He grinned briefly into his tankard of ale. Life with that particular young lady did not bear contemplation. No beauty. No character. No sweetness of disposition. He pitied the poor man who would finally be ensnared by those three determined persons. His life would not be worth living. And someone would surely be caught. The one desirable attribute the girl had-and for many it would far outweigh all the less attractive ones-was money, and lots of it.

Thank the Lord he did not have to marry for money. He wished he did not have to marry at all. But he had heard nothing else since his nine-and-twentieth birthday had slipped by him eight months before and the dreadful prospect of the thirtieth loomed ahead. It was his duty, it seemed, to plant his seed in some as yet unknown female of suitable background, whom of course he would first have to make his wife. It seemed that a man was likely to pop off at any moment once his thirtieth birthday was behind him. And the best way to protect himself against the imminent danger was to beget some other poor male creature who would be all ready to step into his shoes and his title until he too had the misfortune to find himself in his thirtieth year. It was quite unthinkable to contemplate letting the title pass to a cousin, it seemed, however blameless and worthy he might be.

His parents had been at him, Mama with her quiet smiles and assurances that matrimony was a blessed state, Papa with his reminders that it was not only the title of Rutherford he must safeguard but also his father's of Middleburgh, a dukedom no less. Faith and Hope, his sisters, had added their word-or words would be more accurate, he thought with a grimace. Hope, always an eager matchmaker, had redoubled her efforts during the last year.

And yet again, irrelevantly, he blessed the kindness of fate that had made him, the third child, a boy. Not that he craved the titles, which of course he would not have received had he been a girl, but he would have detested having to go through life as Charity. His mother, he had heard since, had been divided in her feelings at his birth. She was proud and relieved to have produced a son and heir at last, but she did regret the incomplete Biblical trio. They had called him Charles, but he had heard his mother lament the fact that Faith, Hope, and Charles had a decidedly anticlimactic ring to it. A third daughter never did arrive.

His grandmother had been the final straw. He had been in the habit of visiting the dowager duchess at least once every two weeks through all his boyhood and the years since, except when he was at school or university, of course. And he had always enjoyed a good relationship with the old girl, he had thought. She admired backbone in a man, but approved of his sowing his wild oats during his early manhood. He had always been remarkably open with her-far more open than with any other member of his family-about those oats. However, he had realized only within the past eight months that although she recognized the importance of wild oats, she also valued cultivated oats and believed that they were the ones that mattered and must take precedence over the weeds. She had ceased to chuckle over his exploits during those months and had developed the habit of harping on duty.

His duty! He must marry and impregnate his wife on his wedding night, it seemed. His grandmother did not put matters with quite such open vulgarity, of course, but that was what she meant, He had been evasive for months, but just three weeks before he had lost his good humor and pointed out to her in no uncertain terms that there was not a single lady of his acquaintance with whom he could possibly contemplate a life sentence. He would just have to gamble on living a few years longer yet and postponing that comfortable arrival of his heir.

His grandmother had called him a humbug. At least, she had called her needlepoint a humbug, which amounted to the same thing, as the stitchery could have done nothing to offend her.

"Very well, Grandmama," he had said rashly, "you name me an eligible lady and I shall go immediately and look her over. Offer for her too if I don't turn green at the prospect."

"Ella's granddaughter," she had said without a moment's hesitation, speaking of one of her card-playing cronies. "In the country. Coming up for the Season next spring, but bound to be snaffled up in a twinkling, Charles. Father loaded with the blunt. You go down there and forestall the opposition. Good family. Barrie. And just out of the schoolroom. Don't tell me that fact don't set your mouth to watering, m'boy, for I shan't believe you."

"You have not even seen the girl, Grandmama?" he had asked, aghast.

"Don't need to," she had said. "She has everything you could want in a wife, Charles. Haven't heard anything about her being unable to breed. That's all that matters, y'know. You don't need to give up all your high flyers, boy. Always used to tell Middleburgh he might have one for every day of the week as long as he kept up appearances. Didn't want him forever hanging about my skirts, anyway. A devilish nuisance, men. No offense, m'boy. What?" she said, looking up at him from beneath her eyebrows, her head still bent over her needlepoint. "Afraid?"

"When do you wish me to leave?" he had asked, knowing even as he did so that there was no way of reneging on his rash challenge now.

And so he had spent an unspeakable week with the Barries, wishing every moment to be on his way back to London again, but staying for courtesy's sake. But a week was the limit, he had decided the night before after that fiasco with the governess. He would return to Grandmama and insist that he had kept his part of the bargain. He had looked the girl over, found that he did indeed turn green at the prospect of offering for her, and so had come home without doing so.

What a waste of a week, he thought with a yawn, nodding in the direction of the innkeeper and indicating that he wished to have his tankard refilled. The only event that might have made it at all worthwhile would have been a night spent with the gray governess. She had turned out to be even lovelier than he had suspected all week. That hair! He almost regretted that he had not stolen a kiss and drawn her body against his own. He suspected that it was very feminine and very shapely indeed. A night with her would have been rare sport.

However, he had got very little for all his imaginings. Unfortunately, he was afflicted with a conscience that made it impossible for him to take even as much as a kiss from an unwilling wench. Under the circumstances perhaps it was as well that nature had framed him in such a way that he did not often encounter unwillingness. On the contrary. On occasion he had even found himself obliging eager females when he would just as soon not have done so, merely because he did not wish to hurt their feelings. But if a female did say no, he had a lamentable tendency to take her at her word. He had to want her very badly even to try a little further persuasion.

Perhaps it was not an unfortunate trait of character, he decided on second thought. He hated the idea of rape. At an all-male gathering several years before, when he had been very young and considerably more foolish, he had broken a fellow's nose and a quantity of crystal glasses and decanters after the man had recounted with pride for the noisy delight of most of his listeners how he and two other daring blades had held down and ravished a lady's maid as she sat waiting for her mistress in a carriage outside a house where a masquerade ball was in progress. The crowning glory of the tale was the fact that the girl had been virgin and was dismissed three months later for being with child.

Lord Rutherford's hand paused halfway to his mouth. Sure enough, the sounds coming from outside in the cobbled yard could be produced by nothing other than a stagecoach. Very soon now his peace would be shattered by the spilling out of the human contents of that coach. He would finish his ale and retire to the relative quiet of his parlor. It really was going to be a long evening. He would have to avail himself of the services of the maid. Though she was likely to be busy about her chores until late into the night.

He watched the passengers make their noisy entry. Two young sprigs of fashion who had been riding on the roof looked more like drowned rats than the dandies they wished to be taken for. They were both slapping their hats against their legs and shaking their greatcoats, talking and laughing loudly to try to compensate for their less than immaculate appearance. Two females, one thin and one fat. Two males to match. Another man all in black, who looked as if he might be a Methodist preacher. And Miss Moore.

Rutherford's eyebrows rose and he set his tankard down slowly on the table beside him. She did not look around her. She stood quietly a little behind all the other passengers, who were loudly jostling for place and clamoring for rooms. She was clutching a worn valise, her beauty and her form completely swallowed up in gray again. She was turned fully away from him so that there was no chance of her seeing him even out of the corner of her eye. She waited for her turn with the landlord.

He could not hear what she said, even though by the time her turn came most of the other passengers had gone off to their own rooms. But he did hear the landlord's reply quite clearly. There were no rooms left. He was sorry. He sounded far from sorry, Rutherford thought, a different man entirely from the genial and subserviant host who had welcomed a fashionable earl an hour before. She must sleep in the taproom or share Effie's bed. The choice was hers. It was all the same to him. The cost was the same, whichever she chose. Effie was the maid, Rutherford guessed.

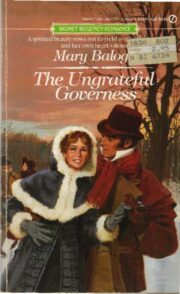

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.