Subsequently, at the urging of the youngest Bennet girls, Mr Bingley had himself held a ball at Netherfield, and on this occasion Mr Darcy had indeed danced with Elizabeth. The chaperones, ranged in their chairs against the wall, had raised their lorgnettes and, like the rest of the company, studied the pair carefully as they made their way down the line. Certainly there had been little conversation between them but the very fact that Mr Darcy had actually asked Miss Elizabeth to dance and had not been refused was a matter for interest and speculation.

The next stage in Elizabeth’s campaign was her visit, with Sir William Lucas and his daughter Maria, to Mr and Mrs Collins at Hunsford Parsonage. Normally this was surely an invitation which Miss Lizzy should have refused. What possible pleasure could any rational woman take in six weeks of Mr Collins’s company? It was generally known that, before his acceptance by Miss Lucas, Miss Lizzy had been his first choice of bride. Delicacy, apart from any other consideration, should have kept her away from Hunsford. But she had, of course, been aware that Lady Catherine de Bourgh was Mr Collins’s neighbour and patroness, and that her nephew, Mr Darcy, would almost certainly be at Rosings while the visitors were at the parsonage. Charlotte, who kept her mother informed of every detail of her married life, including the health of her cows, poultry and husband, had written subsequently to say that Mr Darcy and his cousin, Colonel Fitzwilliam, who was also visiting Rosings, had called at the parsonage frequently during Elizabeth’s stay and that Mr Darcy on one occasion had visited without his cousin when Elizabeth had been on her own. Mrs Collins was certain that this distinction must confirm that he was falling in love and wrote that, in her opinion, her friend would have taken either gentleman with alacrity had an offer been made; Miss Lizzy had however returned home with nothing settled.

But at last all had come right when Mrs Gardiner and her husband, who was Mrs Bennet’s brother, had invited Elizabeth to accompany them on a summer tour of pleasure. It was to have been as far as the Lakes, but Mr Gardiner’s business responsibilities had apparently dictated a more limited scheme and they would go no further north than Derbyshire. It was Kitty, the fourth Bennet daughter, who had conveyed this news, but no one in Meryton believed the excuse. A wealthy family who could afford to travel from London to Derbyshire could clearly extend the tour to the Lakes had they wished. It was obvious that Mrs Gardiner, a partner in her favourite niece’s matrimonial scheme, had chosen Derbyshire because Mr Darcy would be at Pemberley, and indeed the Gardiners and Elizabeth, who had no doubt enquired at the inn when the master of Pemberley would be at home, were actually visiting the house when Mr Darcy returned. Naturally, as a matter of courtesy, the Gardiners were introduced and the party invited to dine at Pemberley, and if Miss Elizabeth had entertained any doubts about the wisdom of her scheme to secure Mr Darcy, the first sight of Pemberley had confirmed her determination to fall in love with him at the first convenient moment. Subsequently he and his friend Mr Bingley had returned to Netherfield Park and had lost no time in calling at Longbourn where the happiness of Miss Bennet and Miss Elizabeth was finally and triumphantly secured. The engagement, despite its brilliance, gave less pleasure than had Jane’s. Elizabeth had never been popular, indeed the more perceptive of the Meryton ladies occasionally suspected that Miss Lizzy was privately laughing at them. They also accused her of being sardonic, and although there was uncertainty about the meaning of the word, they knew that it was not a desirable quality in a woman, being one which gentlemen particularly disliked. Neighbours whose jealousy of such a triumph exceeded any satisfaction in the prospect of the union were able to console themselves by averring that Mr Darcy’s pride and arrogance and his wife’s caustic wit would ensure that they lived together in the utmost misery for which even Pemberley and ten thousand a year could offer no consolation.

Allowing for such formalities without which grand nuptials could hardly be valid, the taking of likenesses, the busyness of lawyers, the buying of new carriages and wedding clothes, the marriage of Miss Bennet to Mr Bingley and Miss Elizabeth to Mr Darcy took place on the same day at Longbourn church with surprisingly little delay. It would have been the happiest day of Mrs Bennet’s life had she not been seized with palpitations during the service, brought on by fear that Mr Darcy’s formidable aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, might appear in the church door to forbid the marriage, and it was not until after the final blessing that she could feel secure in her triumph.

It is doubtful whether Mrs Bennet missed the company of her second daughter, but her husband certainly did. Elizabeth had always been his favourite child. She had inherited his intelligence, something of his sharp wit, and his pleasure in the foibles and inconsistencies of their neighbours, and Longbourn House was a lonelier and less rational place without her company. Mr Bennet was a clever and reading man whose library was both a refuge and the source of his happiest hours. He and Darcy rapidly came to the conclusion that they liked each other and thereafter, as is common with friends, accepted their different quirks of character as evidence of the other’s superior intellect. Mr Bennet’s visits to Pemberley, frequently made when he was least expected, were chiefly spent in the library, one of the finest in private hands, from which it was difficult to extract him, even for meals. He visited the Bingleys at Highmarten less frequently since, apart from Jane’s excessive preoccupation with the comfort and well-being of her husband and children, which occasionally Mr Bennet found irksome, there were few new books and periodicals to tempt him. Mr Bingley’s money had originally come from trade. He had inherited no family library and had only thought of setting one up after his purchase of Highmarten House. In this project both Darcy and Mr Bennet were very ready to assist. There are few activities so agreeable as spending a friend’s money to your own satisfaction and his benefit, and if the buyers were periodically tempted to extravagance, they comforted themselves with the thought that Bingley could afford it. Although the library shelves, designed to Darcy’s specification and approved by Mr Bennet, were as yet by no means full, Bingley was able to take pride in the elegant arrangement of the volumes and the gleaming leather of the bindings, and occasionally even opened a book and was seen reading it when the season or the weather was unpropitious for hunting, fishing or shooting.

Mrs Bennet had only accompanied her husband to Pemberley on two occasions. She had been received by Mr Darcy with kindness and forbearance but was too much in awe of her son by marriage to wish to repeat the experience. Indeed, Elizabeth suspected that her mother had greater pleasure in regaling her neighbours with the wonders of Pemberley, the size and beauty of the gardens, the grandeur of the house, the number of servants and the splendour of the dining table than she had in experiencing them. Neither Mr Bennet nor his wife were frequent visitors of their grandchildren. Five daughters born in quick succession had left them with a lively memory of broken nights, screaming babies, a head nurse who complained constantly, and recalcitrant nursery maids. A preliminary inspection shortly after the birth of each grandchild confirmed the parents’ assertion that the child was remarkably handsome and already exhibiting a formidable intelligence, after which they were content to receive regular progress reports.

Mrs Bennet, greatly to her two elder daughters’ discomfort, had loudly proclaimed at the Netherfield ball that she expected Jane’s marriage to Mr Bingley to throw her younger daughters in the way of other wealthy men, and to general surprise it was Mary who dutifully fulfilled this very natural maternal prophecy. No one expected Mary to marry. She was a compulsive reader but without discrimination or understanding, an assiduous practiser at the pianoforte but devoid of talent, and a frequent deliverer of platitudes which had neither wisdom nor wit. Certainly she never displayed any interest in the male sex. An assembly ball was a penance to be endured only because it offered an opportunity for her to take centre stage at the pianoforte and, by the judicious use of the sustaining pedal, to stun the audience into submission. But within two years of Jane’s marriage, Mary was the wife of the Reverend Theodore Hopkins, the rector of the parish adjacent to Highmarten.

The Highmarten vicar had been indisposed and Mr Hopkins had for three Sundays taken the services. He was a thin, melancholy bachelor, aged thirty-five, given to preaching sermons of inordinate length and complicated theology, and had therefore naturally acquired the reputation of being a very clever man, and although he could hardly be described as rich, he enjoyed a more than adequate private income in addition to his stipend. Mary, a guest at Highmarten on one of the Sundays on which he preached, was introduced to him by Jane at the church door after the service and immediately impressed him by her compliments on his discourse, her endorsement of the interpretation he had taken of the text, and such frequent references to the relevance of Fordyce’s sermons that Jane, anxious for her husband and herself to get away to their Sunday luncheon of cold meats and salad, invited him to dinner on the following day. Further invitations followed and within three months Mary became Mrs Theodore Hopkins with as little public interest in the marriage as there had been display at the ceremony.

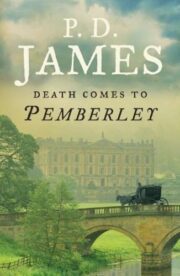

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.