But that was the problem. I had so much going on in my heart, and it didn’t often go together or make sense or even stay the same from moment to moment. How did I speak from a heart that didn’t understand itself? What did I say?

When the garage door rattled open, I was surprised that an hour had gone by so quickly.

My grandmother came in and for a moment just stood and watched our game, her light-brown old-lady purse dangling from her wrist, a pair of giant sunglasses on her face.

“Lunch?” she finally asked, peeling the glasses from her face and setting the purse on the counter.

“You betcha!” my grandfather cried, laying down his cards to win the game. I slapped down my remaining cards in frustration. “My belly button’s rubbing my backbone.”

“No, thank you,” I said. “I need some fresh air.”

I could see it, the bewilderment, as it crossed her face. Surely she had come in and seen me playing with him and thought I’d turned some big corner. Maybe she even thought this was the mark of a great beginning for us. A breakthrough.

But it was too much. All of it was too much. I didn’t know what I was feeling, but I knew I needed some time alone, some space to think about everything.

CHAPTER

TWENTY-FIVE

The day had turned sort of cloudy but was still warm. Someone nearby was mowing a lawn and I breathed in deep as the scent of lawn mower, gasoline, and cut grass reached me. The smell made me nearly double over with memories.

Marin, outside with her plastic lawn mower, following Kolby around as he worked the real lawn mower in lines across his front yard. Her feet were bare in my memory, her toes painted pale pink and glittery. She was wearing a leotard—the one with the ladybug appliquéd to the front from a spring preschool recital—and was singing, though her song was drowned out by the noise.

Mom was kneeling in the flower bed, her hands in a pair of blue-and-gray-striped gardening gloves too big for her fingers. She gripped weeds in her left hand, using a trowel with her right to dig up stubborn roots, while at the same time asking me questions about school.

“How is Jane doing?”

“Fine. She got some award at the Model UN thing last weekend.”

“Oh, wonderful! Tell her congratulations from me. What about you? What do you have coming up?”

“Not much. Drama club is doing monologues. Dani’s performing a scene from Alice in Wonderland. You should hear it. It’s really good. She made Mrs. Robb cry.”

“What play is yours from?”

“I’m just doing the lighting. I don’t have to do a monologue if I don’t want to.”

“Oh, but why don’t you?”

I was drinking lemonade Mom had made that day because she’d gotten off work early. She’d even bought fresh raspberries—something we couldn’t often afford—to sink in the bottom of the glass. The front door was open, the house dark behind the screen. Everyone was outside, playing or working, soaking up the cool early-evening air.

It was the best. It was a random day and could have been swapped with so many other days that were similar to it, yet it was the best.

And now I was walking through a strange neighborhood, alone, knowing I would never be outside with Mom, Marin, and Kolby again. I passed several neighbors, who all seemed to be eyeing me funny, and wondered how many of them knew my story. In a small town like Waverly, probably most of them did. Stories tended to be the favorite pastime in places like this. Stories about scandal or death or destruction even more so. And my story had all of the above.

Is that Patty and Barry’s granddaughter?

Oh, yes, I’m sure it is. That ungrateful Christine’s daughter, I suppose.

So-and-so told me she lost everything in that awful tornado up in Elizabeth. Can you imagine?

Poor thing. If her mama had stayed here…

I felt icky under their stares, but I also wasn’t sure if I was imagining them, so I pointed my face down and kept walking.

I’d gone a good ways, and had a good ways to get back to my grandparents’ house. Not that I was eager to get there, but I’d noticed that the sky had continued to darken, and now the faint rumbling of thunder sounded off in the distance, hastening my heartbeat. A storm was coming. How could I have not noticed when I left?

The wind began to pick up, the hair of the little girls playing ball whipping around their faces. They yelled louder to be heard over the wind as they played.

I checked the sky. The clouds seemed to be tumbling and roiling, blocking out the sun and making me feel cold inside. There hadn’t been a storm since the rain stopped two days after the tornado. I had never been afraid of storms before, but I found my pace quickening, my breathing getting deeper as I lunged down the sidewalk, hoping to get back to the house before the storm really rolled through.

This wasn’t me. I kept thinking that as I felt my limbs shaking, my brain filling up with panicky thoughts. I didn’t even know who I was anymore, and it hurt to feel myself changing. I wanted my life back. I wanted so much that I couldn’t ever have, and everything felt so horrifically unfair and frightening and sad, it took all I had to keep control. I felt like I was slipping away.

The thunder got louder and more frequent. I could see them. I could see my sister and mother, backing away from the windows at Janice’s studio. I could hear the little girls crying, could feel the phone buzzing in my mother’s pocket as I called her. I could see my mom, holding the phone to her ear, shouting, telling everyone to get back, unable to hear me on the other end of the line.

I could see them, hand in hand, sprinting across the street to the grocery store, ushering the little girls along in their sparkly leotards and their tightly bound updos. I could hear the girls’ frightened voices, could smell the electricity in the air, could feel the sirens bleating through their bodies.

I could see them, eyes going wide as the tornado became visible, and then squinching down tight as debris and cars and streetlights and entire roofs looked like dots of litter in the sky, before crashing down onto the streets.

I could feel them, fear sinking in—fear and the instinct for self-preservation—as they thrust themselves down the aisles at the grocery store, hoping to get far enough.…

I reached the end of the street and turned the corner to get back to Flora Lane, picking up to a jog, and then a run as raindrops—pregnant and insistent—began to beat down on me. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the ball the kids had been throwing earlier, bouncing in the wind down the center of the street.

It had gotten so dark. So very dark.

I pushed myself harder. My stomach hurt from exertion and panic. My grandparents’ house still seemed so far away.

And then I skidded to a stop, gasping and pressing my palms hard over my ears as the tornado alarm started sounding.

CHAPTER

TWENTY-SIX

My grandmother was standing on the front porch, one hand holding the top of her head as if she were afraid her hair was going to fly off. Her face was deeply lined with worry as she glanced at the sky and then moved her eyes up and down the street. She called my name twice before she saw me, half-jogging, half-staggering along the sidewalk, hands over ears, ragged breath tearing dry tears out of me.

I didn’t want her to be a beacon of safety for me. I didn’t want to feel like I was running home while running to her. But my heart leapt around in my chest when I saw her.

“Jersey! There you are,” she said, and I could barely hear her over the siren. “I was worried.”

The rain began to splatter around me as I cut through the front yard, my legs feeling exhausted and jelly-like as I pounded one foot in front of the other. For a terrifying, almost dizzying moment I was afraid I’d be unable to make it those last few steps. I was sure my legs would give out and crumple beneath me, that I would sprawl facedown in the grass, my grandmother unable to pull me up. I imagined the sky splitting open and an angry tornado reaching down to scoop me up and toss me into its eye with flying debris and swirling dead people; people like my mom and sister.

But somehow I made it, and even though my grandmother was reaching out to me, I lunged right past her and into the house. I raced through the hall and down the basement steps without even pausing to search for the light switch, my brain briefly flashing back to the day Meg and Lexi had shut off the basement light and I’d gotten so spooked. The memory only served to agitate me further, and I could feel fury rushing through me.

Down in the basement, it was quieter. The sirens were muted and the wind was no longer beating in my ears and the rain sounded far away up on the roof. Still, I was buzzing. My head was making a siren noise of its own. My ears were ringing and my breath panted out of me as I paced, moaning and crying and growling. I didn’t know what was wrong with me. I’d never felt or acted this way in a storm before. But I couldn’t stop it. I couldn’t stop the fiery, tossed feeling in my chest, and I couldn’t stop my body from acting on it.

“Jersey?” my grandmother called, and seconds later the basement was bathed in light. I saw her feet pad down the carpeted stairs. “Jersey? Can you hear me?”

And maybe it was the way she kept saying my name—always, constantly, saying my name—or maybe it was the fear or the siren, which had gotten into my head. Or maybe it was those words—“Can you hear me?” Those words that I had said to my mother a few weeks before. Those words, which had gone unanswered.

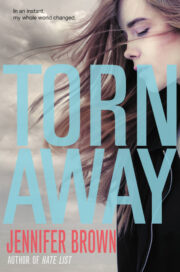

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.