‘Pray do not distress yourself, ma’am! Pray do not! Very likely he will have escaped, and you will see him presently.’

This suggestion had the effect of stopping Juana’s tears at once. She said indignantly: ‘Escaped! That he will never do, I assure you! My husband is Major of Brigade, and if you were at all acquainted with him, you would know that while a man of ours is not accounted for my husband will not be found out of the saddle!”

He coloured, and turned away his head. After a moment’s pause, he said awkwardly: ‘I daresay you despise me for having left the field.’

She replied candidly: ‘Well, it certainly seems very odd to me.’

‘I am aware of how my conduct must appear to you. But there are circumstances-there are those who are dependent on me-but it does not signify talking, after all! There is Antwerp ahead of us.’

In a few more minutes they had entered the town. The Hussar very kindly offered to find a room for Juana in one of the hotels. She gladly accepted his help, but soon found that there was no accommodation to be had anywhere, the town being already full to overflowing with refugees from Brussels. There was nothing for it but to repair to the Hôtel de Ville, and to try to get a billet. The Hussar went in on this errand, leaving Juana outside with Jenkins and the horses. She was splashed from head to foot with mud; her habit was soaked; and she felt pretty certain from the curious glances cast at her by the many passers-by that she must look a perfect figure of fun. She was past caring for that; all her thoughts were fixed on Harry, and because she was quite worn-out and suffering the most torturing anxiety large tears chased one another down her cheeks.

Suddenly an officer came out of the Hotel de Ville, and stepped up to her where she sat drooping on the Brass Mare’s back. ‘Mrs Smith?’

She looked down at him. ‘Yes, I am Mrs Smith,’ she said brushing her hand across her eyes.

‘My name is Peters. You don’t know me, but I’m on garrison-duty here. Your servant told me your name. You are in such a terrible plight, and there’s no getting you in to any of the hotels: will you let me take you to Colonel Craufurd, the Commandant? His wife and daughters are the kindest people, and would do anything for you, I know!’

It seemed likely that if she refused this offer she would be obliged to bivouac in the street, so Juana thanked Mr Peters, and said she would go with him if she might first take leave of her helpful Hussar-acquaintance. This was soon done, and Mr Peters, bringing up his own horse, led her through several crowded streets to a respectable house not far from the citadel. They were admitted at once by an astonished butler, and received in the salon by a very tall woman, who no sooner set eyes on her muddied, tear-stained visitor than she exclaimed: ‘Oh, you poor little thing!’ and came quickly forward to take Juana’s hand. ‘Mrs. Smith’s husband is Brigade-Major to Sir John Lambert, ma’am,’ explained Mr Peters. ‘She has ridden all the way from the battlefield, as I understand. I took the liberty of bringing her to you, for there is nowhere-’

‘I should think so indeed!’ interrupted Mrs Craufurd. ‘Never mind talking! Ring the bell, man! My poor child, we must get you out of those wet clothes at once, or you will catch your death of cold!’

‘Oh, how kind you are!’ Juana stammered. ‘I am so ashamed to come into your house in such a state! Please forgive! I did not know what else to do.’

‘Why, you’re a foreigner!’ said Mrs Craufurd. ‘As for forgiveness-what nonsense, child! But what is all this talk about a husband? You are a baby!’

‘Oh no, no! I am seventeen years old, and I have been married for three years already! Also I am Spanish.’

‘Spanish or English, married or single, into a hot bath you go!’ said her hostess briskly. ‘Yes, I rang, Johnson. Be so good as to take hot water up to my bedchamber. Don’t stand staring, man! Bustle about!’

Within half an hour, Juana, stripped of her mud-plastered garments, washed, and enveloped in one of Mrs Craufurd’s dresses, which was quite three sizes too large for her, was seated before the fire in the salon, partaking of a comforting bowl of broth, and telling her story in her pretty, hesitant English to an audience composed of Mrs Craufurd and her two tall daughters. They could hardly believe that such a scrap of a girl could have gone through such a series of adventures; the Misses Craufurd plied her with questions, until their mother intervened, saying that it was not fair to plague their guest so.

No news came from the front that evening, and at about ten o’clock, Mrs Craufurd persuaded Juana to go to bed. She was so tired that although she had been sure she would not be able to sleep, she dropped off within ten minutes of her head’s being laid on the pillow.

7

While the family was seated at breakfast next morning, Mr Peters called to inform Juana that quantities of baggage were arriving in Antwerp, and that he would be very happy to look for hers if she would give him a description of it. An hour later, he came back, bringing West, and Matty, the spare horses, and all the baggage except Juana’s mattress, and the precious new dressing-case, which, in the sudden uproar, had been left behind at the village where the Brass Mare had bolted.

As the morning wore on, without any certain news being received from the front, Juana’s anxiety increased so much that she was unable to sit still, but walked about the room looking so distraught that Mrs Craufurd was half-inclined to persuade her to drink a few drops of laudanum to calm her nerves.

But in the afternoon, Colonel Craufurd came in with tidings that a great battle had been fought and won before the village of Waterloo. The French’ army was said to be utterly put to rout, and Napoleon himself flying towards Paris. There was no news of Harry, and after waiting all day for a message, Juana, to the dismay of her hostess, ordered West to have the Brass Mare brought round to the house at daybreak next morning. ‘But, my dear, you cannot venture alone!’ protested Mrs Craufurd. ‘At such an hour, too!” ‘I must rejoin my husband,’ Juana said resolutely. ‘I am accustomed to marching at dawn. Please do not try to dissuade me!’

‘I fear it would be impossible. Dearest child, how shall I say it? I don’t wish to frighten you, but have you considered-they say our casualties have been the heaviest ever known!’ ‘Yes, I have considered,’ Juana replied, quite calmly, but with a constricted throat. ‘If my husband has been killed, I must find his body.’

There was no moving her; she seemed all at once to be older than Mrs Craufurd had thought her; and nothing could have been more assured than the orders she gave for her servant’s following her with the baggage. She was plainly an experienced campaigner, and after trying for a little while to persuade her to await news of her husband in Antwerp, Mrs Craufurd gave it up, and busied herself instead with superintending the drying and cleaning of her soiled habit.

Taking an affectionate and grateful leave of her kind hosts, Juana rode out of Antwerp at three o’clock next morning, accompanied only by West. They reached the village by the canal in time for breakfast, and were fortunate enough to discover the lost dressing-case hidden away in the hayloft. By seven o’clock, they had reached Brussels, and almost the first sight encountered was that of a party of Riflemen, all of them wounded, and making their way through the streets to one of the tent-hospitals which had been hurriedly set up in the town. Juana spurred up to them, and was instantly recognized. They saluted her, but when she asked eagerly if they could tell her what had become of her husband, their replies were rather evasive, and they exchanged glances which at once aroused her suspicion. Finally; one of them said with a roughness which concealed his pity: ‘Missus, it ain’t no manner of use riding to the battlefield! There’s sights there not fit for a female. You go and bide quietly within doors!’

‘Loco! I was at Tarbes!’ she cried, striking her fist against the pummel of her saddle. ‘Tell me, instanteamente, is my husband alive? Is h e well?”

‘You’d best know the truth, missus,’ he said bluntly. ‘Brigade-Major Smith of ours was killed yesterday, quite early on in the day.’

She reeled in the saddle, growing so deathly pale that West put out a hand to catch her arm, fearing that she would faint. She did not, however. She looked at him in a blind fashion that quite unmanned him, and said: ‘We must hurry. We must make haste, for I must find his body.’

‘Missus, missus, don’t ask me to take you there!’ he begged. ‘Master wouldn’t have it so.’ ‘Master is dead,’ she said tonelessly. ‘I shall be dead, too, very soon, but I must see him once again before I kill myself. You need not come with me. I want no one now.’ He saw that it would be useless to try to stop her; he could only hope that on the battlefield she would meet some friend who would have more power to persuade her than he possessed.

They rode in silence, mostly at a gallop. The sights encountered on the chaussée leading through the Forest of Soignies were so terrible that West was not surprised to see Juana’s eyes dilated, with a look of horror bordering on madness in them. The endless procession of wounded soldiers, and horses, of carts with corpses in them, of dead men lying by the road, too shattered to have been able to crawl the weary miles to Brussels, was a nightmarish phantasmagoria comparable to nothing seen in all the years of the campaigning in the Peninsula. The village of Waterloo was full of wounded officers; farther on, at Mont St Jean, a horrible, creeping aroma of corruption set the horses jibbing and squealing, and made West break the long silence to beg his mistress to go no farther.

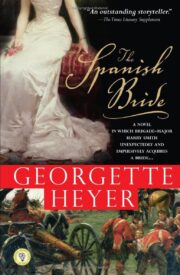

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.