“You will be ill,” scolded Guillemote. But she was the same. I knew how her thoughts ran, for they were similar to mine. Where was Owen? What was happening to him now?

We worried about the children. What could we tell them? Edmund and Jasper were too old not to know that something was wrong. Jacina knew too. They watched us with frightened eyes.

I could think of nothing but Owen…gone…taken by those wicked men. Should I ever see him again? I dared not think of that possibility. I could not bear to consider what my life would be without him. I was numb with misery.

I must do something. I must go to London. I must find him.

There was my son, Henry the King. He would help me. Bedford was dead. He was one who might have understood. How could I plead with Gloucester? I pictured him as I had last seen him. He had been so angry with me. Even then he must have been planning his revenge.

I must see Henry.

“Guillemote,” I said. “I am going to see my son. I am going to beg him to send Owen back to me.”

“How could you see him?”

“I will go to London…to Westminster…wherever he is. I will go to Court. I will explain.”

“You could not travel in your state. My dear, dear lady, think of the child you carry. You must not distress yourself so.”

“Oh, Guillemote, why do you talk thus? They have taken Owen. How can I help being distressed? I must see Henry.”

“You cannot travel.”

“I will write to him. I will ask him how they dare arrest Owen as though he had committed some crime. What has he done?”

“My lady, he has married you.”

“Why should he not? We love each other, do we not? What harm do we do?”

“It was against the law.”

“Gloucester’s law! In any case, we were married before that became law.”

“I know. I know. Write to the King. He loves you well. It may be that he will come to your aid.”

“He will. Of course he will. He is my own dear son.”

I could not gather my thoughts. My hands shook so that I found it difficult to hold a pen.

“Henry,” I wrote. “You must help me. They have taken Owen away. You must order them to send him back. You must save your mother, for surely I will die if Owen does not come back to me …”

That would not do. I must write clearly. I must explain. I did my duty for my country and for your country, Henry. I married the conqueror of France. I bore his child, you, my dear one, and now it is only just that I should know some happiness. Please, Henry, if you ever had any affection for me, help me now. You can. You are the King. You must remember that. You can command these wicked men to undo the evil they have done to me …”

There were sounds of arrival below. I dashed to the window, but I could see nothing.

Guillemote was running into the room.

“Guillemote, Guillemote, what is it?” I cried. “Owen has come back. Oh, tell me Owen has come back.”

“There are men to see you, my lady.”

“And Owen?”

She shook her head. “They are saying they must see you at once.”

“Oh, Guillemote, what now? What now?”

“I know not, my lady.”

“Where are the children?”

She nodded her head upward.

“What is it, Guillemote? What do they want?”

“They will tell you, my lady.”

I followed her down the stairs. They were standing there. Guards…like those who had taken Owen away.

“My lady …” they began and hesitated.

“What have you to say to me?” I asked dully.

“My lady, we have come to take you on the King’s orders to the Abbey of Bermondsey.”

“To Bermondsey? But…why…why should I go to Bermondsey?”

“You will be cared for there by the abbess, my lady. It is the King’s orders.”

“My son’s orders? I do not believe it.”

He unrolled a scroll of parchment and showed me Henry’s signature.

“I do not understand …” I began.

“The King’s orders are that you should be taken to the Abbey of Bermondsey and put into the care of the lady abbess there. We must leave within an hour.”

I said: “The children …”

“We have orders for them, my lady. They are to be put into the care of the Lady Katherine de la Pole, the Abbess of Barking.”

“But Barking is not Bermondsey!” I said foolishly. “I am to go to Bermondsey.”

“That is so, my lady. And we have to leave very soon.”

“I will not,” I said.

They looked at me sadly. “Our orders are to take you, my lady.”

I felt helpless, for they were implying that if I did not go willingly they would take me by force.

“Where is Owen Tudor?” I asked.

They looked at me blankly.

“The children should be made ready to leave,” said one of the guards. “You too, my lady.”

Guillemote was standing behind me. I turned. We just looked at each other. I had lost Owen. I was going to lose the children…and Guillemote, the Joannas, Agnes…and all those who had served me well…everything I cared for would be lost to me.

This was cruel. This was unbearable. How could anyone do this wicked thing!

It was no use pleading with these men. They were only obeying orders.

Guillemote took my arm, and together we went up the stairs.

So they took me to Bermondsey. I was numbed by bitter misery. I did not say goodbye to the children. I feared to frighten them. I cannot forget the memory of Guillemote’s white face, her eyes wide with pain as they dwelt on me. There was a sense of desolation about the entire household. Everyone now knew that the disaster which for so long we had feared had come upon us.

I cannot remember very much of the journey. The abbess received me with deference. Her prisoner I might be, but I was still the Queen. My room was simple—bare walls except for a crucifix. I hardly noticed. Two nuns came in and helped me to bed. I lay in those unfamiliar surroundings, staring before me, seeing Owen walking across the grass between the guards…Guillemote hustling the children away.

They tried to make me eat, but I could not.

The hours passed. Night came. I did not sleep. I just lay there in that austere bed wanting to die.

The abbess was a kindly woman. She was concerned about me and tried to make me talk.

“You must find peace,” she said.

“There is no peace for me,” I replied.

“God will help you.”

I was impatient. “All I want is my husband and my children.”

She was indeed a good woman. I saw compassion in her face.

“Would you not pray with me?” she asked.

I turned my face to the wall.

“I want to help you,” she said.

“Then give me back my husband and children. That is all I want. The right to live as the humblest woman is allowed to…the right to be with my family.”

She left me in despair.

Another day. Another night.

“You must rouse yourself,” said the abbess. “You will lose your reason if you continue thus.”

Lose my reason! Her words had sent me back to the Hôtel de St.-Paul. I was hearing that wild voice calling for help. I was seeing my son bemused by the sight of The Maid. The abbess had reminded me of the shadow which hung over my family.

Be calm, I said to myself. Think of other things.

But I could think only of Owen and the children around us…a bright sunny day…and such happiness suddenly shattered by the sound of horses’ hoofs coming toward the house.

I was alone. The abbess had left me in despair.

I started to think back over the years of my childhood, to my first meeting with Henry, to my life with him…the birth of my son. They were not unhappy days. But it was only when I knew Owen that I discovered what true happiness was. Few people find it as Owen and I had. What a tragedy that we should have had to hold it so carefully until it was finally snatched from us.

The words of the abbess kept coming back to me. “You will lose your reason.” There were times when I was not sure whether I was in the past or the present. Sometimes in the night I would think I was in the Hôtel de St.-Paul, lying close to Michelle for warmth while Marie prayed at the bedside. I thought: I must be calm.

The idea came to me that the only way in which I could live through the days was by writing it all down. Perhaps I should discover where I might have acted differently. Could this have been avoided? Was there a way in which Owen and I could have been together and there was no cruel parting? Was it just possible?

It was true that I felt better. The abbess was pleased that I had this occupation. She could see that it helped me.

Writing materials were supplied to me, and through the days I wrote. I became fascinated by the project, I think largely because for hours at a time I could lose myself in the past and shut out the desolate present.

The summer had gone. I had no knowledge of what was happening to my family. I was sleeping a little better now…I did not dread the long nights as I had, for, having written of the past and in a manner lived it again, I felt a certain exhaustion at the end of the day which I welcomed.

I would sometimes dream that I was happy again, that Edmund, Jasper or little Jacina was telling me what they had done that day, that little Owen was talking to me, in his quaint baby way. I cherished those dreams, for they brought a fleeting happiness into my dreary existence.

It must be nearly Christmastime. I was trying not to think of last Christmas. I had covered so much paper with my writing. I was getting near the end. It was almost unbearable now because I was writing about my life with Owen and the children, and all kinds of little incidents came to my mind…too trivial to record but precious to me.

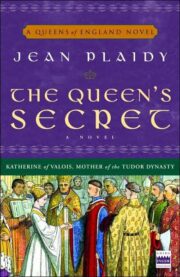

"The Queen’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.