That was all very well, and certainly relieved his lordship’s mind of one of its cares. But the war-chest was still in a bad way, and promissory notes were hard to meet, while the long-suffering infantry was six months in arrears of pay. ‘I can scarcely stir out of my house on account of the public creditors waiting to demand what is due to them,’ wrote his lordship, never one to understate a grievance.

It was annoying, but neither the Basques nor the French could be induced to accept Spanish or Portuguese silver, which was all the loose cash the war-chest held. His lordship published notices informing the mistrustful people how much the dollar and the real were worth, but they continued obstinately to refuse dollars. So his lordship wrote a private letter to Colonels commanding battalions in the army, promising, in the coolest way, indemnity and good pay to all professional coiners in the ranks who would step forward. He got about fifty of these gentlemen, spirited them away to St Jean de Luz, set up a secret mint there, and put them to work on the Spanish silver in the war-chest. The dollars disappeared, and excellent Napoleonic five-franc pieces began, mysteriously, to circulate in their place. The weather, throughout December and January, continued to be shocking, and made troop movements impossible. The army remained in cantonments, fretting a little at inaction. But his lordship, for once in his life, was not altogether displeased at the inclemency of the season. He did not wish to advance much farther into France until he should be informed of the Allies’ intentions. Did they contemplate making peace with Napoleon? Did they mean to support the Royalist claims? Or were they considering the possibility of setting up a new republic? His lordship could not discover that there was much enthusiasm for the Royalist cause, but was inclined to think that if he were a Bourbon prince he would come to France, and take his chance. He said that the people of southern France, though heartily sick of the Bonapartist regime, did not seem to care much what form of government was to succeed it. So the Duc d’Angouleme came incognito on a visit to headquarters. He was rather an odd person, and his lordship’s personal Staff, who dubbed all distinguished visitors to headquarters Tigers, promptly christened him the Royal Tiger. He found the Field-Marshal’s headquarters quite devoid of any pomp or ceremony, no one, from the youngest ADC to the Field-Marshal himself, putting on any of the airs of a great man. It was rather disconcerting at first to find Lord Wellington’s family composed of very young gentlemen with a flow of inexhaustible high spirits, and a nice taste in fancy-waistcoats; and most bewildering to hear his lordship and all the big-wigs in the army joking and laughing with these sprigs from the Universities, just as though they were all members of one big, jolly, family, but the Duc soon grew accustomed to it, and settled down quite happily.

2

In January, upon its becoming known that General Skerrett was not going to return to his brigade, Colonel Colborne’s temporary command came to an end. He went back to his regiment, but the blow was a good deal softened by the appointment of Colonel Andrew Barnard in Skerrett’s room.

Colonel Barnard, who had commanded the entire division during the siege of Badajos, was a splendid soldier, and the most cheerful, hospitable fellow in the world, said his officers, affectionately welcoming him back. The wound in his chest was not by any means healed, but he said that he was in the best of health, and owed his life to the devoted attention of George Simmons. No one but George had been allowed to doctor him, and as soon as he could stand on his feet he had taken George with him to St Jean de Luz, where he had stayed for some time. George had actually dined at Lord Wellington’s table, so that it was a wonder, said his messmates, that he deigned to consort with his humbler friends any more. George received all the chaff with his placid grin, but said seriously that to gain the friendship of a man of Colonel Barnard’s ability would always be of use. Colonel Barnard had presented him with a handsome gold watch, especially sent from London, which George showed proudly to everyone; and in the New Year George was appointed to superintend the new Light division telegraph, at the Chateau d’Urdanches. ‘George, you’re becoming a great man!” his friends told him.

‘No, no!’ protested George. ‘Only I am determined to make my way in the army, and I cannot but be grateful for the chance which led to my being singled out.’

Brother Maud, returning from St Jean de Luz, whither his battalion had been sent to get new equipment, visited George in his log-house by the telegraph-post. He ate a tight little beefsteak with him, and went off with George’s good mule in exchange for his own broken-down pack horse. George’s friends thought that Maud’s visits closely resembled the descent of locusts upon the plain, but George was always glad to see his graceless brother, and could be relied upon to find any number of excuses for his predatory habits. With the appointment of Barnard to the command of the and brigade, the 1st Rifle battalion, of which he was Colonel, changed places with the and, an alteration which could not be other than agreeable to Harry, who belonged to the 1st battalion, and was delighted to have his particular friends in his own brigade.

In February, the weather unproved, and his lordship began to complete his arrangements for driving Soult out of Bayonne. His manoeuvres were very bewildering to Soult, a much harassed man. His Emperor had demanded three divisions from him, and Soult obediently sent them off. This left him in the uncomfortable position of being numerically inferior to Lord Wellington. He had been drilling conscripts throughout January, but even conscripts were hard to come by, since the young Gascons fled to the woods to escape being forced into the army. The Emperor’s advice to him was not at all helpful, and consisted largely of instructions to him to make the best of his situation.

It seemed to Soult that his adversary’s thrust must come somewhere between Bayonne and Port de Lanne, some thirty or more miles farther up the Adour; and he began to move troops eastward, with the intention of striking at Wellington’s flank when the attempt to cross the river should be made. That Wellington meant to cross below Bayonne, right at the river’s mouth, never occurred to him. When Wellington began to move eastward, with the greater part of his army, leaving only Hope with 18,000 English and Portuguese troops round Bayonne, the Marshal thought his reading of the situation correct, and obligingly drew off yet more of his troops from Bayonne.

Wellington had been forced to call up Freire’s and Carlos de Espana’s Spaniards to reinforce Hope. He had to feed them, of course, which he could ill-afford to do, but even that drain upon his magazines was preferable to letting them subsist on the country. On the 12th February, his lordship began his movement, with the object of pushing the enemy back from river to river until he should have manoeuvred him too far eastward to permit of his returning to the Adour.

It was not, however, until four days later that the Light division, forming, with the 6th, the rear of Beresford’s force, broke up from cantonments. They marched without the 1st Rifle battalion and the 43rd regiment, which had both gone off to St Jean de Luz to get new equipment, and they were extremely disgusted at not being in the van of the army. ‘A Rifleman in the rear is like a fish out of water,’ said Kincaid once.

Hill’s flanking force, on the left of the Allied line, had the honour of beginning the movement; and it was not until the French General Harispe, retreating first to Le Palais on the line of the Bidouze, and then to the line of the Saison, at last was driven to a position behind the Gave d’Oloron, that Beresford received orders to march. The and division, and old Picton’s 3rd, advancing north of Hill, were having all the sport, said Beresford’s men. But everything was working out just as his lordship had meant it to. The whole of Clausel’s force had been obliged to fall back behind the Gave d’Oloron, from Peyrehorade to Narreux, a front of thirty miles; and on the 18th February, it was learned that two out of the three divisions left to guard Bayonne had been ordered to march east.

Beresford was told to push on. He marched with Vivian’s and Lord Edward Somerset’s cavalry brigades flung out in front of his infantry. The Enthusiastics, and the 7th (whom men of the older divisions unkindly called the Mongrels), followed the cavalry; the Light division came next; and the 6th, bringing up the extreme rear, had not as yet overtaken the force. The Light division, ordered to halt for a day at La Bastide Clarence, on the Joueuse, heard of Hill’s fights at Garris, and Arriverayte, and growled. Hill was rolling up the French in famous style; Picton was pressing forward; and the Division, the very spearhead of attack, was kept kicking its heels twenty and more miles in the rear.

The weather was stormy, and very cold. Lord Wellington snatching a day to visit Sir John Hope, found big seas breaking on the coast-line, and Admiral Penrose unable to bring his chassemarées, which were to form a bridge across the Adour, into the mouth of the river. That was vexatious, but his lordship remained calm, unlike Marshal Soult, who was talking rather wildly of being opposed by an army of a hundred thousand men. The Marshal, very much puzzled by his lordship’s manoeuvres, had already made up his mind to abandon the line of the Gave d’Oloron, and to fall back behind the Gave de Pau, with the strong position of Orthez in his rear.

On the 21st of the month, Wellington was with Hill, at Garris; on the following day, the Light and 6th divisions were directed to fall in with Hill’s force.

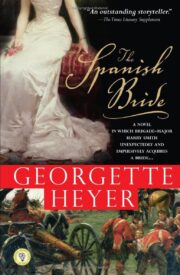

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.