Maybe it was all of the above, but I panicked. My chest squeezed tight and I dropped to my knees on the floor, surprised by the sensation. My hands, which were shaking, clutched at my chest and I gasped and gasped. I could feel my eyes bugging out, but I couldn’t see my grandmother or the carpeted basement steps anymore.

All I could see was the bottom of Ronnie’s pool table, the papers as they blew around me, a rolling ashtray. All I could hear was the collapse of my kitchen down into the basement, the roar of a wind mightier than anyone had seen in forty years, death and destruction balled up inside its nasty, painful grip. I could hear the sound of glass breaking, of bricks thudding to concrete, the squeak of wood splintering. Myself screaming.

Screaming and screaming and screaming, my eyes squeezed shut so tightly I was no longer sure where I was. Only that I felt paralyzed by fear—the fear that began on the day my mom took Marin to dance and never came home again. The fear I’d been holding at bay, had been pushing down inside myself, all through the days after the tornado, through the time at the motel with Ronnie, through those frightening nights of wondering what Lexi and Meg would do to me. The fear washed over me, held me down, made me feel like I was going to die—just lie down and join my mother and sister.

I don’t know how long I remained that way. But eventually, as if coming up from the deep end of a pool and taking my first breath, I began to sense things. My grandmother’s voice, saying my name over and over again, her hands gripping my shoulders, and a movement that sharpened into shaking.

“Jersey!” she was barking. “Jersey, dammit! Stop screaming. It’s going to be okay. Jersey!”

She shook harder and harder and I felt my head moving back and forth on my shoulders, and finally the shrieking just… died out. I blinked through the tears and the swollen eyelids and saw my grandmother kneeling before me, looking stern.

“Stop it,” she said. “Stop screaming. They’ve turned off the sirens.”

My mouth clopped shut, my lips slippery with snot, and I tried to catch my breath.

“It’s all clear,” she said, her voice still barking, but softer now. She’d given me a soft shake on the words “all” and “clear” but then must have seen some recognition that I was back to reality, because she nodded curtly and let go, then stood up. My grandmother crossed her arms and gazed down at me unyieldingly.

“You can’t go disappearing like that,” she said, and I wondered if this sharp-featured woman was the Patty my mom had hated so much. “We were worried sick with the storm coming in. You could have been anywhere. Grandpa Barry is out there right now, driving around looking for you.”

“I didn’t tell him to come find me,” I said, my numb lips barely opening to let the words out.

“You could have gotten hurt. Or worse.”

“Worse,” I repeated, then coughed a dull, mirthless laugh. I felt like I was dying. Or maybe like I would never finish dying. Like I would be stuck in this pain forever. I turned my eyes up to look at her, furious and scared and swinging wildly with my words. “You mean I could have lost everything I ever cared about? Bad news, that’s already happened. Or do you mean worse like I could have died? Because that would actually have been better. I should have died with them. I wish I had died with them.” Somehow, despite my fatigue, I managed to pull myself to standing. “Death would be a blessing,” I said, though I knew I didn’t mean it, and I knew that the words hurt her and scared her. I didn’t care. I was beyond caring. I was so confused and so overwrought and so tired of all of this. What did it matter if someone else got hurt? She could join us—the walking-wounded club.

She softened, tried to reach out to me, but I shrugged away. “Oh, Jersey, you don’t mean that. I know you were close to your mom, but—”

“Don’t talk about my mom,” I snarled, my voice ratcheting up again. “She hated you. She ran away from you before I was born, and she never wanted anything to do with you again. It’s actually a good thing she’s dead, because she would rather die than see me be raised by you.”

My grandmother stiffened, and I was almost certain I saw her eyes go soft and watery, but she kept herself together. “Unfortunately, we’re your only choice,” she said.

“You can’t call it a choice when there’s only one option,” I said. “I didn’t choose. I don’t know anything about you. Because my mom didn’t tell us anything. Marin lived and died with no grandparents, don’t you understand that? Marin never even asked about you, because you didn’t exist to her. So thanks for the ‘choice,’ but no, thanks.”

This time I did see a tear roll down my grandmother’s softly wrinkled cheek, and I was sick enough to feel satisfaction. I even smiled, though inside I knew it was wrong to hurt another person this way. I wasn’t the only one hurting, and my pain wasn’t her fault, wasn’t anyone’s fault. She was just the one getting the blame.

“Jersey, we want to help you,” she said softly. She reached toward me again, and this time I skirted her and headed for the stairs. “We can get you some grief counseling,” she called to my back. “We can get you whatever you need. We love you.”

I stomped up the stairs. Grief counseling. Like that was going to work. Like some New Age bullshit-spouting therapist with “coping techniques” was going to bring my mom and sister back.

“Well, I don’t love you,” I said coldly over my shoulder, not bothering to break my stride. “None of us ever did.”

I slapped the light switch as I reached the top of the stairs, leaving my grandmother in darkness, the same way Meg and Lexi had left me.

CHAPTER

TWENTY-SEVEN

It rained off and on for the rest of the day and into the evening. I could hear my grandparents puttering around the house, doors opening and shutting softly, words spoken too low to make out.

I curled up in my blankets and stared through the window at the gray sky, the raindrops on the glass making funny shadows on my comforter.

I felt awful. I couldn’t help myself. Now that I’d dumped everything on my grandmother, I was consumed with guilt. Partly for hurting her, but also partly because I’d begun to doubt my mother. What if my grandparents weren’t the only ones to blame? What if she’d been hardheaded and hard-hearted, too? I knew it was possible, because I’d barely recognized myself down in that basement.

And what did it matter, anyway? Mom’s fight with them was most definitely over now. Had it been worth it to her? Did she know her parents had come to her funeral? Did she know I was with them now? Did she approve?

I wished so badly I could talk to her, that I could ask her these things.

Under the covers, I shut my eyes and pressed my palms together, waiting for words, but it was like something inside me was afraid to approach my mom, even in prayer. Every time I got close to thinking a direct thought to her, my brain backed away, my heart closed down, my words failed me. Talking to her this way meant she was dead, and I couldn’t go there.

My door opened and the light switched on, making me wince and blink. My grandfather stood in the doorway, which surprised me. Usually it was my grandmother who came to my room. He’d never once come in.

“Grandma went to bed for the night,” he said evenly. “She was upset and had a headache. So if you want dinner, you’re gonna have to make it yourself. Unless you want peanut butter and jelly. I can make that much.”

“No, thanks, I’m not hungry,” I told the streaks of rain on the window. But after he left, leaving the door open behind him, I found that I was actually starving.

It took me a few minutes to work up the nerve to enter the kitchen, where I knew he would be. But there was something about my grandfather that I didn’t mind so much. Maybe it was the cards, but I almost felt a sort of connection with him, even if I didn’t want to admit it. There was something about him that seemed trustworthy. It felt like it had been so long since I’d had someone to trust.

I wasn’t surprised to see him at the kitchen table, playing solitaire. And losing, as usual.

“Three of clubs on two up top,” I muttered as I walked by. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see him pick up the card and move it, while I searched through the cabinets until I found a box of macaroni and cheese. I flipped it over to look at the directions, even though I pretty much had them memorized. It had been so long since I’d gotten to do something as mundane as make myself macaroni and cheese. It felt good, like a routine revisited. I put a pan of water on the stove and turned it on, then leaned against the kitchen counter, unsure of what else to do. “There’s a jack there,” I said.

My grandfather stared at his cards, his hands hovering above them. I stepped forward and pointed.

“Right there.”

He moved the cards.

“Why do you keep playing that game?” I asked. “You always miss the cards.”

“Oh,” he said, pulling three cards out of the deck in his hand and flipping over the last one, “I suppose I think it’s keeping me mentally agile.” He glanced up, winked at me. “Imagine how many I’d miss if I didn’t play.”

I couldn’t help giggling. “You’d miss none. Because you wouldn’t be playing.”

“Huh,” he said, acting as if he were pondering. “I guess I wouldn’t, would I? Or maybe I’d miss them all. Care to join me? We can play Spit.”

I grinned. Spit was all about speed. No one had ever beaten me at Spit. Once, I’d even made Marin cry during a game of Spit, it was such a slaughter. “Deal me in.”

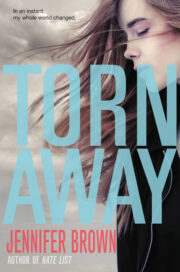

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.