He took a rueful half-step backward. There were, of course, always those few gray creatures who were so from choice, whose virtue was unassailable. A great shame in Miss Moore's case as she was a rare beauty even clad in the unbecoming and virginal nightgown. She would have been far more satisfying in his bed than any of the books ranged behind her. And a far more effective sleeping potion. He moved his hand forward until it held only the one lock of hair again.

"You need put neither your lungs nor your employment in jeopardy," he said. "I have never been driven to rape any female, Miss Moore. I see no reason to begin on you. I foresaw an hour's mutual pleasure, that is all. You are quite free to step around me and leave, your virtue intact. My apologies if I have wounded your dignity."

He grinned down at her and let his hand rest on her shoulder for a moment. He was about to step back and sweep her a mocking bow. He anticipated the only pleasure that was to be granted him that night, it seemed: that of watching her cross the room with her indignation and her bare feet, knowing herself watched.

The next person to enter the room was clearly less intent than he had been on not disturbing the house. And the sight of two candles within did not set the new arrival to withdrawing quietly as he had begun to do earlier. When the door opened, it did so quite abruptly and noisily, and its sound was succeeded by the immediate entry of Lord Barrie, a whole branch of candles in his hand.

Lord Rutherford turned toward him, one eyebrow raised. "Three of us suffering from insomnia, Barrie?" he said. "I only hope that you have enough good books to satisfy us all. What would you recommend?"

And he was not even to be granted the pleasure of watching the governess withdraw, he thought with an inward sigh, as she muttered something indistinct and disappeared from the room while he surveyed the shelves languidly and hoped that his host was not about to be his usual garrulous self. Not at an hour well past midnight. And not at a moment when he was still smarting from a strong dose of sexual frustration.

Jessica Moore took one last look around the room that had been hers for the past two years. She knew there was nothing left inside drawers or wardrobes; she had just double-checked those. There was nothing lying on surfaces either. She had everything, then, stuffed inside one small trunk and a valise. One did not accumulate much as a governess. She had arrived two years before with scarcely less than she had now.

There was not much in the room to make her wish to linger. It was a small box of a room on the floor above the family bedchambers, next to the schoolroom. It was too cold in winter, too hot in summer. Facing north as it did, it was never brightened by the direct rays of the sun. Its curtains and bed hangings were an uninteresting shade of pale brown. There was almost no hint left of the floral design that had brightened them in the long ago days when they had hung in a more important bedchamber.

The only thing that made her at all reluctant to leave was the fact that this room had been her only refuge for a long time. The only place where she could go to avoid Sybil's petulant moods, to escape Lady Barrie's waspish temper, to recover from the frequent insults that as a servant she must endure meekly.

Was she sorry to be leaving? She thought not. She had never been happy in this house. Not nearly so. She had no friends, except perhaps the vicar's wife, who was more than twenty years her senior. The servants were awkward with her; the family despised her. And she had outgrown any usefulness she might once have had when Sybil had won a shrill argument with Lord and Lady Barrie a few months before and been officially released from the schoolroom. Jessica had expected to be given notice. Instead, her role had been converted to that of "companion." That is, she was expected to trail around after Sybil, a silent and virtually invisible shadow.

She wished now that she had resigned of her own free will. At least then she would probably have been given a letter of recommendation, even though she would have expected no warm praises from Lady Barrie. But she had procrastinated. Unhappy as she was, at least she was familiar with her situation. The thought of having to start all over again in a new household had filled her with dread.

Well, Jessica thought, dragging the trunk across the floor to the door of her room, she did not have to worry about any such thing now. Dismissed without any period of notice whatsoever and without any recommendation. There was no earthly chance of finding herself another situation. And what was she to do? A wave of panic grabbed at her stomach as she tied the ribbons of her gray bonnet beneath her chin and drew on her gray cloak.

What was she going to do?

She was to leave on the stagecoach to London in one hour's time. But why she had chosen London she did not really know. What was there there for her? But what was there anywhere for her? The stagecoach went to London. That was why she was going there probably. Two days she would have on it. Two days in which to decide what she was to do with the rest of her life. And she could not hope for employment as a governess or companion. Even as a lower servant she would doubtless need a character from someone. And who was there who would be willing to speak for her?

Really, Jessica thought, the panic threatening to overwhelm her for the moment, there seemed to be only one avenue open to her. And she would not take that. Could not. Her pride was far too great. What was she to do?

She picked up her valise with a resolution she was far from feeling and left the room without a backward glance. She would ask Terrence to bring down her trunk. He was the only footman-the only servant, for that matter-who had ever shown her any warmth of feeling. He would carry it for her. She could not expect any sort of farewell from anyone, of course. She was leaving in disgrace. She had not even been granted a maid to help her with her packing. Besides, it was too early for the famiy to be up yet. Lady Barrie had probably returned to her bed after summoning her very early that morning in order to dismiss her.

And probably he was not up yet either, for he had had a late night.

A little more than an hour later Jessica was seated in the stagecoach between two large persons, one male and one female, both of whom were displaying their disappointment at her late arrival to take the empty middle seat by ignoring the fact that she was there at all. Not that she wished for their conversation. But it would have been far more comfortable if they had at least acknowledged her need for room on the seat. She resigned herself to two days of discomfort. Indeed, she must enjoy these two days. At least while the journey lasted she belonged somewhere. Her meager resources would not keep her for very long in London. She had had to pay for her own ticket on the stagecoach.

Had he asked that she be dismissed? Jessica wondered. Did he even know that she had been? She had expected it, had lain awake all night wondering what her punishment would be and fully expecting that it would be dismissal. After all, this was not like the time when Lady Barrie's brother had kissed her beneath the mistletoe while his wife and all the rest of the family had looked on, laughing merrily. Her punishment that time had been merely nine days confined to her room and the schoolroom abovestairs until the visitor she had enticed with her wicked ways had finally taken himself and his wife home.

This was different. This time she had practiced her wiles on the intended husband of Sybil. There could be no forgiveness for such a heinous crime, even after a suitably harsh punishment. A suitor had arrived from London, and the suitor was to be converted into a betrothed and a husband with all due speed so that Sybil could have the great distinction of being a countess at the age of seventeen. Despite the extreme plainness of her face and figure and despite her petulant and bad-tempered nature. No governess was to be allowed to distract the attention of the suitor.

And so she had been verbally abused early that morning by Lady Barrie, called whore among other insults, and told that she might take herself away from the house within three hours. She was not invited to speak a word and indeed did not attempt to do so. She had stood quietly before her employer, looking her calmly in the eye, a daring action that had only stirred the other into further wrath. Servants were expected to direct their eyes at the floor when Lady Barrie condescended to speak to them, like Moses, afraid that the light from the Godhead's countenance would blind them if they looked into it.

Jessica was too accustomed to her former employer to feel any great anger or bitterness at her treatment. It was to be expected. But what about him, the Earl of Rutherford? Was she angry with him? Did she now hate him? She tested the idea in her mind and came to the conclusion that no, she did not really blame him for the course events had taken. Not unless he had asked for her dismissal, that was. But she did not believe he had. What would be his motive? She had refused to go to bed with him. That would not be of sufficient importance to provoke the Earl of Rutherford into vicious revenge. She could say with some certainty that at least three of the chambermaids would have been only too willing to warm his bed at any moment of the night or day.

"Some persons thinks they can turn up at the last moment and take the whole seat that decent folks has paid good money for," the large female at her left remarked loudly to the large male on her right. She was attempting to locate something in the covered basket she held on her knees.

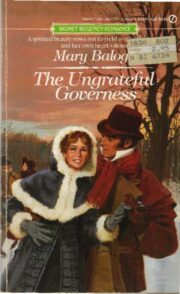

"The Ungrateful Governness" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Ungrateful Governness". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Ungrateful Governness" друзьям в соцсетях.