The water began to boil behind me and I poured in the pasta and gave it a quick stir, then slid into the chair across from my grandfather as he counted out twenty-six cards for each of us.

“Quite a storm we had this afternoon, wasn’t it?” he said absently as he dealt.

I bit my lip. I didn’t want to talk about it. I wasn’t ready yet to confess to him that I felt guilty for how I’d lost it down there. For how I’d attacked my grandmother.

“You know, we get pretty intense storms around here all summer long. Break off our tomato plants, blow the barbecue grill to the other side of the porch. One time we had hail so big it busted out the skylights.”

I picked up my cards. What was he getting at?

He gathered his cards and leveled his gaze at me. He didn’t look angry, but he did look serious. “We’ve never once had a tornado here. In all my sixty-two years, not one.”

I understood what he was getting at—that I needed to let go of my fears because the chances of ever being in another tornado were so slim. The devastation in Elizabeth was unexpected for a reason—because tornadoes as huge as ours almost never happen. It was a freak accident, losing my family. That fact didn’t make it suck any less, but the chances that it would happen again were almost zero. And I couldn’t keep living my life expecting tragedy around every corner.

“You said you learned how to play in the service,” I said, trying to change the subject. “Were you ever in a war?”

“It’s a long story,” he said. “But yes.”

And maybe it was because playing cards relaxed me. Or maybe it was because I felt guilty for what I’d done to my grandmother. Or maybe I had finally gotten so lonely, so sick of my thoughts being my only company. I suddenly wanted to talk.

“I’ve got time,” I said.

So he proceeded to tell me about the Vietnam War, where he was a young private, barely out of high school, scared for his life. He told me how he’d felt insanely homesick and how every cross word he’d ever uttered to anyone he loved plagued him as he watched young men dying around him every day. He said he’d lie awake at night and replay all the good times and bad that he’d had with his family, hoping that if he died, they’d only remember the good. He’d never had a girlfriend before he got enlisted, and he worried that he’d die over there and never know what it was like to fall in love.

“That was the worst,” he said. “I would rather have had someone to love and left her too soon than die never knowing love at all.” He let that sink in while we flipped cards over. “But,” he said with renewed vigor, “turned out I wasn’t supposed to find Patty before I went. I met her the day after I got home, can you believe that? The day after.”

I rooted through my cards, then drew a nine that I needed and laid it down. “Why didn’t you talk to my mom again? I mean… after she split up with Clay.”

My grandfather drew a card and studied it. “I wish we had” was all he said.

There was a sizzling sound as the pot of water boiled over. I jumped up to stir it and turn the flame down, absently setting my cards on the edge of the table. They fell off with a whisper, spreading themselves across the linoleum floor. I calmed the overflowing pot, then went down to my knees to pick up the cards, which had fanned underneath a side table.

That’s when I noticed it for the first time—a porcelain kitten tucked away on a low shelf. I picked it up and turned it over in my hands, forgetting about the cards as I stood up.

It was a glossy orange-and-white tabby with a number three on its chest, pawing at a purple butterfly.

I held it out to my grandfather, feeling like someone had stolen my breath. “Where did you get this?” I asked.

He frowned at it over his glasses in the same maddeningly nonchalant way he did everything. “That? Oh, I think it belonged to Christine. Her mother bought her one for her birthday every year. Christine loved cats. She treasured that collection. She left the whole thing behind.” He took the kitten out of my hand and looked it over. “Your grandma packed them all up and put them away. All except this one. She keeps it out because it was Chrissy’s favorite.” He set the statue on the table between us. My eyes felt riveted to it as pieces of my life snapped into place. “You’d better tend to that pot,” he said. “It’s fixing to boil over again.”

I walked over and took the pot off the stove, then searched until I found a colander and drained the pasta, stirred in the cheese and butter and milk. But I did these things on autopilot. In my mind, all I could see was a padded manila envelope, one each year, sitting on our old kitchen table back in Elizabeth.

“It’s another kitten, I’ll bet!” I could hear myself say excitedly, a birthday girl waiting for cake and presents.

I could see the sour look on my mother’s face as she watched me tear open the envelope year after year. I’d always assumed she’d looked so sour because they had come from Clay. I’d always assumed that was why Marin never got one.

But how could Mom tell me? How could she tell me they were from the grandparents she’d raised me to believe were so mean? How could she admit that they weren’t absent after all, but were reaching out to me in the only way they knew how?

On second thought… how couldn’t she tell me these things? How could she be so stubborn? How could she be the cruel one?

Because she’d never in a million years thought I’d find out, that was how. She’d never have guessed that one day I would be playing Spit with her father at the kitchen table she’d grown up eating on. Whatever grudge match had occurred between them, she’d never thought I’d learn about it.

I took a bowl out of the cabinet and spooned in some macaroni.

“You got any extra? I’m not really in the mood for peanut butter and jelly,” my grandfather said.

I glanced over to find that he had picked up my spilled cards and dealt.

“Cheater. I didn’t see you deal those,” I said, reaching up to pull down a second bowl.

He spread his palms over his chest, making a show of innocence. “Cheater? I’m an innocent old man,” he said.

“Uh-huh,” I said, carrying the bowls to the table and setting one in front of him. “Redeal, old man.”

He swept the cards together and shuffled, chuckling, as I blew into my bowl to cool it off, keeping one eye on the kitten the whole time. I’d treated these people horribly. I’d refused to speak to them, refused to be pleasant. I’d said awful things to my grandmother, and her only response had been to tell me she loved me. My grandfather had invited me to play with him. They understood, even when I was being unfair and selfish and ugly.

They’d acted like… family. Like they were offering a place to belong. I just had to take it.

My grandfather started laying cards out on the table again. “As if I need to cheat,” he blustered, “against a girl with purple hair.”

CHAPTER

TWENTY-EIGHT

As dire as the sky had looked the day before, it looked that much brighter the next morning, as if the sun were trying to make up for lost opportunity. For the first time since arriving at my grandparents’ house, I awoke without one of them waking me, a shaft of sunlight warm across my face, like a caress.

The night before, after Grandpa Barry and I had played Spit and then three hands of rummy, I’d made brownies from a box I found in the back of the pantry. I’d placed the plate of brownies on the table between us and poured two glasses of milk. I taught him how to play Seven Bridge, and he won the first game, which included a lot of crowing and laughter on his part. I blamed the loss on distraction. How was I supposed to concentrate on the cards with the kitten in the center of the table?

Grandpa Barry was good at keeping me from brooding. We chatted about places that had the best ice cream, whether or not soccer was a boring sport, books we’d read, and the Waverly theater company, which he thought had a summer program that I could get involved with if I wanted.

Not one word about storms or tornadoes or my freakout or the way I’d been acting or the lifelong grudge my mother had held against them. Just brownies and milk and cards.

And for a few minutes, none of that reminded me of Mom or Marin.

When I realized that I had spent time not thinking about them, I instantly felt guilty. I tried to call up their faces in my mind. They were fuzzy, but they were still there. I imagined their voices as they spoke to me. I was pretty sure I could remember those. I told myself that eating brownies and playing cards wasn’t going to make them deader. It wasn’t like a bowl of macaroni and cheese with my grandfather meant I was forgetting they ever existed.

I pulled myself out of bed, showered and dressed, then padded into the kitchen, where my grandmother sat over a newspaper, a pen in her hand. She looked surprised to see me but didn’t say a word as I passed by. I tried to act as if everything was totally normal between us, going to the fridge to grab a cup of yogurt I’d seen in there the night before.

I sat across from her and ripped off the top of my yogurt. “Where’s Grandpa Barry?”

“He went into town to pick up a few yard supplies. Got some fertilizing to do this weekend,” she said. She leaned over and wrote something into a crossword.

“He going to be gone long?” I spooned yogurt into my mouth, my heart beating, knowing what I was about to ask.

“Oh, a little while,” she said. “You never know with him. He runs into people and gets talking. How come?”

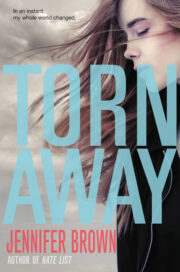

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.