They said in London that it was the hardest winter within the memory of man. Never had there been such a frost! Sand had to be scattered in the streets to prevent the horses sliding on the glass-like cobble-stones; ladies pulled snow-boots on over their kid shoes, dug their hands deep into fat little muffs, and, in defiance of fashion, wore fur-lined coats over their foolish muslin dresses. Actually, the Thames was frozen, and fairs were being held on it. Charlie Beckwith, and Jack Molloy, on leave from Dover, where the regiment was quartered for the winter, took Juana and Anna to see the fun there one evening. A capital time they had, but it was not at all the kind of entertainment of which Mary would have approved. They bought roast potatoes, and held them in their muffs, to warm their hands; they paid their groats to see the Fat Woman, and the Calf with Five Legs; they even tried their luck at the cock-shies, just like all the vulgar cits, declared Anna joyously.

Beckwith and Molloy had plenty of regimental gossip for Juana, and oddments of news about the troops stationed in Holland. Beckwith said he had it on the best of authority that ever since his father’s restoration to the throne, the young Prince of Orange, who had been made Commander of the British forces in the Netherlands, had been giving great offence to the Dutch by associating almost exclusively with the English in Brussels. Colborne, a full Colonel now, and a KCB besides, was his Military Secretary: no sinecure, thought Beckwith.

Jack, drawing the grimmest picture of the bleak barracks at Dover, wished that the 95th had been ordered to the Netherlands. Brussels seemed, by all accounts, to have become the gayest city in Europe. The English, delighted at being at last able to travel out of their own island, were flocking to Belgium in hundreds. Jack knew a fellow who had the luck to be stationed there; he said that London was nothing to it. ‘Better even than Madrid!’ Jack said, teasing Juana.

When they went home to Whittlesey, no sooner had the chaise drawn up in St Mary’s Street, than Sam ran hallooing out of the house to tell Juana to come inside quick, and see what a surprise was awaiting her. A surprise could mean only one thing; she picked up her skirts and ran in; and there, sure enough, was Eleanor, clutching a shawl round her shoulders, and holding out a letter from Harry.

Such a long letter it was, written like a journal on board the Statira, and sent off from the mouth of the Mississippi, on the 25th December. Only fancy! The Statira had taken all that time to reach her rendezvous with the fleet. But Harry said that was on account of her captain’s being one of the old school, and making all snug each night by shortening sail. It did not seem, though, as if Harry had chafed much at the delay. He had enjoyed the voyage, in spite of the frigate’s being so crowded that most of the Army officers had had to sleep in cots in the steerage. There were many Peninsular comrades on board, and Sir Edward Pakenham, ‘one of the most amusing persons imaginable’, inspired Harry every day with increasing respect and affection. ‘I never served under a man whose good opinion I was so desirous of having,’ he wrote.

He had found time to scrawl a few lines after landing in America. Owing to the Statira’s leisurely voyage, he said, they had arrived three days after the disembarkation of the Army, under Major-General Keane. The force had sustained a sharp night-attack; Stovin, the Adjutant-General, had been wounded in the neck; and Harry was promoted to his room. This was naturally very good news; but the announcement that the army was assembling for an assault upon New Orleans quite superseded it. The reflection that the engagement must by this time be over, for good or ill, chased away the smiles from the sisters’ faces, and made Juana clutch Harry’s letter to her breast, exclaiming: ‘He may be dead! He may be dead! Ah Dios, how can I bear to wait and wait for the news?’

A most painful period of anxiety had indeed to be lived through before any further tidings came from America. The snow that covered the fens had turned to slush, when, upon a dull February day, Brother William brought in the Gazette. He was looking so grave that Eleanor, who met him at the door, uttered a muffled shriek, and said hoarsely. ‘Harry?’ ‘No, thank God! He is safe! But the news is shocking! We have suffered a terrible reverse.’ ‘Oh, what does that matter as long as dear Harry is safe and well? Quick, come in at once to Juana!’ She paused. ‘But how do you know?’ she asked. ‘Is there a letter from him?’ ‘No, something better than that: General Lambert mentions him in the Dispatch!’ She could not forbear to seize the Gazette from him, and to direct her gaze towards the few lines his finger pointed out to her. ‘Major Smith of the 95th Regiment, now acting as Military Secretary, is so well known for his zeal and talents, that I can with great truth say that I think he possesses every qualification to render him hereafter one of the brightest ornaments of his profession,’ she read and at once cried out: ‘Oh, what joy! How Juana will feel this! Our Harry! Military Secretary! His zeal and talents! Oh, I must find Juana directly!’ This was soon done, and it was not until she had exclaimed over the tribute to Harry, flying up out of her chair, and dancing about the room like the child she was, that William could get anyone to attend to the rest of the Dispatch. But as soon as Juana heard that the Dispatch had been written by Major-General Lambert, her jubilations were checked in an instant, and she said sharply: ‘Lambert? You mean Pakenham, our dear Sir Edward!’

‘No; alas, Pakenham was killed. Our arms have met with a reverse, my dear sister.’ ‘Killed!’ Juana cried, turning pale. ‘Reverse! It is not possible! Give me the Gazette immediately! I do not believe you!’

But it was quite true. The assault upon New Orleans had been repulsed with shocking loss, and Pakenham’s body, enclosed in a cask of spirits, had been actually brought home to England for burial.

Juana burst into tears. Not even Harry’s safety and promotion could alleviate her distress at hearing of a British defeat. She said over and over again that it could not be: ‘Never, never did we lose a battle! Oh, why was not Lord Wellington in command? It could not then have happened!’

Upon the following day, a packet arrived from Harry, enclosed in a very civil note from Wylly, Pakenham’s Military Secretary, who had brought home the dispatch.

Harry’s letter was written again in the form of a journal, but it was a hurried, disjointed scrawl, showing plainly how busy and how harassed he had been ever since his landing in America. He had been dissatisfied with several of the regiments from the start; he discovered early that the American Riflemen, though slow, were excellent shots; and it was plain that he considered the enemy to have been very strongly placed. Only on one subject did he write with his usual enthusiasm. ‘I am always with Sir Edward …. I am delighted with Sir Edward; he evinces an animation, a knowledge of ground, of his own resources and the strength of the enemy’s position, which reminds us of his brother-in-law, our Duke. .. I do believe I am more attached to Sir Edward, as a soldier, than I was to John Colborne, if possible!’ The last lines of Harry’s letter were more disjointed than ever, evidently written in great agitation. Before the assault, on the 8th January, Harry had had to give up his post of Adjutant-General to a senior officer arrived to fill Stovin’s place. Lambert’s brigade having landed, he had been sent to it as AAG. He expected Juana would remember Lambert at Toulouse: a gentlemanlike, amiable fellow, very much a Guardsman. Harry had known, twenty-five minutes before the fall of Pakenham, what the end must be. ‘I said, in twenty-five minutes, General, you will command the army. Sir Edward will be wounded and incapable or killed. The troops do not get on a step. He will be at the head of the first brigade he comes to.’

That was what had happened. Pakenham had fallen, the attack had failed. Never since Buenos Ayres, wrote Harry, had he witnessed a reverse: that was what made it doubly hard to bear. He was so busy that Juana must forgive him for writing only a short letter. In spite of his detestable scrawl, Lambert had made him Military Secretary; he had been sent with a flag of truce to General Jackson; he would be going again, to propose an exchange of prisoners. Wretched work, but thank God he had found a most liberal, clear-minded man to deal with in Jackson’s Military Secretary, Lushington! He could give Juana no more news, except that the army would shortly re-embark. She would read the rest in Lambert’s dispatch.

2

Hardly had England had time to recover from the news of the reverse in America than she was stunned by a far more shocking event. On 26th February, Napoleon Bonaparte escaped from the island of Elba.

Consternation reigned in London; it spread swiftly over the country, and nothing was anywhere talked of but the Ogre’s landing in the south of France. Pessimists prophesied that with half the army in America, and Wellington far away with the Congress in Vienna, there would be no stopping Napoleon. He would overrun France, and Europe too, very likely; there would be no more peace for anyone.

John Smith looked grave, and shook his head, but Juana said: ‘Oh, basta! The Duke will come back from the Congress; yes, and Enrique will come back from America, because you know it is certain now that the peace will be signed; and again we shall be on the march, with all our friends! Oh, I am happy, I am happy, I am happy!’

‘How can you talk so?’ Mary exclaimed.

‘My little tent-the columns marching-West leading Enrique’s spare horse-the camp fires-Oh, you do not know, you cannot understand how much I want it all again!’ ‘Well!’ Mary said. ‘To wish to plunge Europe into war again, for any consideration in the world, is something I hope I may never understand !’

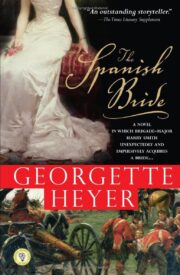

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.