I turn to Friday and there’s nothing. The last entry is a Venn diagram. I can’t really read it, but I’m pretty sure it’s comparing Colt’s and Jim Steele’s penises, which are both apparently huge (the overlapping part says “=huge,” with penis drawings). I shove the diary back into my bag.

“But the thing that really gets me,” Davey is saying, “is how my sister was a solid, surly girl—the kind of kid I could punk around, you know? But they could tell by the lack of marks on her body that she didn’t fight back. When it came down to it, she let herself be dragged. Just went limp and let herself be pulled out to that big old tree.” Davey starts to cry so he can hardly get the words out. It’s a crappy, violent sight. “She must have been so scared. . . . It must have been so bad that she just gave up.”

I try to imagine Ruth looking up at the stars, getting hauled through the corn. What could she have been thinking at the end except, “I want to go home, I want to go home”? I feel too sick to cry because it’s all my fault—the thought comes floating back to me like the shadow of a plane about to drop a bomb. I was so mad at her for those first few hours when she didn’t show up at my door. She was supposed to come at 8 p.m. Friday night sleepover. By nine, I thought she’d ditched me for Colt again. By eleven, I thought she was a dick. The next morning, I finally buckled and called Mrs. Fried, who called the police. But at that point, Mrs. Schultz had already stopped by the field to check her crops. Pretty soon, cop cars and an ambulance were clogging up our street. And after a while, the ambulance turned off its lights.

“Anyway, somebody had better watch out,” Davey yells, wiping his eyes. He shakes his head. “I don’t even know you people—not really—it could be any of you—and if you’re in here”—his eyes blaze—“if you had the guts to stuff my sister and show up today . . . just know that I am more than willing to go to prison for the things I would do to you—”

“Jesus, Davey!” Mrs. Fried shrieks. She stumbles into the aisle, and Mr. Fried shakes his head and struggles after her. Davey just stands up at the microphone, staring out at us, looking confused. I try to start a slow clap, but nobody joins in. I’m thinking about how maybe I should slink out, too—jump into the Subaru with Dom and ditch. But it would be even ruder to not go to the wake. And for some reason I figure I should stick around and grab our baking tray from underneath the cookies. For some reason, that’s what I am focusing on.

Davey was right about one thing: everyone’s a stranger now. Feeling safe is a hard habit to break in Friendship, but now that it’s broken, I don’t think people will trust each other for a while. Our neighborhood is the kind of place where lots of people have one another’s keys. Most of the time, no one around here locks anything, except maybe their gun cabinets. But after the murder and the hubbub and the roped-off cornfield, you could hear doors clicking shut down our street like dominoes. When Dom and I went home to bake the cookies, I saw some neighbors taking out their trash, and they were all sort of eyeing one another across the fence—looking antsy and going about their business in a quiet kind of hustle, like something was chasing them.

The reception is being held down the block at the community center, which is usually used for school dances. I am standing in the corner, by the window, where during homecoming I waited for Ruth and Colt to be done slow dancing so I could do “the awkward turtle,” which is what Ruth called my only ever dance move. Now I’m watching my cookies disappear one by one off Dom’s tray. The room is filled with the sound of soft condolences and chewing. People mill around, carrying tiny plates full of casserole, meat loaf, or cookies—occasionally stuffing their faces, occasionally ducking down to talk to Mr. and Mrs. Fried, who are sitting on a sofa in the opposite corner. Everyone’s eyes are red. Dom is by the bubbler, refilling Mrs. Fried’s glass. I feel like I’m underwater.

“So,” I say quietly, and then look around for someone I can pretend I’ve said it to.

Davey is a few feet away from me, nibbling on the rim of a Styrofoam cup. He keeps glancing nervously at his parents. I stare closely at his bandage for the first time, and realize with a twitch that one of his fingers is missing. The dressing there is reinforced and tinted pink.

“What the heck happened?” I blurt, stepping toward him.

Davey startles. “What?” He follows my gaze. “I don’t know, Kippy, things happen.” His voice is garbled. He spits a piece of Styrofoam into his cup. “In this case, the military happened.”

“Sorry.”

“It’s not your fault,” he says.

But it is, I think. Not his hand, but what if I’d called earlier and Ruth was still alive? And then something even more terrifying hits: What if I keep asking myself that question for the rest of my life?

I notice that people are starting to hold my cookies up in front of their faces, looking all perplexed, and that some of them are actually hacking—hawking chewed-up cookie back into their hands. I realize that maybe I accidentally used salt instead of sugar. I was barely paying attention because I was too busy watching this Diane Sawyer report on dog weddings (weddings between dogs). I push past Davey and start tearing cookies out of people’s hands.

“Cut it out,” I am saying, filling my arms with cookies, dropping some onto the carpet. My heart is hopscotching in my chest. “Give me that.” I stumble to the trash can and chuck the armful into the bin. The conversation stops and people hold their meat loaf slices more protectively. Mr. and Mrs. Fried peer at me from the couch. I grab Dom’s tray and tip the remaining cookies into the garbage. I am covered in crumbs. I scan the room and people look afraid of me, except for Dom, who quickly puts down Mrs. Fried’s drink and hurries toward me, his face all loving and concerned. My eyes burn because I don’t want him to be nice, and suddenly the funeral guests turn to liquid. The air around me vibrates. “I’m really sorry about everything,” I say to the shapes of Mr. and Mrs. Fried. “Like about Ruth, and how I messed up everything I needed to do today.”

Dom’s arms are already around me, but I shrug him off and run out of the room, out of the building, into the cool, autumn air and toward the parking lot, the metal cookie tray popping in the wind.

Ruth and I thought it was weird our parents were Republicans. Our plan was to save the world by saving gas, so we decided to hoof it as much as possible until it got too cold. After all, our neighborhoods were only ten minutes apart.

But then Mrs. Fried said we could only walk the stretch of Route 51 at night if we wore special reflective gear, so that the occasional car or truck could tell us from shadows and we wouldn’t get hit—which meant that every time Ruth came over, she had on this ultra-intense crossing-guard regalia: a neon yellow vest that took batteries and flashed orange and red when you walked. She and I called the vests Grab Me Garb, because they made us look like bait.

Ruth was always the brave one. The squirrels in my yard would hang out like they owned the place, squatting on their fat butts, eating an acorn, or whatever, like it was corn on the cob. I always told her they probably had rabies, but Ruth would hiss at them—like, get really close and hiss right in their face. Once, she snuck up and grabbed one, and while it arched its back and flailed around trying to bite her, she went into one of those shot put spins and sent it sailing into the trees.

Before Davey gave his speech, I had this really distinct picture in my head. That she kicked, fought, swore. That whoever did it left the cornfield beaten and bruised from the fight. And now all I can think about is how it wasn’t like that at all. How maybe she even tried to run away, her heart suddenly chicken, forgetting entirely that she was lit up like a Christmas tree.

I hear Dom chasing after me, but I just speed up, making a beeline across the parking lot, heading for the car.

“The cookies were bad,” I shout over my shoulder, throwing open the back door and shoving the pan inside. I am hiccupping. I am ugly with tears.

Dom trots up behind me. I struggle under his hug, but he holds me tight. “Hey . . . hey,” he says softly. “Let’s stop a sec, okay?”

“But the cookies . . .” I dissolve into involuntary groans and hiccups. Tears and snot are like glue across my face.

“It doesn’t have to be about the cookies,” he says. “It’s okay to be upset about what you’re upset about.” He leans back and looks at me, still holding on. “As someone who also appreciated Ruth as a person, I can only imagine how hard this is for you.”

“Yeah, but that’s not the point,” I plead. I’m thinking about how I will have no one to stand with in the hallways. How part of me wishes she would come back and the other half doesn’t even know if she liked me.

“I’m a bad friend,” I finally say. “The cookies were bad and I was bad. I was really, really bad.” I stare at the ground, brushing Dom’s hand away as he tries to wipe my cheeks with the sleeve of his sweater.

“My little porcupine,” Dom says softly. “There are different kinds of bad.”

“Oh, just quit it with the psychobabble,” I snap and shove him off me. I barrel into the car and slam the door.

I watch Dom sigh and go around to the driver’s side. The minute he gets in, I yell at him again. “I’m not going to revel in this with you, okay?”

Yet as we drive back, I am relieved by this sadness creeping in. Fall used to be my favorite season. All that happy red, bright and scattered everywhere. Now I look around and all I see is death, moving across the leaves like a fire.

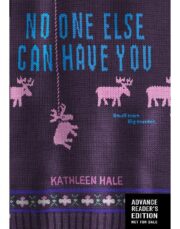

"No One Else Can Have You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No One Else Can Have You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No One Else Can Have You" друзьям в соцсетях.