"Some persons do like to put on airs," the male agreed with a wheeze. "Prob'ly used to traveling around in their private coaches where they can spread out all along one seat and stretch their feet on the pposite one."

"Nobody better not try to put their feet on this seat," a passenger of superior wit across from them said. "Not unless they wants ter walk on stumps that begins above the ankles for the rest of their born days, that is."

Jessica was further squeezed by the hearty laughter of her neighbors. She wisely chose to ignore all remarks and won a sniff and a charge of being "uppity" from the female beside her for her pains.

She had found him powerfully attractive from the day of his arrival. As who would not? she asked herself. The Earl of Rutherford was a good-looking man by any standard: tall, athletically built, his aristocratic features, very dark hair, and blue eys designed by heaven to make any normal female heart skip a beat. To a lonely, love-starved young lady he appeared quite irresistible.

She had rarely been in the same room with him, had never been closer to him than the width of a room, had spoken not a word to him. He had not even noticed she existed, she had believed. But she had looked when no one was observing her, and what she saw had filled her with longing, the longing for pretty, flattering gowns, for wearing her hair about her face, for the freedom to smile and lift her eyes to the world. She had longed for one of his looks, one indication that he knew she existed, one sign that he knew she was a woman.

She had been kept severely in the background. Even her usual task of chaperoning Sybil during visits and walks was usurped by the girl's middle-aged abigail. She had been sent back to her room one morning when it was judged that her hair was not tightly enough pulled back and some wave remained.

She had not expected him to notice her. Indeed, she had not thought he would stay long. He had come there by some chance as a prospective suitor for Sybil. It seemed unlikely to Jessica that he was as firm in his intentions as Lord and Lady Barrie seemed to believe. Such a man would have no trouble at all finding a wife. Even if his pockets were to let, he could surely find a more amiable wife among the ranks of the wealthy than Sybil. Jessica did not believe that in two years she had made any impression on the girl's character whatsoever. She was as bad-tempered, as selfish and uncontrolled now as she must have been from childhood. And she had no beauty with which to blind a suitor to the defects of her character until after a marriage had taken place.

But he had been there a whole week, and he had noticed her. He had even known her name last night. Of course, he had noticed her in one way only. She was a governess. A servant. And apparently presentable enough in her nightgown and with her hair down to be deemed worthy of a night in his bed. There was nothing remotely flattering about such notice.

But oh, she had been tempted!

He had looked quite suffocatingly masculine, dressed as he was only in his breeches and a silk shirt open at the throat. His hair had been tousled, as if he had just risen from his bed. And those blue eyes, seen at close quarters, had been disturbingly direct.

She had felt almost instant desire. She had wanted to be held against that tall, strong body. She had wanted his hands and his mouth on her. And truth to tell, she had felt her knees weaken at the thought of going to his bedchamber with him and allowing him any intimacy that he chose to take. Virtue, chastity, virginity had seemed dreary taskmasters for a few mad moments. She had had but to say the word. She could have experienced delights to dream of for a lifetime. He had assured her that he was skilled, that he liked to give as well as receive pleasure. And she had not doubted him for a moment.

Why had she held back, then? Why had she denied her own desire, her own deepest need? Perhaps it was just the knowledge that what for her would have been the experience of a lifetime would have been merely the delight of a moment for him, something he would have forgotten after a few days and the next woman. She had found when it came to the point that she could not degrade herself to that extent. She could not allow herself to become what all men seemed to expect female servants to be: ready bedfellows. Not persons at all. Merely the human instruments through which they could satisfy their sexual appetites. She could not do it and live with herself the next day.

But she was not at all sure, Jessica thought, sighing inwardly as the large female changed position and jostled her further with hip and elbow, she was not sure at all that she would be strong enough to make the same decision if it were hers to make all over again at this very moment. It would be something indeed, something worth having, to be granted just a few minutes out of a life of neglect and insult in which to be the full focus of a gentleman's attentions. To know that for those minutes he would be intent only on her, on both pleasuring and being pleasured. To be seen fully just once, wanted fully.

But wanted for what? For Jessica Moore? Or for the woman's body in which Jessica Moore just happened to be housed?

She shifted sideways so that some of the pressure was taken off her left arm at least. She wondered how far they had traveled and how much farther they would travel that day.

2

The Earl of Rutherford cursed aloud as he turned his curricle into the cobbled yard of the Blue Peacock. It looked to be a large enough inn, but he had never heard of it before and had no way of knowing if it was worth his patronage. Besides, he had a feeling that the stagecoach he had passed an hour before must use this particular inn as a stopping place. There seemed to be nowhere else of any size to rival it. And darkness would be upon the coach by the time it got this far. He did not relish the thought of spending a night amid the noise and vulgarity of stage passengers.

He had hoped to travel much farther himself that night, but the rain that had begun half-heartedly a while earlier was now setting in for the night and was becoming something of a downpour. And the coolness of the November day had turned to an uncomfortable chill. It would be madness to continue on the road in an open curricle. Apart from the personal discomfort of raindrops dripping from the brim of his hat and somehow finding their way down his neck, the vehicle was not solid enough to cope with muddy roads. At least a heavier carriage could be relied upon to stick fast and safe. A curricle would slither and slide until it overturned into a hedgerow.

Even the Blue Peacock offered a less unpleasant prospect than that. Rutherford vaulted from the high seat of his vehicle, handed the ribbons to a lackey, and strode into the dark but blessedly dry taproom of the inn.

He was feeling somewhat reassured ten minutes later, having found that the inn was as yet empty of guests with the result that he had been allotted the best room in the house and, he suspected, the only good one, a bedchamber complete with private parlor. His rooms were clean, he had discovered, the mattress dry and reasonably free from lumps, the sheets clean, and the maid, whom he had passed on the stairs, a potentially satisfying armful.

He did not have a great deal of baggage and was quite unsure if his valet would catch up to him with the carriage that night. But no matter. All he really needed was a change of shirt for the morrow and his shaving gear, both of which he had in his leather bag. He never encumbered himself with a nightshirt on his travels for the simple reason that he did not wear one. He had never found that his companions of the night objected to the lack.

Lord Rutherford toyed with the idea of ordering his dinner to be brought to his parlor immediately, but he decided that it was too early. He had eaten luncheon only a few hours before. But what was he to do with himself? He did not have so much as a book in his bag. He could not take a walk as the rain was now streaking down outside. He would go down to the taproom, he decided, and look over any new arrivals. And the innkeeper had seemed like a garrulous fellow, who might have some interesting stories. Innkeepers were rarely bores, he had found from experience. They had seen too much of the quirks of human nature ever to run dry of an amusing or sensational anecdote. And that buxom maid merited a second look. She had signaled her availability in that moment of passing on the stairs. The decision would be entirely his.

Rutherford was soon settled in the chimney comer, a pint of ale on the table at his elbow, the coals of the fire setting his damp breeches to steaming. Three new arrivals were seated at their ale exchanging loud banter with the innkeeper. The maid had whisked herself in and out of the room a couple of times, entirely for his benefit, Rutherford judged in some amusement, although she preened herself over the ribald comments of the newly arrived trio. He might decide to take his pleasure with her later. There would be no unusual satisfaction in doing so as she was the unsubtle kind of female. But she would at least help pass what promised to be a long and dull night.

His mind went back to that morning. His abrupt leavetaking had been somewhat embarrassing as it had been patently obvious to him that both Lord and Lady Barrie had expected a declaration. Fortunately, he had not seen their daughter before leaving, though doubtless she shared their expectations. She had been treating him with a markedly proprietary air for two or three days past. In fact, right from the start they had all behaved as if he had come as a formal and recognized suitor.

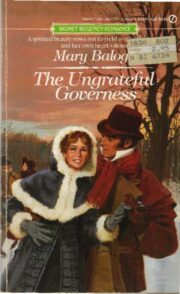

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.