The Duke of Burgundy had signed the Treaty of Arras.

“Long live Charles the King!” shouted the people. “Long live the Duke of Burgundy!”

I believed that England’s hopes in France were doomed from that day.

But my main thought was: Gloucester is now next in line to the throne. If Henry were not there, he would be King.

Paris was about to be taken back by the French. The English were leaving; and in the midst of this turmoil, my mother died.

I cannot believe that she was sorry to go. Her life must have changed drastically. She was old and fat and full of gout, and to a woman who had used her beauty and set such store by it, using it to satisfy her ambitions, old age must have been hard to bear.

I wondered what she felt on her deathbed when she was about to leave the world which had meant so much to her. She must have known that the English were preparing to leave Paris and that her son’s triumphant army would soon be in possession of the capital. And what did she think Charles would say to her? She had scarcely been a friend to him, and certainly not a good mother.

He had been at one time beset by doubts as to his legitimacy. It was Joan of Arc who had convinced him that he was the King. His mother had sided with his enemies…against him. She had been responsible for so much misery that had befallen his country; and his mother-in-law, Yolande of Aragon, had shown him what a mother could be.

He would hate his own mother. Would he show any mercy to her now?

That was something we should never know, for she died before the English left.

They showed a certain respect for the dead. They had her body laid in a coffin which was placed in a barge and carried down the river to the Abbey of St.-Dénis, where she could be buried among the kings and queens of France.

So there were two deaths in one short month.

“Gloucester will have other matters with which to concern himself now,” repeated Owen.

From the peace of Hadham, Owen and I kept an eye on what was going on.

The death of Bedford, we assured each other, had made such a change in Gloucester’s prospects that he had almost certainly turned his attention from us. We began to settle into our peaceful life once more.

Looking back now, I feel that we seized those days with great eagerness because we felt we had to live each one to the full, being fearful of what disaster could come upon us at any moment.

The quarrels between the Cardinal and Gloucester persisted. Now that Burgundy and the King of France were allies, the English cause in France seemed hopeless, and the Cardinal wanted to explore plans for bringing about peace.

Gloucester was of a different opinion. He declared that there had been mismanagement. All we needed was a return to the methods of his brother, and we should be successful again. He was the man, he tried to assure the country. But although he was cheered in the streets, for his great asset was his charm and a certain bonhomie which he could produce at a moment’s notice, no one really thought he could attain the victories which had come to Henry.

Owen said: “We should be thankful that he is so occupied. It is certain that, in the midst of all this, he can give no thought to our little matter.”

The Cardinal thought that Henry should make a marriage with the eldest daughter of my brother Charles. He got so far as putting the suggestion before the French. To my relief, they treated it with an indifference which infuriated the English. I could not help thinking of my father, whose madness many believed had come to him through his mother. That was what had made me fearful that it might have been passed on to Henry. But I had consoled myself that it was only when he had been disturbed by The Maid that I fancied I had seen signs of instability. But everyone had been affected by The Maid. And what of Charles? He had always been rather odd…and his daughter…what of her? They were only faintly uneasy thoughts which came to me, but I was glad when the match was put aside.

Then Gloucester went to France, and we settled down to peace. And during that period of peace I became pregnant again.

Once more I settled into that state of contented serenity. I often wondered afterward how I could have shut my eyes to all that was happening about us; but I did. When I look back, I can see that some of the happiest times of my life were when I was expecting a child, because then I seemed able to forget all fear of what trouble might be brewing for Owen and me.

We heard items of news. The English were doing badly. They were somewhat demoralized by the loss of Paris. Calais had been assailed, and that was one of the reasons why Gloucester had left England to rush to its defense. To the English, Calais was the most important port. It was the gateway to France.

Gloucester suffered a blow to his vanity because Edmund Beaufort, nephew of the Cardinal, saved Calais before he arrived. I could imagine his chagrin. It would make him feel even more venomous toward the Cardinal.

I laughed about it with Owen, but my main thoughts were with the coming child.

Then Gloucester came back to England.

BERMONDSEY ABBEY

It was a hot summer’s day. We were in the gardens.

Owen was toddling now; the two elder boys were running about, playing some mysterious game, and as usual Jacina was trying to share in it and they were somewhat reluctant to allow her to.

I was early enough in my pregnancy not to feel unwieldy and I sat back enjoying the fresh air and the contentment of having my family about me.

Suddenly the silence was broken by the sound of horses’ hoofs. I started up. Owen had risen. Guillemote came running toward us. She gathered the children together and was murmuring that she had something to show them and they must come with her at once.

Owen and I exchanged glances. We were always prepared for unexpected arrivals. We had planned for such an event many times. He turned and went toward the stables. Guillemote was hurrying the children into the house, and I followed.

I was surprised. Important visitors usually notified us of their imminent arrival. This, therefore, could not be anyone of standing; however, we must be prepared.

I stood at the window watching. The Joannas and Agnes had come to stand beside me.

We saw about twenty guards below. They swarmed across the gardens. One of them had taken hold of a stable lad and was obviously questioning him.

My heart leaped in terror. The boy pointed to the stables. That was where Owen had gone. Two of the men had taken their stand by the door of the house, one on either side. The others were making for the stables.

Then I saw a sight which terrified me. The men came out of the stables, and Owen was with them. He glanced up at the house.

I could no longer restrain myself. I ran down the stairs and out through the door. The two guards standing there were startled. They stepped forward.

“I am the Queen,” I cried. “Stand aside.”

They let me pass. I suppose they knew I could not get far, and in any case, the rest of them were straight ahead with Owen.

I went to them. “What is this?” I cried. “What are you doing in my house…in my gardens? Do you know who I am?”

The men bowed. “We have orders to arrest this man,” said their leader.

“Whose orders? How dare you! He belongs to my household.”

“He is the Welshman, Owen Tudor. He does not deny it.”

“Why should he deny it? Release him at once and go. Go, I say! You will hear more of this.”

“Begging your pardon, my lady, we have been sent here to arrest this man, and that we must do.”

“Go away…go away. On what grounds? How dare you!”

“On the grounds of treason, my lady. Treason against the laws of the land.”

“Owen!” I cried and ran to him.

The agony in his face was terrible to see. He was shaking his head, warning me. I could see his fear for me in his face; and I thought I should die of anguish.

“Where are you taking him?” I asked.

“To London, my lady. Those are our orders.”

“Why? Why?”

“Orders, my lady. We are sorry, but it is our duty and we must obey.”

He moved toward me but they held him back, and for a few moments we stood there, just looking at each other.

I saw his lips move: “Katherine…my love…always my love …”

“I will not allow …” I began.

He smiled at me tenderly, resignedly. “I will be back,” he murmured.

“They have nothing…nothing…of which they can accuse you.”

“No…no,” he soothed. “It is a mistake.”

But we both knew that it was not. Gloucester was back in England. This was his doing.

So often we had thought of something like this happening; we should have been prepared for it. We were in a way, but perhaps we had always deluded ourselves that it would never come. But we could not have imagined misery such as this.

I was almost fainting. I was aware of Guillemote and Agnes. They were holding my arms. I could only cry out: “No! No!”

And it seemed as though from a long way off I heard the sound of horses’ hoofs as they rode away, taking Owen with them.

· · ·

I do not know how I lived through the days which followed. At every sound I would start up, telling myself that Owen had come back, trying to delude myself that I had been living in a nightmare of horror conjured up by my imagination. We had feared it; we had planned for it; and because of that I had thought it had really happened.

I could not eat; I could not sleep.

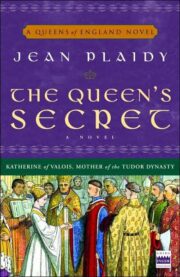

"The Queen’s Secret" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Secret". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Secret" друзьям в соцсетях.