“So,” I say, flicking the glitter off my lap in Staake’s direction. “Tell me: When you were coming last night, was it to arrest me or rescue me?” I wasn’t planning to torture him like this, but now that I’ve got him here it’s kind of hard not to. He looks miserable. “Because that’d be an interesting thing to add to whatever apology you were planning for the press.”

“Oh, Bushman,” he says, burying his face in his fingers. He folds his hands in his lap and his mouth quivers as he looks up at my leg. “I can’t believe how hurt you got.”

I can tell he’s thinking about how he’d feel if I were his daughter, Lisa, and he looks so much like a dad all of a sudden that I get uncomfortable.

“Um—well, you know, it can’t be helped, or whatever.” I push a strip of loose gauze out of my eyes, and gesticulate as if this situation is not a big deal.

He looks at his feet, sighing through his nose, and I get frantic.

“Don’t cry, please.”

“I want you to know I’m gonna give a press conference,” he says, swallowing. “I’m gonna own up to what happened, but I’m gonna tell it my way. I got swindled by that freak, I did.”

“I know you did,” I say. “But you were also a jerk.”

“Well sure, fine, but that’s how I am.” He looks at me sort of helplessly. “But I sure wish I could be that kind of person other people thought was nice.”

“Okay, Mr. Staake.”

“You can call me Bob.” He wipes his eyes, then holds out his hand.

I shake it. “Bob,” I say.

I’m going to give Ruth’s diary to Davey when he comes back. It’s all crumpled from being in my backpack while I was getting dragged around and pummeled. But I can’t look at it anymore. And I figure I’ve struggled through enough of it now to say you’re never really ready to read a dead person’s thoughts, not if you loved them and cared what they thought to begin with. If I held on to that journal, I might never be able to put it down. I’d reread the hurtful stuff and cling to the few positive passages, and try to analyze how real things were between us, even though I know people probably only talk about the bad things in their diaries, because what’s the use of recording what you don’t have to work through? And I’d rather give it up while I feel like I know that things between Ruth and I were good, basically, solid—and that ultimately she’d appreciate me sticking it to the bad guy, and for being even momentarily badass in her honor.

On the inside cover, below all the phone numbers and psychopathic traits, I left a message for Mrs. Fried:

Mrs. F—

Proceed with caution because I couldn’t get rid of all the sex parts.

I’d like to tell her I’m sorry about the eulogy, and that I understand why she can’t see me, though I still wish she would. But I know it’s not worth worrying about because right now I’ve got more company than I can deal with. Dom, Miss Rosa, and the rest of NVCG are filing into the room, Davey will be back soon, and the hospital phone by my bed has started ringing off the hook—newspaper reporters and third cousins I’ve never heard of, Principal Hannycack and some Wisconsin senator. Even Diane Sawyer’s office calls, asking about an interview. Mildred thinks the phone number got posted online, or something, and Marion starts screening all the calls for me, telling people to call back, jotting messages, telling crazies to feck off. But at one point he holds out the receiver and says, “This one’s funny, just a kid or something, listen,” and it’s Albus.

“Good job, soldier,” she chirps. “I taught you well—oh, shoot, gotta go—it’s the Barb and Felicity brigade—over and out—aggh! Unhand me, nurse warriors!”

It still hurts to smile, but really it’s kind of hard not to, because I thought that I only had one friend in the whole world, and look at all these people.

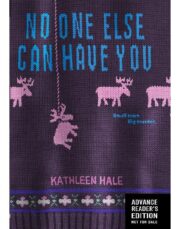

"No One Else Can Have You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No One Else Can Have You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No One Else Can Have You" друзьям в соцсетях.