlers before they could grab their shotgun from the backseat. A few months later, I was driving with Ralph and we hit a deer, too—we were fine, but the deer wasn’t. It was up on the hood of the truck, bleeding more than you’d expect—even from an animal that big. Its head was lolling and it was screaming. The thing about animals is that they shriek when they’re hurt. I’ve only heard the sound a couple times but I’m pretty sure the terribleness of it has something to do with the fact that every kid in Friendship except me (I wanted nothing to do with it) gets taught how to shoot an animal through the neck or the head. Anything else is called a gut shot and creates an awful noise. Not to mention it ruins the meat.

Anyway, if I’d have been Ralph, I would have freaked seeing a half-dead deer two months after the same type of animal had basically murdered my parents. But he was strong about it—really courageous—probably for my sake, actually, knowing him. He just got out of the car, grabbed the shotgun from the backseat, told me to cover my eyes, and shot the thing right through the face.

Later, he sold his truck for parts instead of waiting for repairs, which I thought made sense. Better to start fresh, in my opinion. He drives a minivan now.

Anyway that’s why hunting is like Mardi Gras around here—not just because people think it’s fun, but because otherwise the deer die of starvation or we hit them with our cars. It’s more humane for everyone involved if we simply murder them. Most of the cars in the high school parking lot are dented and have bumper stickers that read Hunting Is Heroic.

I’ve got the remote between my feet, my eyes peeled on Channel 5. Usually the local TV channel is reserved for high school football scores or bake sale announcements blared in text across a bright-green screen, but Sheriff Staake said to stay tuned.

“We’ve learned a bundle in the past few days,” he said a little while ago, his friendly pink face scrunching up left and right. “School should be back in session soon, that’s all I’m gonna say. But hear you me, pretty soon we’re all gonna give a big sigh of relief.” He smiled, his face lit up like a jack-o’-lantern. “We’ll be releasing all the details in about a half hour. Keep us in your crosshairs.”

The idea that local police are trying to figure this out is pretty crazy. I mean, you’d think they’d get the FBI. I’m not saying Friendship cops are stupid, just that they’re not used to something this serious. It feels like most of the time they’re either staking out the dam for radical Islamic terrorists or perpetuating false rumors about razor blades in apples. The only time I ever really saw them hustle was when I got my hand stuck in the tampon dispenser. The whole squad turned up, Jaws of Life and everything.

I glance at my watch—ten minutes until Staake’s announcement—and flip open my laptop to watch clips of Diane Sawyer. For whatever reason she calms me down.

“In other news, a black widow spider was found in an elementary school in Kansas today,” she says, frowning slightly. “Luckily, a janitor found the deadly arachnid before any innocent children did.”

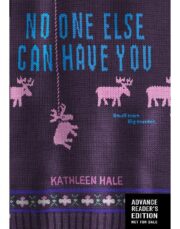

"No One Else Can Have You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No One Else Can Have You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No One Else Can Have You" друзьям в соцсетях.