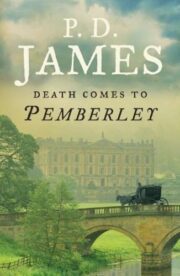

P. D. James

Death Comes to Pemberley

To Joyce McLennan

Friend and personal assistant who has typed my

novels for thirty-five years

With affection and gratitude

Author’s Note

I owe an apology to the shade of Jane Austen for involving her beloved Elizabeth in the trauma of a murder investigation, especially as in the final chapter of Mansfield Park Miss Austen made her views plain: “Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery. I quit such odious subjects as soon as I can, impatient to restore everybody not greatly in fault themselves to tolerable comfort, and to have done with all the rest.” No doubt she would have replied to my apology by saying that, had she wished to dwell on such odious subjects, she would have written this story herself, and done it better.

P. D. James, 2011

Prologue

The Bennets of Longbourn

It was generally agreed by the female residents of Meryton that Mr and Mrs Bennet of Longbourn had been fortunate in the disposal in marriage of four of their five daughters. Meryton, a small market town in Hertfordshire, is not on the route of any tours of pleasure, having neither beauty of setting nor a distinguished history, while its only great house, Netherfield Park, although impressive, is not mentioned in books about the county’s notable architecture. The town has an assembly room where dances are regularly held but no theatre, and the chief entertainment takes place in private houses where the boredom of dinner parties and whist tables, always with the same company, is relieved by gossip.

A family of five unmarried daughters is sure of attracting the sympathetic concern of all their neighbours, particularly where other diversions are few, and the situation of the Bennets was especially unfortunate. In the absence of a male heir, Mr Bennet’s estate was entailed on his nephew, the Reverend William Collins, who, as Mrs Bennet was fond of loudly lamenting, could turn her and her daughters out of the house before her husband was cold in his grave. Admittedly, Mr Collins had attempted to make such redress as lay in his power. At some inconvenience to himself, but with the approval of his formidable patroness Lady Catherine de Bourgh, he had left his parish at Hunsford in Kent to visit the Bennets with the charitable intention of selecting a bride from the five daughters. This intention was received by Mrs Bennet with enthusiastic approval but she warned him that Miss Bennet, the eldest, was likely to be shortly engaged. His choice of Elizabeth, the second in seniority and beauty, had met with a resolute rejection and he had been obliged to seek a more sympathetic response to his pleading from Elizabeth’s friend Miss Charlotte Lucas. Miss Lucas had accepted his proposal with gratifying alacrity and the future which Mrs Bennet and her daughters could expect was settled, not altogether to the general regret of their neighbours. On Mr Bennet’s death, Mr Collins would install them in one of the larger cottages on the estate where they would receive spiritual comfort from his administrations and bodily sustenance from the leftovers from Mrs Collins’s kitchen augmented by the occasional gift of game or a side of bacon.

But from these benefits the Bennet family had a fortunate escape. By the end of 1799 Mrs Bennet could congratulate herself on being the mother of four married daughters. Admittedly the marriage of Lydia, the youngest, aged only sixteen, was not propitious. She had eloped with Lieutenant George Wickham, an officer in the militia which had been stationed at Meryton, an escapade which was confidently expected to end, as all such adventures deserve, in her desertion by Wickham, banishment from her home, rejection from society and the final degradation which decency forbade the ladies to mention. The marriage had, however, taken place, the first news being brought by a neighbour, William Goulding, when he rode past the Longbourn coach and the newly married Mrs Wickham placed her hand on the open window so that he could see the ring. Mrs Bennet’s sister, Mrs Philips, was assiduous in circulating her version of the elopement, that the couple had been on their way to Gretna Green but had made a short stop in London to enable Wickham to inform a godmother of his forthcoming nuptials, and, on the arrival of Mr Bennet in search of his daughter, the couple had accepted the family’s suggestion that the intended marriage could more conveniently take place in London. No one believed this fabrication, but it was acknowledged that Mrs Philips’s ingenuity in devising it deserved at least a show of credulity. George Wickham, of course, could never be accepted in Meryton again to rob the female servants of their virtue and the shopkeepers of their profit, but it was agreed that, should his wife come among them, Mrs Wickham should be afforded the tolerant forbearance previously accorded to Miss Lydia Bennet.

There was much speculation about how the belated marriage had been achieved. Mr Bennet’s estate was hardly worth two thousand pounds a year, and it was commonly felt that Mr Wickham would have held out for at least five hundred and all his Meryton and other bills being paid before consenting to the marriage. Mrs Bennet’s brother, Mr Gardiner, must have come up with the money. He was known to be a warm man, but he had a family and no doubt would expect repayment from Mr Bennet. There was considerable anxiety in Lucas Lodge that their son-in-law’s inheritance might be much diminished by this necessity, but when no trees were felled, no land sold, no servants put off and the butcher showed no disinclination to provide Mrs Bennet with her customary weekly order, it was assumed that Mr Collins and dear Charlotte had nothing to fear and that, as soon as Mr Bennet was decently buried, Mr Collins could take possession of the Longbourn estate with every confidence that it had remained intact.

But the engagement which followed shortly after Lydia’s marriage, that of Miss Bennet and Mr Bingley of Netherfield Park, was received with approbation. It was hardly unexpected; Mr Bingley’s admiration for Jane had been apparent from their first meeting at an assembly ball. Miss Bennet’s beauty, gentleness and the naive optimism about human nature which inclined her never to speak ill of anyone made her a general favourite. But within days of the engagement of her eldest to Mr Bingley being announced, an even greater triumph for Mrs Bennet was noised abroad and was at first received with incredulity. Miss Elizabeth Bennet, the second daughter, was to marry Mr Darcy, the owner of Pemberley, one of the greatest houses in Derbyshire and, it was rumoured, with an income of ten thousand pounds a year.

It was common knowledge in Meryton that Miss Lizzy hated Mr Darcy, an emotion in general held by those ladies and gentlemen who had attended the first assembly ball at which Mr Darcy had been present with Mr Bingley and his two sisters, and at which he had given adequate evidence of his pride and arrogant disdain of the company, making it clear, despite the prompting of his friend Mr Bingley, that no woman present was worthy to be his partner. Indeed, when Sir William Lucas had introduced Elizabeth to him, Mr Darcy had declined to dance with her, later telling Mr Bingley that she was not pretty enough to tempt him. It was taken for granted that no woman could be happy as Mrs Darcy for, as Maria Lucas pointed out, “Who would want to have that disagreeable face opposite you at the breakfast table for the rest of your life?”

But there was no cause to blame Miss Elizabeth Bennet for taking a more prudent and optimistic view. One cannot have everything in life and any young lady in Meryton would have endured more than a disagreeable face at the breakfast table to marry ten thousand a year and to be mistress of Pemberley. The ladies of Meryton, as in duty bound, were happy to sympathise with the afflicted and to congratulate the fortunate but there should be moderation in all things, and Miss Elizabeth’s triumph was on much too grand a scale. Although they conceded that she was pretty enough and had fine eyes, she had nothing else to recommend her to a man with ten thousand a year and it was not long before a coterie of the most influential gossips concocted an explanation: Miss Lizzy had been determined to capture Mr Darcy from the moment of their first meeting. And when the extent of her strategy had become apparent it was agreed that she had played her cards skilfully from the very beginning. Although Mr Darcy had declined to dance with her at the assembly ball, his eyes had been frequently on her and her friend Charlotte who, after years of husband-seeking, was extremely adroit at identifying any sign of a possible attachment, and had warned Elizabeth against allowing her obvious partiality for the attractive and popular Lieutenant George Wickham to cause her to offend a man of ten times his consequence.

And then there was the incident of Miss Bennet’s dinner engagement at Netherfield when, due to her mother’s insistence on her riding rather than taking the family coach, Jane had caught a very convenient cold and, as Mrs Bennet had planned, was forced to stay for several nights at Netherfield. Elizabeth, of course, had set out on foot to visit her, and Miss Bingley’s good manners had impelled her to offer hospitality to the unwelcome visitor until Miss Bennet recovered. Nearly a week spent in the company of Mr Darcy must have enhanced Elizabeth’s hopes of success and she would have made the best of this enforced intimacy.

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.