“It’s Kippy,” I say, and hear the words vibrate dully against her sternum.

“We’re all so worried about you,” she says, shoving me off her. One of the girls hands me my cookies back and the whole group smiles in unison. Before I know it, they’re all skittering off in their high heels, looking around to see who else is coming inside.

“Thank you?” I call after them.

Friendship is small enough that you can all sort of recognize one another. But so far I don’t think most of these people knew Ruth. Not really, anyway. It was the same at my mom’s funeral. Lots more people came than we actually knew. Dom called them Grief Gawkers. Still, it wasn’t this crowded. I mean, Ruth was popular by association, but nobody has this many fake friends.

So far I don’t even see Colt, but he’s probably around somewhere, unless he was too sad to come. Sheriff Staake (pronounced Steak-y) usually makes a point of coming to important town events, but he must be out prowling for the killer, or standing watch like Dom, because there aren’t any cop cars in the parking lot. Friendship police vehicles are pretty conspicuous. They have big yellow smiley faces on the sides. The sheriff’s car is different because the smiley face has sunglasses on it.

I wiggle and weave through the hordes, still holding the tray of cookies above my head. “Sorry,” I’m saying. “Excuse me, I’m doing the eulogy, sorry.” After a while the crowd becomes a single-file line. I stand on my tiptoes and see Ruth’s family, all lined up and letting people grab on to them and kiss their heads. Davey’s with them, Ruth’s big brother. I haven’t seen him since freshman year of high school. He never came back to Friendship after he was deployed. I guess the army gave him leave or something for the tragedy. He was special ops. My neighbor Ralph said that means he’s trained to kill.

Davey sees me squeezing past these strangers and breaks away from greeting people to walk toward me. When he graduated high school he was all skinny, but now he looks like he could lift a truck. I notice he’s got a pretty heavy-duty bandage on his right hand.

“Kippy Bushman,” he says, taking the cookies from me. A buzz cut looks good on him. “How are you?”

I feel like I should know the answer to this by now, but I shrug. Davey’s face is wet, either from crying or people’s sloppy kisses. I look again at his hand. This morning I watched a Diane Sawyer interview where there wasn’t one awkward pause. The trick is to pose good questions.

“So how was being in the war?” I ask.

I’m always saying the wrong thing.

“Is this thing on?” I hold the podium with one hand and tap the microphone with the other. Someone has finally turned off the dance club music, and Rob is going around the room, cranking open all the windows. Davey brings his thumb and index finger together and signals “okay” from his lap. According to the pamphlet they gave me at the door, he’s next up on the eulogy schedule.

“Hi,” I say slowly. My voice echoes in the small room. I glance at my backpack, which is still on my seat and has Ruth’s diary in it. I don’t know why I even brought the journal. Staring at it across the room is not helping me think of what to say.

“Or as they say in France, bonjour,” I add.

I’m not very good at these things. Last semester I gave an improvised speech in debate class and threw up in my mouth. I look out at the audience and swallow, reaching instinctively for my necklace. It’s half a heart, and touching it used to calm me down because Ruth was supposed to have the other half. She said it was the gayest thing we’d ever done, but I always thought she wore it. Only when Dom said it was okay to ask Mrs. Fried for Ruth’s other half, Mrs. Fried said they didn’t have it, so apparently Ruth wasn’t wearing it when she died. Maybe she lost it and just never told me because she didn’t care. Or Jim Steele told her it was stupid and the two of them smashed it with a hammer or something while laughing about how pathetic I was.

I crumple the hem of my cardigan in my fist and chew on the edge of my tongue. My face is hot and probably bright red. I suddenly remember the feeling of climbing back down the ladder of a diving board in front of a long line of other kids. I have to at least try.

I take a deep breath and jump in. “What can one say about friendship? That is the question.” I spread my arms like some kind of preacher and look out at the Frieds, who are saving my seat in the front row. They stare back at me. Maybe if I hold this pose long enough, and let the question sit, someone in the crowd will actually answer it—for a moment I even see myself leading a call-and-response thing like on the evangelical channel. But the room stays quiet, and within a few seconds there’s a sour taste in my mouth. I lower my hands, drum my fingers on the podium. Someone in the audience coughs.

“Well, Friendship is our town, for one thing,” I blurt. “And everyone knows what our town motto is: ‘Do Unto,’ plain and simple—’Interpret that as you will,’ Principal Hannycack once said. Um.” Mrs. Fried forces a smile at me from the front row, and I feel sick.

“But friendship is also another thing,” I go on. “It’s a thing between friends, and you have it when you’re a friend to someone, and they’re friends to you, and the equation makes it so that you’re friends together, amen.” My face twitches. Did I just say “Amen”?

“Ruth was super-duper,” I announce. Super-duper? I swallow a few more times, fighting off the urge to barf. “In conclusion, friendship, the thing I’m describing, it was, well—Ruth and I had that until she was murdered—I mean. Holy geeze.” Wide eyes blink against black outfits. “Thank you and please make sure to try the sugar cookies I baked for this occasion.” I wave good-bye.

Ruth’s mom won’t look at me, and Mr. Fried’s face is twisted like he might scream. The microphone rings as I scuttle away from the podium. Libby Quinn and her posse whisper at each other in the doorway. “That was the best friend?” I hear someone say.

“A big thank-you to Kippy Bushman,” Davey says when it’s his turn, “for, um, trying her best.” He spreads his paper on the podium and goes into the stuff you’d expect, introducing himself, talking about his relationship with Ruth. The stuff normal people say.

“She had spunk,” he says. “Even as a kid, she could be crazy. One time she set up this elaborate system of trip wires around the house, and I fell on one and broke my teeth.” He laughs. “Dad made her point out the rest of them to us, but there were so many she couldn’t remember where she’d put them. Our whole family was falling down everywhere for about a week before we found every one.” His smile fades. “I think she felt bad about it.” There’s something weird about his voice, and all of a sudden I realize it’s that he doesn’t sound like his dad—that he’s lost all trace of a Wisconsin accent. Or maybe he never had one to begin with. Around here, the accents usually kick in toward the end of senior year, when people decide what they’re doing next, and whether or not they’re going to stay. Talking like you’re from here is a way of digging your heels in.

“You know what,” Davey shouts. “I’m with Kippy, I can’t handle this.” He wads up the piece of paper he’s reading from and throws it at the crowd. “What the fuck is this? What are you even supposed to say?” He bangs the podium. “Do you people know how Ruth died? No, you wouldn’t, would you, because everyone around here’s too damn nice and what happened is too unsuitable to talk about, am I right?”

The crowd is silent. Even Mr. and Mrs. Fried are sitting stock-still in their seats. He’s right. We’re too polite to shout at him to stop. It goes against everything in our town to share the nitty-gritty details of anything even vaguely private or graphic. All they would say on TV or in the papers was that it was bad, and “totally sicko” and “you don’t want to know.”

“They should call her killer the scarecrow murderer,” he says dully. “Because whoever did it tore apart the Schultz’s scarecrows. They crammed the straw into my sister’s mouth before sewing it closed.”

“Young man!” Across the aisle from me, an angry-looking grandpa type stands up, points a quivering finger at Davey, and starts to say something. But Davey pins him with a look, gripping the edges of the podium so hard that you can see his muscles through his dress shirt. The man sits down.

“Red thread,” Davey says, still staring down the man. “Her mouth was decorated like a baseball, do you hear me? Someone broke her teeth stuffing straw down her throat. Her neck was bulging from it. They even found pieces of straw in her stomach.”

I can hear the sound of fingernails on fabric beside me and turn to see Mrs. Fried gathering her husband’s coat sleeve in her fist. Her eyes are bulging.

“She was alive when it happened,” Davey says. “She probably had to watch her killer take out that needle and thread. They only dropped her from that tree branch after the fact—after she’d already suffocated on her own teeth and bile and straw. Then they did her like a buck from a basketball hoop.”

In Friendship, people go hunting, then tie up the kills by the hind legs and disembowel them so they can bleed out on the pavement. On the way over, I leaned against Dom’s passenger window and counted the number of dead bucks tied to people’s basketball hoops. I got to seven before we pulled into Cutter Funeral Home. My stomach lurches.

I grab Ruth’s diary, flipping through to the back. I can feel Mr. Fried giving me a warning look, but I ignore him. I can’t believe I didn’t think to check the entry for the day Ruth died. Maybe there’s something there that I can decipher without going letter by letter.

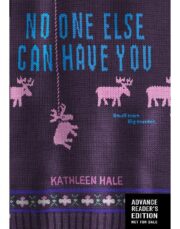

"No One Else Can Have You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No One Else Can Have You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No One Else Can Have You" друзьям в соцсетях.