She was deathly pale, her chest labouring. She tried to smile, to speak, but the shock had been too much for her, and to West’s dismay she fell at his feet in a deep faint. She did not come round until he had carried her back into the cottage, and laid her on her bed. He was in a great state of anxiety about her, and between splashing water over her, and shouting to Jenny Bates to get some feathers to burn under her nose, seemed in danger of becoming quite distracted. But in a few moments, Juana recovered consciousness, and tried to sit up.

Jenny Bates, elbowing West out of the way, pushed her back on to her pillow. ‘Now, you lie still, missus, do! That’s enough of watching nasty battles! If some people had the sense they was born with, they never would have let you go agaping out of the window!’ ‘Not Old Chap!’ Juana said in a husky voice. ‘I saw. It was poor Algeo! Oh, West, look out and tell me what is happening!’

‘He’ll tell you our men are safe on top of the hill, and no need for any of us to worry our heads over them!’ said Jenny, in such minatory accents that West took the hint, and reported the brigade to be in possession of the heights.

‘Oh, is it true?’ Juana said. ‘Are you sure?’

‘Why, where else would they be?’ demanded Jenny scornfully. ‘You don’t want to fret about master, for he’s enjoying himself, same as my man will be, if I know them! Men! Yes, there’s nothing they like better than to go mixing themselves up in a nasty, bloody battle, fair frightening the wits out of decent women, and themselves like a set of pesky lads out of school! You lie quiet now, and see if master don’t come bounding in presently, as right as a ram’s horn, and telling you what a rare day’s fighting he’s had!’

‘If you are sure it is all over!’ Juana said, with a shudder. ‘But I can still hear firing!’ ‘Ay, but it’s not our men,’ West assured her. ‘Of course it’s all over! I daresay master will be standing there, atop of the hill with the Colonel, at this very moment.’

3

But the brigade, in spite of having possessed themselves of the first redoubt, had still some way to go before they reached the defences on the ridge of the Bayonette, and Harry, so far from standing there with his Colonel, was riding back as hard as he could to Cole’s supporting division.

The Enthusiastics had pushed forward up the slope of the bill, and as soon as Cole heard that Colborne meant to press on, he said in his quick way: ‘Rely on my support! By God, you’ll need it, for you have a tough struggle before you! Magnificently done, sir! magnificently done, indeed! Everyone is talking of your charge!’

Harry turned, and spurred Old Chap up the hill again. As soon as he was assured of Cole’s support, Colborne threw out a screen of Riflemen in skirmishing order, and advanced the whole brigade under a murderous fire from the ridge. Many of the shots, however, went over the heads of the men, while the Riflemen, firing uphill, found their marks with awful precision. The French continued firing from behind the parapets until the British, advancing steadily all the time, were almost upon ,them. A very short hand-to-hand fight followed, but instead of defending their rather formidable position with the determination the British had expected them to show, the French suddenly abandoned it, rushing away down the steep side of the ravine in their rear.

Colborne, Harry, Winterbottom, the Adjutant of the 52nd, and Tom Smith were in the forefront of the fight, and upon the Frenchmen’s flight into the ravine, they all four of them pushed on in pursuit, with some ten of the swiftest-footed men in the brigade racing after them. On the opposite side of the ravine, they saw a small detachment of the Riflemen from Kempt’s brigade, who had reached the crest of the opposite spur, and were pushing forward.

‘Where are you going to, Colonel?’ shouted Harry, his eyes blazing with excitement. ‘Why, to reconnoitre a little, to be sure!’ replied Colborne.

The ravine expanded rather unexpectedly, and a column of quite four hundred Frenchmen was suddenly exposed.

Harry began to laugh. Tor God’s sake, Colonel, take care what you are about! You have clean outstripped our own column! What shall we do?’

‘Oh, there’s nothing for it but to put a good face on the matter!’ said Colborne. ‘I daresay they will think Kempt’s fellows on the other ridge the head of a column. Come on!’ He clapped his spurs into his horse’s flanks, and galloped up to the officer at the head of the enemy column. ‘You are cut off,’ he said in French, and for all the world (thought Harry) as though he were supported by ten thousand men. ‘Lay down your arms!’ The officer, though taken by surprise, remained perfectly cool. He glanced up at the Riflemen on the ridge, and for a moment Harry thought that he had guessed that the ten men in sight comprised the whole force. But apparently he supposed them to be the head of a large column, for he turned back to Colborne, and, presenting the hilt of his sword, said: ‘I surrender to you a sword which has ever done its duty, monsieur!’

Colborne received it, bowing gravely. The three officers behind him, taken as much by surprise as the Frenchman, wondered what he would do next, but with his usual presence of mind, he said: ‘Face your men to the left, and move out of the ravine.’ His tone was so calm, his bearing so assured that Harry was not at all surprised that the order was immediately obeyed. He was extremely glad to see the Frenchmen separated from their weapons, but while he stood, trying to suppress the laughter that was consuming him, Colborne turned, and said: ‘Quick, Smith, what are you doing there? Get a few men together, or we are yet in a scrape!’

Harry, recalled to his duty, said hastily: ‘Yes, sir!’ and rode off to hasten the march of the men behind Colborne. He found them on the ridge, forming up, and soon brought them down to where Colborne was exchanging civilities with the French officer. Young Cargill, a very Scotch subaltern of the 52nd, marched the prisoners off to the rear under escort, while the rest of the column pushed on into French territory.

By this time it was growing dark, and Harry was sent to halt the brigade, just as one of Lowry Cole’s ADCs came riding up to ask Colborne, with General Cole’s compliments, how much farther he intended to go. ‘For Sir Lowry says, sir, that he don’t intend to go any farther!’ ‘Oh, I have gone quite far enough!’ replied Colborne.

The brigade bivouacked on the ground it had won, the men lying by their arms, and a fine drizzle of rain falling all night. No baggage having come up, conditions were miserable, but everyone seemed to be in excellent spirits. Fires were laboriously kindled, rum washed down the ration of biscuit, and Colborne had the satisfaction of overhearing a private of his own regiment sing out: “The Colonel’s health! and damn the man who gets a shot into him!’ Morning brought young Cargill back to the brigade. Having marched his prisoners to the rear, he had spent the night snugly in Vera, a piece of intelligence which made his fellow-officers, rubbing cramped limbs, swear at him. He went off to make his report to Colborne, whom he found toasting sausages with his Staff.

‘Well, you look very spruce, Mr Cargill,’ said Colborne, himself unshaven and dirty. ‘Get those prisoners safely to the rear?’

‘Yes, sir. And I met Lord Wellington on the way, sir, just about dusk, it would be.’ ‘You did, did you?’

‘Yes, sir. His lordship called out to me, “Hallo, sir, where did you get those fellows?” and I told him, “In France: Colonel Colborne’s brigade took them!”

‘Oh, that’s why you’re looking so confoundedly pleased with yourself, is it?’ said Harry. ‘Well, it was his lordship himself,’ replied Cargill, with simple pride. ‘And he said to me, “How the devil do you know it was France?” Och, I knew that! “Because I saw a lot of our fellows coming into the column with pigs and poultry, which we had not got on the Spanish side,” I told him.’

Colborne started up, a very black look on his face. ‘Why, Mr Cargill, you were not such a blockhead as to tell his lordship that, were you?’

‘What for would I not? It was true as death!’ said Cargill, round-eyed.

‘You young fool, don’t you know better than to talk about the men’s plundering to Wellington? Get back to your regiment, sir, get back to your regiment!”

Cargill withdrew, very crestfallen. Harry was laughing, but Colborne said: ‘I shall hear more of this.’

However, when he rode off to headquarters a little later, he found his lordship in a very good humour.

‘By God, Colborne, your fellows did damned well!’ said his lordship energetically. ‘But you know, though your brigade have distinguished themselves even more than usual, we must respect the property of the country.’

‘I’m fully aware of it, my lord. I can rely on the discipline of my soldiers, but your lordship well knows that in the very heat of action a little irregularity will occur.’

‘Ah, ah!’ said his lordship. ‘Stop it in future, Colborne!’

Such a mild reproof, accompanied as it was by a smile and a nod, quite staggered Colborne. He told Lord Fitzroy Somerset, whom he applied to on Harry’s behalf, that he had never known his lordship to be in such excellent temper.

‘Oh, he was watching your little affair yesterday!’ replied Fitzroy. ‘There was nothing ever like it, Colonel! I wish you might have heard his lordship: he said the charge of the 52nd was the finest thing he ever saw. You’ll be mentioned in the dispatch.’

‘Well, I don’t care about that, but I want a brevet-majority for Smith.’ ‘I don’t think there will be any difficulty about that,’ said Fitzroy. ‘I’ll see to it.’ So back went Colborne to the brigade, and, finding Harry presently, said: ‘Well, give me your hand, Major Smith!’

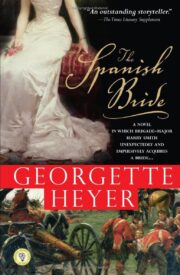

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.