Elizabeth said, “I’m free now, if he would like to come up.”

Elizabeth thought she knew what he might have to communicate and it would be an anxiety which she would have been glad to be spared. Darcy had few close relations and from boyhood his cousin, Colonel Fitzwilliam, had been a frequent visitor to Pemberley. During his early military career he had appeared less often but during the last eighteen months his visits had become shorter but more frequent and Elizabeth had noticed that there had been a difference, subtle but unmistakable, in his behaviour to Georgiana – he smiled more often when she was present and showed a greater readiness than previously to sit by her when he could and engage her in conversation. Since his visit last year for Lady Anne’s ball there had been a material change in his life. His elder brother, who had been heir to the earldom, had died abroad and he had now inherited the title of Viscount Hartlep and was the acknowledged heir. He preferred not to use his present title, particularly when among friends, deciding to wait until he succeeded before assuming his new name and the many responsibilities it would bring, and he was still generally known as Colonel Fitzwilliam.

He would, of course, be looking to marry, especially now when England was at war with France and he might be killed in action without leaving an heir. Although Elizabeth had never concerned herself with the family tree, she knew that there was no close male relative and that if the colonel died without leaving a male child the earldom would lapse. She wondered, and not for the first time, whether he was seeking a wife at Pemberley and, if so, how Darcy would react. It must surely be agreeable to him that his sister should one day become a countess and her husband a member of the House of Lords and a legislator of his country. All that was a reason for justifiable family pride, but would Georgiana share it? She was now a mature woman and no longer subject to guardianship, but Elizabeth knew that it would grieve Georgiana greatly if she contemplated marriage with a man of whom her brother could not approve; and there was the complication of Henry Alveston. Elizabeth had seen enough to make her sure that he was in love, or on the verge of love, but what of Georgiana? Of one thing Elizabeth was certain, Georgiana Darcy would never marry without love, or without that strong attraction, affection and respect which a woman could assure herself would deepen into love. Would not that have been enough for Elizabeth herself if Colonel Fitzwilliam had proposed while he was visiting his aunt, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, at Rosings? The thought that she might unwittingly have lost Darcy and her present happiness to grasp at an offer from his cousin was even more humiliating than the memory of her partiality for the infamous George Wickham and she thrust it resolutely aside.

The colonel had arrived at Pemberley the previous evening in time for dinner, but apart from greeting him they had been little together. Now, as he quietly knocked and entered and at her invitation took the proffered chair opposite her beside the fire, it seemed to her that she saw him clearly for the first time. He was five years Darcy’s senior, but when they had first met in the drawing room at Rosings his cheerful good humour and attractive liveliness had emphasised his cousin’s taciturnity and he had seemed the younger. But all that was over. He now had a maturity and a seriousness which made him seem older than she knew him to be. Some of this must, she thought, have been due to his army service and the great responsibilities he bore as a commander of men, while the change in his status had brought with it not only a greater gravity but, she thought, a more visible family pride and indeed a trace of arrogance, which were less attractive.

He did not immediately speak and there was a silence during which she made up her mind that, as he had asked for a meeting, it was for him to speak first. He seemed to be concerned how best to proceed but did not appear either embarrassed or ill at ease. Finally, leaning towards her, he spoke. “I am confident, my dear cousin, that with your keen eye and your interest in the lives and concerns of other people you will not be entirely ignorant of what I am about to say. As you know, I have been privileged since the death of my aunt Lady Anne Darcy to be joined with Darcy as guardian of his sister and I think I can say that I have carried out my duties with a deep sense of my responsibilities and a fraternal affection for my ward which has never wavered. It has now deepened into the love which a man should feel for the woman he hopes to marry and it is my dearest wish that Georgiana should consent to be my wife. I have made no formal application to Darcy but he is not without perception and I am not without hope that my proposal will have his approval and consent.”

Elizabeth thought it wiser not to point out that, since Georgiana had reached her majority, no consent was now necessary. She said, “And Georgiana?”

“Until I have Darcy’s approval I cannot feel justified in speaking. At present I acknowledge that Georgiana has said nothing to give me grounds for active hope. Her attitude to me as always is one of friendship, trust and, I believe, affection. I hope that trust and affection may grow into love if I am patient. It is my belief that, for a woman, love more often comes after marriage than before it and, indeed, it seems to me both natural and right that it should. I have, after all, known her since her birth. I acknowledge that the age difference might present a problem, but I am only five years older than Darcy and I cannot see it as an impediment.”

Elizabeth felt she was on dangerous ground. She said, “Age may be no impediment, but an existing partiality may well be.”

“You are thinking of Henry Alveston? I know that Georgiana likes him but I see nothing to suggest a deeper attachment. He is an agreeable, clever and excellent young man. I hear nothing but good of him. And he may well have hopes. Naturally he must look to marry money.”

Elizabeth turned away. He added quickly, “I intend no imputation of avarice or insincerity, but with his responsibilities, his admirable resolve to revive the family fortune and his energetic efforts to restore the estate and one of the most beautiful houses in England, he cannot afford to marry a poor woman. It would condemn them both to unhappiness, even penury.”

Elizabeth was silent. She was thinking again of that first meeting at Rosings, of their talking together after dinner, the music and the laughter and his frequent visits to the parsonage, his attentions to her which had been too obvious to escape notice. On the evening of the dinner party Lady Catherine had certainly seen enough to worry her. Nothing escaped her sharp inquisitive eye. Elizabeth remembered how she had called out, “What is it you are talking of? I must have a share in the conversation.” Elizabeth knew that she had begun to wonder whether this man was one with whom she could be happy, but the hope, if it had been strong enough to be called a hope, had died when a little later they had met, perhaps by accident, perhaps by design on his part, when she had been walking alone in the grounds of Rosings and he had turned to accompany her back to the vicarage. He had been deploring his poverty and she had teased him by asking what disadvantages this poverty brought to the younger son of an earl. He had replied that the younger sons “cannot marry where they like”. At the time she had wondered whether the remark had held a warning and the suspicion had caused her some embarrassment which she had attempted to hide by turning the conversation into a pleasantry. But the memory of the incident had been far from pleasant. She had not needed Colonel Fitzwilliam’s warning to remind her of what a girl with four unmarried sisters and no fortune could expect in marriage. Was he saying that it was safe for a fortunate young man to enjoy the company of such a woman, even to flirt with discretion, but prudence dictated that she must not be led to hope for more? The warning might have been necessary but it had not been well done. If he had never entertained the thought of her it would have been kinder had he been less openly assiduous in his attentions.

Colonel Fitzwilliam was aware of her silence. He said, “I may hope for your approval?”

She turned to him and said firmly, “Colonel, I can have no part in this. It must be for Georgiana to decide where her happiness may best lie. I can only say that if she does agree to marry you I would fully share my husband’s pleasure in such a union. But this is not a matter I could influence. It must be for Georgiana.”

“I thought she may have spoken to you?”

“She has not confided in me and it would not be proper for me to raise this matter with her until, or if, she chooses to do so.”

This seemed for a moment to satisfy him, but then, as if under a compulsion, he returned to the man he suspected could be his rival. “Alveston is a handsome and agreeable young man and he speaks well. Time and greater maturity will no doubt moderate a certain overconfidence and a tendency to show less respect for his elders than is proper at his age and which is regrettable in one so able. I doubt not that he is a welcome guest at Highmarten but I find it surprising that he is able to visit Mr and Mrs Bingley so frequently. Successful lawyers are usually not so prodigal with their time.”

Elizabeth made no reply and he perhaps thought that the criticism, both actual and implied, had been injudicious. He added, “But then he is usually in Derbyshire on Saturday or Sunday or when the courts are not sitting. I assume he studies whenever he is at leisure.”

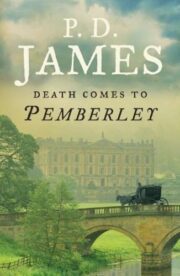

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.