She argued. He felt some satisfaction in watching her head come up and in knowing that she was not reacting with that meek, downward glance that she had affected with the Barries. But the show of spirit did her no good. He did not hear what she said. He was sorry, the innkeeper said with an exaggerated and careless shrug. What did she expect him to do? Call out the carpenters and make another room just for her ladyship? She disappeared upstairs after a few minutes trailed by the maid, who first turned and gave him a saucy look. Yes, she was Effie, obviously.

Strange! The woman he would have bedded last night was to share a bed with the female he had intended to make sport with tonight. Why should he feel indignation on behalf of Miss Moore, when he had judged both females desirable enough to lay their heads on the pillow next his own?

The Earl of Rutherford rose to his feet, stretched, and made his way unhurriedly to the staircase.

Jessica was sitting miserably in the taproom, trying to convince herself that she did not look as conspicuous as she felt. There was no separate dining room in the Blue Peacock. There were a few private parlors, she gathered, but of course those were very private. She was forced to take up a position in the common taproom, and there she must stay until it was bedtime. Even then she could expect no privacy or comfort. She must share the untidy and none too clean attic room of the maid, who made no bones about her reluctance to extend such hospitality.

She longed suddenly for her room at Lord Barrie's house. At least it had been her own and only rarely invaded by Lady Barrie come to scold her for some imagined offense or by Sybil intent on wheedling her into doing some task for her. She had not been treated well during the two years of her employment, but at least she had known where she belonged and what to expect. Here she felt conspicuous in her quietness. Her female companion of the coach was seated at an adjoining table, laughing raucously and tipping back a tankard of ale just like the men.

She looked up in some surprise at the sound of a discreet cough beside her. The Earl of Rutherford's valet stood there, looking as immaculate and toplofty as he had looked for the past week as he lorded it over the Barries' servants.

"His lordship 'as begged me to hinform you, ma'am," he said, having the grace to speak quietly, "that 'e would be hobliged to you for joining 'im for dinner in 'is parlor."

Jessica felt the color rise in her cheeks. He was here? And knew that she was here too? And he wished to entertain her? Alone, in a private parlor. He must know the impropriety of the suggestion. Of course, she was merely a governess, a servant. She looked around the room and reminded herself anew of the alternative.

"Thank you," she said, and rose quietly to her feet. She allowed the valet to lead the way across the crowded taproom and up the stairs. Her heart was beating with painful thumps by the time he opened one of the doors on the upper story and stood aside for her to precede him into the room.

The parlor was empty, she saw with great relief. What on earth was he doing at this inn? She had heard nothing the day before about his intention to leave.

It was a comfortable room, not large, but made cozy by the worn carpet on the floor, two shabby armchairs, a table already set for two, a branch of lit candles on the table, and a cheerful fire crackling in the hearth. Jessica crossed to the fireplace and held her hands out to the blaze. She had not realized just how much the cold had contributed to her misery during the day's journey and her short stay in the taproom. The valet had disappeared through a second door.

"Ah, Miss Moore,"the voice of Lord Rutherford said from this inner doorway a few minutes later. "What a happy coincidence that we have chosen the same inn for tonight. I trust you have had a comfortable journey today?"

He looked larger, more overpoweringly masculine in this small room than he had looked at Lord Barrie's. There was a certain haughtiness in his manner that only succeeded in making him look more handsome than usual.

"Yes, I thank you, my lord," she said.

"Liar, Miss Moore." He smiled and advanced farther into the room. "I have traveled on the stagecoach in my time. It is considered one of the necessary experiences of life by young blades, you know. There is no more disagreeable mode of travel. Especially, I would imagine, if one were forced to ride inside, as you must have done. Was the company enlightening?"

"Not especially so," she admitted, unsmiling. "But at least I was out of the rain for the last hour."

"And your accommodations are comfortable, I assume?" he asked politely.

"Yes, quite, I thank you, my lord," she said.

"You are accustomed to sharing a room and a bed with barmaids, then?" he asked, eyebrows raised.

Jessica's lips tightened. "I perceive you are in the habit of asking questions only so that you may contradict the answers," she said. "I have not complained, my lord. My purpose is to reach London as soon as I may. I do not demand luxuries along the way."

"And do you have some bright prospect ahead that makes you rush so, Miss Moore?" he asked. "I was unaware that your departure from your employment with the Barries was imminent."

Jessica did not answer.

He closed the remaining distance between them and stood before her. "Does your presence on the road to London have anything to do with me, Miss Moore?" he asked, hands clasped behind his back.

"My lord?" She looked up at him with wide, blank eyes.

"My lord?" he mimicked. "All innocent incomprehension, my dear? I am asking you if you were dismissed from your employment?"

Jessica's head dropped until one long aristocratic finger came beneath her chin and raised her face very firmly so that she was looking at him again.

"Of what are you accused?" he asked. "As I remember it, we were not even touching when we were so unfortunately disturbed. Not that I would not have had matters otherwise if I had had my way. Surely it must have been obvious to common sense that if we had been in the process of enjoying each other, we would not have been standing in the library, almost respectably clothed."

"In my employment I was not permitted to have any dealings with male guests," Jessica said.

" 'Dealings,' " he repeated. "Standing in the library very properly repulsing the advances of a male guest was construed as having dealings? My poor Miss Moore. I am so dreadfully sorry. I had no idea. Even when I left this morning, I was quite unaware that you had been called to account and sent packing."

Jessica wished he would remove his finger from beneath her chin. She was finding looking into his eyes very uncomfortable. "You do not owe me an apology, my lord," she said. "What happened was not your fault. I have been in trouble before for leaving my room after retiring for the night. It was not your fault that I was in the library when I had no business being downstairs at all."

He looked searchingly into her eyes for a moment but was prevented from commenting by the arrival of the innkeeper with their dinner. He released his hold of her chin and gestured toward the table, where he seated her with marked courtesy. The landlord too, she noticed, bowed in her direction after filling her wine glass.

Jessica enjoyed the meal far more than she would have thought possible. The food was good, though plain. But it was not that that caused the enjoyment. She was not, truth to tell, hungry after a day of being squashed and jostled on the road. But she found the stiff courtesy of the valet as he served them soothing to her bruised pride. And she found Lord Rutherford an interesting and surprisingly charming host. He set himself to entertain her conversationally and did so, taking upon himself the whoie burden of introducing and developing various topics.

She realized at the end of the meal that he had succeeded in setting her entirely at her ease. And that was quite a feat when one considered that she was dining alone with a man whose attractions had been doing strange things to her heartbeat for all of a week. And how improper it was to be sitting thus with him, un-chaperoned in the private parlor of an inn! But really, she thought as she folded her napkin at the end of the meal, she did not care.

Lord Rutherford had settled back in his chair, one forearm resting on the table, playing with the stem of his empty wine glass. He was looking at her in such a way that she knew that the courtesy a host owed his guest during a meal was at an end. There would be no more purely social conversation, she thought with some regret.

"What are your plans, Miss Moore?" he asked.

Jessica smoothed the cloth before her on the table. "I shall move on to other employment," she said with a shrug.

"As what?" he asked. "I do not imagine the Barries have given you a glowing character reference with which to dazzle a future employer."

"No," she admitted after a short pause during which she could think of nothing else to say.

"You cannot be a governess, then," he said quietly, "or a lady's companion. Or a librarian. Or even a lady's maid. Probably not even a scullery maid. Do you have a family to which to return?"

"No," Jessica said after a moment's hesitation.

"I see," he said. "Your options are alarmingly few, are they not, my dear?"

"I am not worried," she said, lifting her chin and looking him in the eye. "Something will turn up."

"Probably," he agreed. "In fact, Miss Moore, I am in a position to offer you employment that is well paid and would place you in a positon of some security and some comfort."

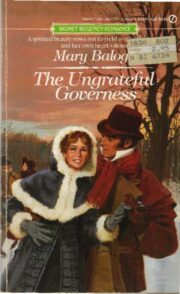

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.