In a place where no one else seemed to understand anything except how to gut a buck and go to church and be over-the-top nice without ever really bonding, Ruth and I made each other feel less lonely.

But that’s not the sort of thing I should write in my eulogy. Especially when everyone I’m talking to will be from the town I’m badmouthing.

I can hear Dom rustling around on the other side of the door. “Honey, Mrs. Fried’s on her way over,” he shouts pleasantly. “Finish up in there and let’s skedaddle.”

“Finish up what?” I call, wiping back tears. I want to hear Dom, who’s a trained psychologist, try to describe what exactly I’m doing in here. The way he talks, you’d think I was constipated or something.

“Sweetie, she’ll be here any minute, she’s imminent,” he pleads, and his voice is muffled in that way where I know his ear is probably pressed against the door. “It’s time to pull yourself together in bits and bobs and change out of those pajamas, okay?”

I roll my eyes. “Fine, but you have to promise you won’t make her do a trust fall or something.” Dom works as a counselor at the middle school, and is prone to some pretty touchy-feely suggestions in times of crisis.

“All right, Pickle. I promise. Can I get you anything?”

I want Ruth. As soon as I think of her, it’s like there’s a bird trapped in my chest—a vulture clawing my lungs and reaching its beak into my throat.

I can’t remember if it was like this the last time someone died on me. For some reason I didn’t expect it to physically hurt. But the pain is enough to make me want to call 911 and be like, “Listen, I have an emergency: Is this a broken heart or a heart attack?”

“I’m fine,” I say.

Ruth already got buried because of Jewish tradition. But the memorial service is tonight and Mrs. Fried is stopping by beforehand for some reason. I have no idea what she wants.

She and Dom must have spoken because she never called me. I haven’t heard from her since she texted me asking if I’d write Ruth’s eulogy. I wrote back right away saying that of course I’d do it—not thinking about how hard it might be to actually start. Now I’m supposed to address an entire crowd in just a few hours, and I haven’t written down a single thing. I keep trying and none of it is good enough.

I mean, Ruth was beautiful in a way that made you want to touch her face—she had dark, thick, curly hair, and nice skin, and big brown eyes—but that wasn’t who she was. Ruth Fried was easily annoyed by fakeness and she wasn’t afraid of feelings. She was the only person I’ve ever met who could make me feel better about losing control—encouraged it, even.

“That’s it, Kippy Bushman, get riled!” she’d say.

Or if I was all frazzled, about to cry because I wanted so badly to do well and not everything was perfect, she’d elbow me gently and say, “Listen, I think you just feel things more deeply than most people.” She could make me feel okay about basically anything.

I read in one of Dom’s psychobabble books that they can’t diagnose anyone under the age of eighteen with a mood disorder, because apparently teenagers are so selfish that no matter what it will seem like they’ve got one. And I understand that now because no matter how hard I try to write a eulogy for Ruth, I can’t come up with anything that is just about her, and not about how much I miss her.

Mrs. Fried walks in wearing all black and carrying a shoe box, and I’m so shocked at the sight of her that I start looking around the room to distract myself. Stressing about what Dom has done to our motel room is somehow easier than taking in Mrs. Fried’s unwashed hair and shaking hands.

Basically Dom covered the bedroom mirror with a bunch of towels and put a T-shirt over the one in the bathroom “just in case.” He’d read somewhere that Jewish people do that when someone dies. I didn’t know much about it, but I figured he was bastardizing some tradition, and tried to coax him out of it by telling him he was being totally weird and embarrassing, which, per usual, did nothing to stop him.

“It’s called sitting shiva,” he told me. “That’s what Mrs. Fried is doing at her house and I feel like it’s only respectful that we recognize her family’s customs.”

“Just because she’s sitting shiva doesn’t mean she has to take shiva with her everywhere,” I begged.

“Oh, Chompers—just simmer, okay?” Dom smiled sadly at me and went back to futzing with the mirror. Dom has lots of names for me: Pickle, Chompers, Cactus. Sometimes if he’s trying to be funny he’ll call me Pimple or Chocolate Butt, which is only okay because I’m acne-free and thin. Not to brag. I mean, things aren’t so great that I’ve ever gotten asked to a dance or anything.

“Well at least don’t use my bra to cover up the corner like that,” I mumbled.

“Maybe don’t leave your bras all over the floor,” he said, and used a sock instead.

Anyway, it doesn’t matter, because Mrs. Fried doesn’t notice any of it. She shows up clutching a shoebox, her gaze peeled on her hands. But even though she won’t look at me, I can see her eyes are so bruised and burnt from crying it looks like she’s been hit in the face with a baseball bat.

“Dominic Bushman,” she says softly, glancing at Dom. Ruth used to tell me her parents thought it was strange how when we were little everyone else was calling their parents Mommy and Daddy, and I had Dommy. I guess people think it’s weird how I call him by his first name, but it’s not like we’re progressive or anything; like everyone else in Friendship, Dom’s a true conservative. He says it’d be stupid to be from Wisconsin, needing oil the way we do in winter, and not vote Republican. When it gets below zero around Christmas, Dom will go out and start my car a half hour before I actually leave for school, just so that it’s warm when I get in it. According to Dom, Republicans are just trying to stay warm.

“Hiya, Nita Fried,” Dom says, sounding way too cheerful in my opinion. “Welcome, welcome.”

Mrs. Fried grimaces. “On the way over here I probably saw a dozen bleeding bucks strapped to the roofs of cars,” she says. “I hate hunting season.” She makes a spitting sound and puts the shoe box down on one of the double beds. Seeing her without anything in her hands makes me want to crawl between her arms, fill up the empty space—not just because I feel bad for her, but because other than the bloodshot eyes and matted hair, she looks exactly the same as she did when Ruth was alive, and that makes me want to hold on to something.

I take a step toward her. “I hate hunting season, too.”

“Please don’t touch me,” she says in a crackly, flat voice, like she can read my mind. She plops down on the bed beside the shoe box. “I’m so tired of hugging people, I could self-immolate.” She looks straight at me. “That means set myself on fire. All day the neighbors have been bringing meat loaves. I hate meat loaf.”

“Okay,” Dom and I say in unison.

“I’m so sorry.” She covers her face with her fingers. “I’m not myself.” She takes a long, shaky breath. “Dominic, could you get me a candy bar or something from the vending machine?” She sighs, drops her hands into her lap, and looks at Dom with tears in her eyes.

“Of course.” Dom pats his pockets for his wallet. “Whatever you need.” He shoots me a reassuring smile and hustles out of the room.

As the door latches behind him, she turns to me. Her face looks like it weighs a hundred pounds. I can feel mine getting hot.

“Hi,” I say.

She gestures to the shoe box. “I brought this for you. Take it.” I walk over and pluck it from the bed. Inside are some pictures that Ruth and I were going to use to make a collage: us at eight years old, wearing boxers on our heads and crawling through her backyard on our elbows like soldiers. The two of us at the third-grade Halloween parade: Ruth as a princess and me as an “animal on TV,” wearing cat ears and a cardboard television on my head with a square cut out for the face.

“I can’t have them,” Mrs. Fried says blankly. She seems mad at me. Does she wish it had been me on my way to her house Friday night, instead of the other way around? Should I apologize for being alive?

Everyone grieves differently, I remind myself. Dom’s only told me that about a bazillion times.

I pick up a photo of Ruth and me with our arms around each other, smiling so big that you can see the matching rubber bands on our braces—green and gold, Green Bay Packers colors. We didn’t even follow football. We were just trying to fit in with the boys at school.

I catch myself accidentally bending the photo. When Mom died, Dom and I hid all the pictures of her for almost a year, not because we couldn’t stand to look at them but because we were afraid to destroy them. The urge was to hold on too tightly—accidentally crumple every photo in our fists because we wanted to absorb the image. I put the pictures back into the shoe box and replace the lid.

“How is the eulogy coming?” Mrs. Fried asks quietly, reaching into her gigantic purse.

“Oh, you know. Fine.” I squat down next to my suitcase and dig through the underwear and socks, tucking the shoe box securely into one of the corners.

She exhales. “There’s something else.” I hear her rustling in her bag and turn to see her tugging out a notebook. “It’s Ruth’s journal. I thought—I don’t know—I thought there might be something sweet in there you could quote at the service.” She bends over and slides it across the carpet. “I can’t handle it right now.”

“Okay.” I pull it toward me. “Thank you.” Quoting from it is a good idea. It’s all I have to go with, at the very least. I turn the notebook over in my hands. “I didn’t know Ruth kept a diary.”

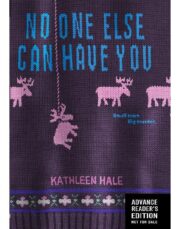

"No One Else Can Have You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No One Else Can Have You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No One Else Can Have You" друзьям в соцсетях.