‘Colonel Colborne, you insubordinate varmint!” said Harry. ‘Coronel Colborne,’ said Juana obediently.

‘If I were you, I would not pay too much attention to Smith,’ interposed Colborne. ‘I don’

t think I like Coronel Colborne, and you will never get your tongue round Colonel.’ The news of the breaking of the Armistice of Plasswitz reached Wellington on the 3rd September, with rumours of the battle at Dresden, but the siege of the fortress of San Sebastian dragged on for another week. A corps of Sappers and Miners had arrived in the Pyrenees, but they had come too late to be of much assistance. A bad business, San Sebastian: just like every other siege his lordship had engaged on. As for the taking of the town, best draw a veil over that, said those who had seen something of the sack. The fortress surrendered at last on the 8th September, and the army began to talk hopefully of an advance. It was already obvious that there were to be no regular winter-quarters this year, and everyone except Lord Wellington was itching to set foot on French territory. His lordship was not quite so anxious to lead his mixed force into the enemy’s country. It was one thing for them to plunder in Spain; quite another for them to do so amongst a hostile population. Already the Judge Advocate had a case to try of a soldier who, arrested for rape at Urdug, pleaded in extenuation of his crime that he had thought himself in France, and that there it was all regular. This kind of thing did not augur well for the army’s future behaviour; but far more harassing than the British soldiers’ probable misdemeanours was the prospect of the Spaniards revenging themselves upon the French as soon as they crossed the frontier. There was little doubt that they would conduct themselves damnably, thought his lordship; more especially since their supply columns were so badly organized that the greater part of their forces were half-starved, and ragged.

His lordship was receiving information out of France which he mistrusted. He was assured that Napoleon had become very unpopular in the south; that there was a strong Royalist party there; that the country people would welcome the advance of the British. ‘H’m! I daresay,’ said his lordship, unimpressed.

But by the middle of the month, a full report of the battle at Külm had reached him, and he began at last to prepare for the advance.

The French, meanwhile, were working like swarms of ants to render their positions more secure. Colborne and Harry used to ride out to watch them building their redoubts and entrenchments. There were two heights in front of Vera, called La Grande Rhune, and La Petite Rhune, which were separated one from the other by a narrow gorge through which the Nivelle flowed. La Grande Rhune, its steep slopes studded with gorse bushes and rocky outcrops, made the Scots remember their Highlands. Secondary heights, like tongues of land, formed a part of the great mass; two of them, called the Bayonette and the Commissari, loomed above Vera, and were extensively protected by entrenchments and forts.

The advance across the Bidassoa was held up for longer than had been expected by the state of the fords on the lower river, which, until October, were still too deep to allow Graham’s force, now commanded by Sir John Hope, to pass; but on the 6th October, the impatiently awaited orders were brought to the Light division by Colonel Barnard, from headquarters. There was much dancing and singing that night, for the division, having come to regard itself as a superb fighting unit, was never quite happy unless on the move. That the task allotted to Colborne’s brigade looked, to say the least of it, to be extremely unpromising, worried no one. Colborne himself had reconnoitred the French position, and the brigade had no doubt that under his leadership they would do all that was expected of them. The Rifles were happy, because theirs was to be the honour of opening the attack; and the men of the 52nd were happy because under cover of the skirmishing screen of Rifles they were going to storm the redoubt on one of the three hill-tongues above Vera. The attack by the Light division, with Lowry Cole’s 4th division in reserve, was to be made in two columns. Kempt’s brigade, striking to the east, after driving in the outposts in the Pass of Vera, was going to outflank the Rhune behind it; while Colborne, attacking the trenches above the town on the Bayonette and the Commissari heights, would turn the hill from the south-west. Since the Bayonette was a steep, narrow spur, blocked by three successive forts, it was plain that Colborne’s brigade had been given the harder task to accomplish. Colborne would not allow the pickets to be changed at daybreak, but ordered them to move on, so that the whole brigade was in Vera town before the French were aware of the impending attack.

The advance began a little after seven in the morning, Colville’s division distracting the enemy by noisy demonstrations at Urdax, away to the east; but the Light division, which was the most forward unit of all, did not come into action until the head of Cole’s column appeared, at about two in the afternoon.

‘Now, Smith, you see the heights above us?’ said Colborne. ‘Yes, and I wish we were there!’ replied Harry.

Colborne laughed. ‘Well, when we are, and if you are not knocked over, you shall be a Brevet-Major, if my recommendation has anything to do with it.”

2

From the window of the cottage which had for so long been the Smiths’ quarters, Juana was able to watch the whole attack. The cottage was hardly out of musket-range, but nothing would induce her to retire from it. She said she wanted to see a battle, and if Harry sent her to the rear she would return the instant his back was turned. She was excited, and nervous, not for herself but for Harry, and West could not prevail upon her to move away from the window. She kept thinking that she could pick Harry out amongst the mounted officers, and although it was impossible that she could recognize him at such a distance, this conviction very soon put her into a fever of anxiety. The Rifles, dark-habited troops in advance of the red-coats, seemed to be swarming all over the slope of the Bayonette. Spurts of fire from behind bushes and crags of rock showed that they were availing themselves of every bit of natural cover, but the Bayonette looked to be so precipitous that it did not seem possible for any troops to scale it.

‘It’s safer shooting uphill than down,’ said West comfortably. ‘Nor master isn’t with the skirmishers. It’s not likely he would be, in his position.’

‘Oh, he is always in the most dangerous place!’ said Juana, wringing her hands. ‘I wish I had not stayed! This is terrible!’

‘Well, now, missus, do but let me saddle Tiny, and I’ll take you away!’

‘No, no, not for anything in the world! How could I possibly go away?’ she replied, not stirring from the window. ‘I am glad he is riding Old Chap. It is better to be mounted on a good horse, isn’t it, West?”

West assured her that it was half the battle, but she hardly attended to him, crying out suddenly that the Rifles were being thrown back. This brought him to the window, and he saw that what she said was true, the French having rushed out in great numbers from the redoubt on the spur of the hill, and driven the skirmishing line back. They had, in fact, mistaken the Riflemen, in their green uniforms, for a detachment of Caçadores, and were considerably discomposed when they discovered their mistake. For the 52nd had come up behind the Rifles, and as these fell back, Colborne led his regiment forward in a grand charge which carried the first of the redoubts.

From the cottage window, it was hard to see anything but confusion on the hillside. There was a great deal of noise, and the struggle, swaying uphill and down, looked to be such a desperate business that Juana involuntarily covered her eyes. Upon West’s pointing out to her a little knot of persons visible on a hill-crest overlooking the whole, and telling her he could clearly detect Lord Wellington in their midst, she looked up again, childishly hoping that his lordship would send instant help to Harry’s brigade.

She would have been indignant had she known that at that very moment an ADC had galloped up to General Alten with a message from Kempt, a mile away, and out of sight round the flank of the Grande Rhune, to ask if the 52nd regiment could give him some assistance.

‘Colonel Colborne gif him some assistance!’ said Alten. ‘If he could see der hill Colborne’s Prigade is on, he’d see dat Colborne has quite enough to do himself!’ The dropping of men upon the slope of the Bayonette was a sight too heartrending for Juana to bear. She turned away with a shudder, begging West, however, to keep a sharp look-out. He was able, presently, to tell her that the 52nd had reached the first redoubt, and that the Rifles and the Caçadores were fair murdering them Frenchies on their retreat to the top of the ridge.

She ran back to the window, but had scarcely reached it when a chestnut hunter came galloping to the rear, his saddle empty, and his rider, caught by one foot in the stirrup, dragged over the ground beside him.

A shriek of the wildest despair burst from Juana. ‘Old Chap!’ ‘My God it is!’ West muttered.

Juana ran out of the cottage, her desperate fear lending her such speed that West, though he ran as fast as he could, was not able to catch up with her. The dead man, his foot freed from the stirrup, was lying in a heap some distance away, but the chestnut still came on, bolting in terror away from the battle-ground. Colour and marking were the same as Old Chap’s, but as he galloped past her Juana recognized him, and stopped running. West, pounding up behind her, gasped out: ‘Missus, it’s not Old Chap! It’s that Portuguese Colonel’s horse that’s the living spit of master’s!’

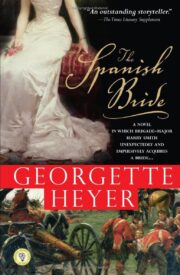

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.