The first ball at which Elizabeth had stood as hostess with her husband at the top of the staircase to greet the ascending guests had in prospect been somewhat of an ordeal, but she had survived the occasion triumphantly. She was fond of dancing and could now say that the ball gave her as much pleasure as it did her guests. Lady Anne had meticulously set out in her elegant handwriting her plans for the occasion, and her notebook, with its fine leather cover stamped with the Darcy crest, was still in use and that morning had been laid open before Elizabeth and Mrs Reynolds. The guest list was still fundamentally the same but the names of Darcy’s and Elizabeth’s friends had been added, including her aunt and uncle, the Gardiners, while Bingley and Jane came as a matter of course and this year, as last, would be bringing their house guest, Henry Alveston, a young lawyer who, handsome, clever and lively, was as welcome at Pemberley as he was at Highmarten.

Elizabeth had no worries about the success of the ball. All the preparations, she knew, had been made. Logs in sufficient quantity had been cut to ensure that the fires would be kept up, particularly in the ballroom. The pastry cook would wait until the morning to prepare the delicate tarts and savouries which were so enjoyed by the ladies, while birds and animals had been slaughtered and hung to provide the more substantial meal which the men would expect. Wine had already been brought up from the cellars and almonds had been grated to provide the popular white soup in sufficient quantities. The negus, which would greatly improve its flavour and potency and contribute considerably to the gaiety of the occasion, would be added at the last moment. The flowers and plants had been chosen from the hothouses ready to be placed in buckets in the conservatory for Elizabeth and Georgiana, Darcy’s sister, to supervise their arrangement tomorrow afternoon; and Thomas Bidwell, from his cottage in the woodland, would even now be seated in the pantry polishing the dozens of candlesticks which would be required for the ballroom, the conservatory and the small sitting room reserved for the female guests. Bidwell had been head coachman to the late Mr Darcy, as his father had been to the Darcys before him. Now rheumatism in both his knees and his back made it impossible for him to work with the horses, but his hands were still strong and he spent every evening of the week before the ball polishing the silver, helping to dust the extra chairs required for the chaperones and making himself indispensible. Tomorrow the carriages of the landowners and the hired chaises of the humbler guests would bowl up the drive to disgorge the chattering passengers, their muslin gowns and glittering headdresses cloaked against the autumn chill, eager again for the remembered pleasures of Lady Anne’s ball.

In all the preparations Mrs Reynolds had been Elizabeth’s reliable helpmeet. Elizabeth and she had first met when, with her aunt and uncle, she had visited Pemberley and had been received and shown round by the housekeeper, who had known Mr Darcy since he was a boy and had been so profuse in his praise, both as a master and as a man, that Elizabeth had for the first time wondered whether her prejudice against him had done him an injustice. She had never spoken of the past to Mrs Reynolds, but she and the housekeeper had become friends and Mrs Reynolds, with tactful support, had been invaluable to Elizabeth, who had recognised even before her first arrival at Pemberley as a bride that being mistress of such a house, responsible for the well-being of so many employees, would be very different from her mother’s task of running Longbourn. But her kindness and interest in the lives of her servants made them confident that this new mistress had their welfare at heart and all was easier than she had expected, in fact less onerous than managing Longbourn since the servants at Pemberley, the majority of long service, had been trained by Mrs Reynolds and Stoughton, the butler, in the tradition that the family were never to be inconvenienced and were entitled to expect immaculate service.

Elizabeth missed little of her previous life, but it was to the servants at Longbourn that her thoughts most frequently turned: Hill the housekeeper, who had been privy to all their secrets, including Lydia’s notorious elopement, Wright the cook, who was uncomplaining about Mrs Bennet’s somewhat unreasonable demands, and the two maids who combined their duties with acting as ladies’ maids to Jane and herself, arranging their hair before the assembly balls. They had become part of the family in a way the servants at Pemberley could never be, but she knew that it was Pemberley, the house and the Darcys, which bound family, staff and tenants together in a common loyalty. Many of them were the children and grandchildren of previous servants, and the house and its history were in their blood. And she knew, too, that it was the birth of the two fine and healthy boys upstairs in the nursery – Fitzwilliam, who was nearly five and Charles, who was just two – which had been her final triumph, an assurance that the family and its heritage would endure to provide work for them and for their children and grandchildren and that there would continue to be Darcys at Pemberley.

Nearly six years earlier Mrs Reynolds, conferring over the guest list, menu and flowers for Elizabeth’s first dinner party, had said, “It was a happy day for us all, madam, when Mr Darcy brought home his bride. It was the dearest wish of my mistress that she would live to see her son married. Alas, it was not to be. I knew how anxious she was, both for his own sake and for Pemberley, that he should be happily settled.”

Elizabeth’s curiosity had overcome discretion. She had occupied herself by moving papers on her desk without looking up, saying lightly, “But not perhaps with this wife. Was it not settled by Lady Anne Darcy and her sister that a match should be made between Mr Darcy and Miss de Bourgh?”

“I am not saying, madam, that Lady Catherine might not have had such a plan in mind. She brought Miss de Bourgh to Pemberley often enough when Mr Darcy was known to be here. But it would never have been. Miss de Bourgh, poor lady, was always sickly and Lady Anne placed great store on good health in a bride. We did hear that Lady Catherine was hoping Miss de Bourgh’s other cousin, Colonel Fitzwilliam, would make an offer, but nothing came of it.”

Recalling her mind to the present, Elizabeth slipped Lady Anne’s notebook into a drawer and then, reluctant to leave the peace and solitude which she could not now hope to enjoy until the ball was safely over, walked over to one of the two windows which gave a view of the long curving drive to the house and the river, fringed by the famous Pemberley wood. This had been planted under the direction of a notable landscape gardener some generations earlier. Each tree at the edge, perfect in form and hung with the warm golden flags of autumn, stood a little apart from the others as if to emphasise its singular beauty, and the planting then became denser as the eyes were cunningly drawn towards the rich loam-smelling solitude of the interior. There was a second and larger wood to the north-west in which the trees and bushes had been allowed to grow naturally and which had been a playground and secret refuge from the nursery for Darcy as a boy. His great-grandfather who, on inheriting the estate, became a recluse, had built a cottage there in which he had shot himself, and the wood – referred to as the woodland to distinguish it from the arboretum – had induced a superstitious fear in the servants and tenants of Pemberley and was seldom visited. A narrow lane ran through it to a second entrance to Pemberley, but this was used mainly by tradesmen and the guests to the ball would sweep up the main drive, their vehicles and horses accommodated in the stables and their coachmen entertained in the kitchens while the ball was in progress.

Lingering at the window and putting aside the concerns of the day, Elizabeth let her eyes rest on the familiar and calming but ever-changing beauty. The sun was shining from a sky of translucent blue in which only a few frail clouds dissolved like wisps of smoke. Elizabeth knew from the short walk which she and her husband usually took at the beginning of the day that the winter sunshine was deceptive, and a chilling breeze, for which she was ill prepared, had driven them quickly home. Now she saw that the wind had strengthened. The surface of the river was creased with small waves which spent themselves among the grasses and shrubs bordering the stream, their broken shadows trembling on the agitated water.

She saw that two people were braving the morning chill; Georgiana and Colonel Fitzwilliam had been walking beside the river and now were turning towards the greensward and the stone steps leading to the house. Colonel Fitzwilliam was in uniform, his red tunic a vivid splash of colour against the soft blue of Georgiana’s pelisse. They were walking a little distanced but, she thought, companionably, occasionally pausing as Georgiana clutched at her hat which was in danger of being swept away by the wind. As they approached, Elizabeth drew back from the window, anxious that they should not feel that they were being spied upon, and returned to her desk. There were letters to be written, invitations to be replied to, and decisions to be made on whether any of the cottagers were in poverty or grief and would welcome a visit conveying her sympathy or practical help.

She had hardly taken up her pen when there was a gentle knock on the door and the reappearance of Mrs Reynolds. “I’m sorry to disturb you madam, but Colonel Fitzwilliam has just come in from a walk and has asked whether you can spare him some minutes, if it is not too inconvenient.”

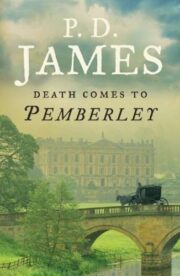

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.