Georgette Heyer

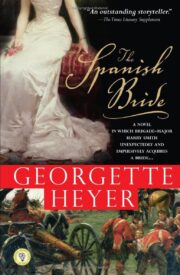

The Spanish Bride

The Spanish Bride

Georgette Heyer

1940

Author’s Note

Since a complete list of the authorities for a book dealing with the Peninsular War would make tedious reading, I have published no bibliography to The Spanish Bride, preferring to add a note for those of my readers who may wish to know which were my main works of reference.

Obviously, the most important authority for Harry’s and Juana Smith’s story is Harry Smith’s own Autobiography. Obviously again, it would have been impossible to have written a tale of the Peninsular War without studying Napier’s work, and Sir Charles Oman’s monumental History of the Peninsular War. I must acknowledge, as well, my indebtedness to Sir Charles Oman’s smaller work, Wellington’s Army; and I should like to thank both Sir Charles Oman, and Colonel Jourdain, for their kindness in searching for an obscure reference on my behalf.

I have not, to my knowledge, left any of the Diarists of the Light Division unread. Of them all, I found Kincaid and George Simmons the most useful for my particular purpose; but the details of the rank-and-file of the 95th Rifles were culled largely from Edward Costello’s Adventures of a Soldier. But Rifleman Harris was useful too; and so was Quartermaster Surtees, in spite of his unfortunate habit of covering all too many pages with moral reflections.

Outside the Light Division, Larpent’s Journals provided endless details. And there are grand bits to be found in Grattan’s Adventures with the Connaught Rangers; in Sir James McGrigor’s Autobiography; in Gleig’s Subaltern; in Gomm’s Recollections of a Staff-officer; and in Tomkinson’s Diary of a Cavalry Officer. There is a book of Peninsular Sketches, too, compiled by W. H. Maxwell; and all sorts of information to be gathered from the Lives of various commanders, not to mention the regimental histories. And last, but certainly not least, there are the Dispatches, and the Supplementary Dispatches, of Wellington himself.

— Georgette Heyer

Chapter One. Badajos

There was a place on the right bank of the Guadiana where hares ran strong. It was near a large rabbit-warren, quite a celebrated spot, which the officers of the army besieging Badajos had soon discovered. Sport had been out of the question during the first part of the siege when the torrential rain had fallen day after day, flooding the river, sweeping away the pontoon-bridges that formed part of the communication-lines from Badajos to headquarters at Elvas, turning all the ground round the town into a clay swamp through which the blaspheming troops struggled from their sodden camp to the trenches. Having broken ground on St Patrick’s Day, the army, which boasted a large proportion of Irishmen in its ranks, was confident that this third siege of Badajos would be successful. But the drenching rain, which persisted for a week, threatened to upset all Lord Wellington’s plans. From the moment of opening the first parallel, the most appalling weather had set in. Trenches became flooded; the mud in the gabions ran off in a yellow slime; and men worked in water that rose to their waists. It was harder to bear than the firing from the walls of the town, for it was disheartening work, and good infantrymen hated it. They called it grave-digging, labour for sappers, not for crack troops. There was, unfortunately, a dearth of sappers in the army. ‘Ah, may the divil fly away with old Hookey! Didn’t we take Rodrigo, and is ut not the time for others to ingage on a thrifle of work?’ demanded Rifleman O’Brien. On the 24th March the rain stopped, and fine weather set in. The digging of the parallels went on quickly, in spite of the difficulty of working in heavy, saturated clay, and in spite of the vicious fire from Badajos. The Portuguese gunners, bombarding the bastions of Santa Maria and La Trinidad, fell into the way of posting a man on the look-out to declare the nature of each missile that was fired from the walls. ‘Bomba!’ he would shout, or ‘Balla!’ and the gunners would duck till the shot had passed. Sometimes the look-out man would see a discharge from all arms, and, according to Johnny Kincaid, fling himself down, screaming ‘Jesus, todos, todos!’

With the better weather, thoughts turned to sport. A partridge or a hare made a welcome addition to any soup-kettle. It was Brigade-Major Harry Smith’s boast that there was not an officers’ mess in the and brigade of the Light division which he did not keep supplied with hares. In infantry regiments, in the general way, it was only possible for Staff-officers, with a couple of good remounts, to indulge in hunting or coursing, nor was it by any means every Staff-officer who owned a string of greyhounds. But Brigade-Major Smith was sporting-mad, and wherever he went a stud of horses and a string of Spanish greyhounds went too. If he had a few hours off duty, he would come into camp from the trenches, shout for a bite of food, swallow it standing, and set off on a fresh horse, and with any friend who could be induced to forgo a much-needed rest for the sake of joining him in an arduous chase. But however heavy the going the sport was good, hares being plentiful, and Harry’s greyhounds, despised by those who obstinately upheld the superior speed and intelligence of English hounds, generally successful.

The Brigade-Major was a wiry young man, rising twenty-five, with a dark, mobile countenance, a body hardened by seven years’ service in the 95th Rifles, a store of inexhaustible energy, and a degree of luck in escaping death that was almost uncanny. If he had not been such an efficient officer, he would have been damned as a harum-scarum youth, and had indeed often been sworn at for a madman by his friends, and his various Brigadiers.

His restless energy made his friends groan. ‘Oh, to hell with you, Harry, can’t you be still?’ complained Charlie Eeles, haled from his tent to the chase. ‘Oh, very well, I’ll come! Who goes with us?’ ‘Stewart. Bustle about, man! I must be back by six o’clock at latest.’ Grumbling, cursing, Lieutenant Eeles turned out, for although he had been on duty for six hours in the trenches, and was tired and cold, it was always much more amusing to go with Harry than to stay in camp. By the time he was in the saddle, Captain the Honourable James Stewart had joined them, mounted on a blood-mare and demanding to know what was keeping Harry.

The Light and 4th divisions being encamped on the southern side of Badajos, near the Albuera road, the three young men had not far to ride before crossing the Guadiana river. The weather, though dry, was dull, and the sky looked sullen. Badajos, crouching on rising ground in the middle of a grey plain, lay to their right, as they rode towards the river. A Castle, poised upon a hundred-foot rock, dominated the eastern side of the town, and overlooked the confluence of the Guadiana with the smaller Rivillas river. On this side of Badajos, Sir Thomas Picton’s Fighting 3rd division was encamped, and the parallels had been first cut. The French, defending the town, had built up the bridge that crossed the Rivillas near the San Roque gate, south of the Castle, and had strengthened the two weakest bastions of the town-those of San Pedro and La Trinidad-by damming the Rivillas into a broad pool, guarded by the San Roque lunette. This inundation stretched from the bastion of San Pedro to La Trinidad, its overflow seeping into cunettes dug immediately below the walls of the town. An attempt to blow up the dam had failed, on the and April, and the inundation remained, blocking the approach from the first and second parallels, and covering all the ground from the walls of Badajos to the Seville road. Beyond the inundation, an outwork, known as the Picurina fort, had been carried by a storming-party from the 3rd division, under Major-General Kempt, on the 26th March. West of La Picurina, and due south of the town, a strong out-fort, the Pardeleras, was still in French hands; and on the right bank of the river, north of the town, the San Cristobal fort, standing on a hill that overlooked the Castle, and the old Roman bridge that spanned the Guadiana, towered over all. In previous sieges, the attacks had been directed against San Cristobal, and had failed; but in this chill spring of 1812, Lord Wellington, fresh from the conquest of Ciudad Rodrigo, had marched his troops south through Portalegre and Elvas, on the Portuguese border, to invest Badajos on the south and east sides. Everyone knew that the assault was to be made on the weaker bastions of Santa Maria and La Trinidad, for these, and the curtain between them, were being relentlessly bombarded; and everyone knew that time was a more than usually important factor in these operations. Marmont, his headquarters at Valladolid, might be contained by a covering force of Spaniards to the north; but there was news that Soult, with the French army of the South, had broken up from before Cadiz, and was moving to the relief of Badajos.

The bad weather had delayed the siege-work; there had been the usual trouble over transports; and a hundred and one checks and annoyances. The Engineers’ Park was stocked with cutting-tools sent up from Lisbon, but the senior Engineer, Colonel Fletcher, had had the misfortune to be wounded in the groin during the early days of the investment, and was compelled to direct the operations of his subordinates from a bed in his tent. Admiral Berkeley, in command of the squadron at Lisbon, sent, instead of the British guns he had been requested to lend to the army, twenty Russian guns which were of different calibre from the British 18-pounder, and would not take its shot; while a Portuguese artillery officer, anxious to be helpful, added to Colonel Dickson’s worries by unearthing from a store in Elvas some iron and brass guns of startling antiquity.

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.