Could it be possible that they had met as Gloucester was leaving the house?

Guillemote brought the children to me. Edmund and Jasper scampered across the room, Jacina toddling after them. They threw themselves into my arms. I held them so tightly that they protested and wriggled free. I was trying to stifle the terrible fear in my heart. I gazed over their heads at Guillemote. She was standing still, holding the baby, and I knew by the expression on her face that she had met Gloucester.

The children were all talking at once, telling me about their journey…how Edmund had ridden with Jack on his horse, and Jasper with Dick. Jacina had been in the litter with Guillemote and the two babies—Daisy’s, who was the wet nurse, and little Owen. I feigned an interest but all the time was wondering what had happened.

They had gone to the big house, Edmund told me. They had all slept together…except the babies. They had played in the gardens.

I knew that Guillemote was longing to talk to me, but by tacit agreement nothing was said until the children had gone to the nursery.

Owen was with me. He had been in the gardens, had seen Gloucester’s arrival and had thought it wise to keep out of sight. Then she had seen his departure after the brief visit and had been about to come to me when Guillemote had arrived with the children.

“I was horrified,” he said. “It seemed certain that they had met.”

Guillemote explained to us.

“We were turning into the palace when he came riding along with his small company. I was in the litter with little Owen and Jacina and the wet nurse and her child. Edmund and Jasper were riding with two of the men. I recognized the Duke at once and I was very shaken. We could not turn back. We were too close for that and he had already seen us. We had to pass each other.”

“What did he do?”

“He drew to one side of the road…signing for his men to do the same. They stopped. He lifted his hat and bowed his head. He seemed to be staring at us all. I was not sure whether he knew who I was. He would probably know some of the ladies. I thought it hardly likely that he would have noticed me from the past when he may have seen me once or twice. He looked at the children and…we passed on. The way he was looking at us sent shivers down my spine.”

“Is that all?” I asked.

She nodded.

I looked at Owen. It was enough, we both knew.

We were certain that Gloucester would take revenge. The only thing we were unsure of was when; but we believed it was only a matter of waiting.

He had always had the notion that, in view of my position, I must be watched. He had been determined that I should not marry again. I had been wife to the King, and he probably thought that any children I might have could imagine they had pretensions to the throne. It was hardly likely, of course, but a man such as Gloucester would be alert for possibilities.

My son was King; it was likely that he would marry and have undisputed heirs to the throne. But strange things happened in the royal line. And at the moment between Gloucester and what he coveted there was Henry and after Henry, Bedford. And Bedford had no heirs. I believed Gloucester had not worried a great deal about my activities in the past—but certainly enough to try to prevent my marrying again. Yet I had been a mild irritation until now. The King was growing up, and it might be that my influence over him might increase. And now I had openly offended Gloucester. He believed I had turned my son from falling in with his wishes. Gloucester was a man who did not like to be flouted. He would regard what I had done as an insult—and insults must be avenged.

I guessed, therefore, that sooner or later he would strike, and I am sure the blow would have come more quickly but for a dramatic turn of events.

The French were heartily tired of the war. I supposed the English were, too. No one was winning. If Henry had lived, people were saying, the conquest would have been completed by now. France and England would be one country under the domination of the English. But what was the case now? True, the King of England had been crowned King of France. Who was to say which was the King? What was the point of paying taxes just to continue a war which was coming to no satisfactory end? It was different before the coming of The Maid. Truly, she had changed everything, and although she had not brought complete victory to the French, she had made the English position very difficult to hold…and it was becoming more so.

At this time there was a meeting in Arras which must be causing a great deal of anxiety to the Duke of Bedford. I thought of him as I had last seen him, his face careworn and a desperate sadness in his eyes…in fact, a certain hopelessness.

The meeting in Arras was an attempt to bring an end to the war and to unite the royal house of France with that of Burgundy. If this succeeded, it would be a fatal blow to English hopes in France.

Looking back over the events of the past years, I could see what an effect that quarrel had had on our history. The Duke of Burgundy and my brother Charles were both Frenchmen—moreover close kinsmen—and the quarrel of the Orléans–Armagnac faction with Burgundy had been the downfall of France. It was not until a simple peasant girl had restored that country’s faith in itself that the misery of failure and defeat began to lift.

It was quite clear that Philip of Burgundy and my brother Charles must become allies so that France could grow proud and strong again.

It was tragic that the two leading houses in France should be fighting against each other when an enemy was attacking the country. There must be an end to this talk of revenge. The welfare of France must come before petty family quarrels. Frenchmen must not make war on each other.

The English refused to give up their claim to the crown of France, and Bedford left Arras and went to Rouen. I could imagine his thoughts as he entered the town. This was the place where they had burned The Maid, but she was indestructible. They may have destroyed her body, but her spirit lived on.

I remembered Tressart’s words: “We are lost. We have burned a saint.”

It might well be that he was right.

And there in Rouen, that city of bitter memories, Bedford would be awaiting the outcome of the meeting at Arras. His relationship with Burgundy had suffered even further since the death of Anne. It was she who had helped keep it alive. Bedford had respected Burgundy, and Burgundy had respected him. They had been brothers-in-law. And then Bedford had married again, and so soon after Anne’s death. True, there was an advantage in the match, but it had surprised me…and no doubt others. Moreover, the marriage had naturally displeased Burgundy and could only be expected to widen the rift between them. Perhaps Bedford realized during those days in Rouen that his marriage had been a mistake, for it was still of the utmost importance to England to keep on friendly terms with Burgundy—far more important than any advantage which could be obtained elsewhere.

I had always admired Bedford. He was undoubtedly the best and most honorable of Henry’s brothers. He had been a good friend to me and a good guardian to my son.

When I heard that he had died in Rouen, I was overcome with grief and a sense of foreboding.

The first thought that occurred to me was: the Duke of Gloucester is next in line to the throne.

We had waited in trepidation for some reaction to his discovery. I was sure he had heard rumors about my relationship with Owen, for, careful as we were, some little indication must have leaked out. There was that occasion at the dance when he had fallen into my lap. That had happened a long time ago, but at the time I was sure it had been talked of. Sometimes such things are greatly exaggerated and a minor incident is turned into one of significance.

After he had forced the statute through Parliament about my remarrying, Gloucester had done nothing. That might well have been because he had matters of more significance to occupy him. But now that I had presumed to advise the King, I had brought myself to his notice, and I was sure he would have taken some action if it had not been for his brother’s unexpected death which had taken him a step closer to the throne; and he would have thought for nothing else at this time.

Later I heard accounts of how the Duke of Bedford had died. He was a sick and disappointed man, obsessed by the fear that he had failed in the mission his brother had left to him. He had gone wrong somewhere, he was convinced. He should never have allowed them to burn The Maid at the stake. It was said that that—and much else—was on his mind when he died.

He had been disturbed by the effect The Maid was having on the war, and he had felt at the time that she must die. But then he began to wonder whether he had offended Heaven and whether, even from a practical standpoint, it would have been better to have let her live.

I was sorry for him. He had been a good man, kindly if stern. He had always tried to do what he considered right, and what more can a man do?

He lacked Henry’s genius, but who did not? Events were too much for him. It was tragic that such a good man should die disappointed.

His death was the final break with Burgundy. It was timely, too. It really seemed as though God’s hand was against the English, for it happened just at the time of the Treaty of Arras and must have decided Burgundy.

There was no Englishman whom Burgundy trusted as he had trusted Bedford. So he had made his decision. Frenchman would not fight Frenchman again.

We heard of the rejoicing throughout France. People were dancing in the streets. Burgundians shook the hands of the Orléans-Armagnacs. They drank together. They vowed never to fight each other again. The only cause for which they would fight would be that of France.

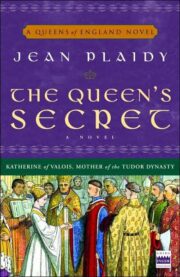

"The Queen’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.