That was too good a story to be withheld from the brigade. Skerrett’s table became a standing joke, which spread through the division. As for seven sheep, and ten bottles of claret, Harry and Fane found them quite insufficient for the scale of their own hospitality. The joke had barely had time to grow stale, when Skerrett announced his intention of giving a grand dinner. His ADC and his Brigade-Major, when this news was broken to them, carefully avoided meeting each other’s eyes. ‘Whom do you invite, sir?’ Harry asked. ‘I must ask Barnard and Colborne, of course, and Blakeney, and some others. You and Fane will naturally be present, and I shall look to you to take care of everything,’ said Skerrett.

They assured him that they would do so, but when Harry asked whether he should lay in provisions for the banquet, Skerrett said No, he preferred to attend to that himself. ‘One can’t expect to fare very well in bivouac,’ he said, ‘but I daresay my cook can contrive a respectable dinner.’

Since he had the worst cook in the division, neither Harry nor Fane shared his optimism. Where were the supplies coming from? Where was the wine to be had? ‘Barnard, of all people!’ Harry chuckled. ‘He’s had a French cook ever since Salamanca, and oh, how he loves his dinner and a good bottle of wine! “Can’t expect to fare well in bivouac!” Why, doesn’t the old fool know that Colborne and Barnard are famous for their dinners? I’ll tell you what, Tom: we shall sit down to steak and black strap!’ ‘He must mean to provide something better than black strap!’ Tom said. He was right. When Harry called upon his Brigadier for orders, on the morning of the feast, he found him dressed for travel. ‘Where are you going, General?’ he asked. Skerrett, at first shocked by the free-and-easy ways of Light division officers, had become resigned to his Brigade-Major’s lack of ceremony, and replied that he was off to Lesaca. This could only mean that he was going in search of supplies, so Harry promptly told Fane that they had misjudged the fellow, and he was actually going to buy suitable provisions from the sutler at headquarters.

Fane’s rather simian countenance wrinkled in an effort of deductive reasoning, ‘Headquarters’ prices won’t do for Skerrett,’ he said. ‘I believe you’re wrong. It’ll be steak and fowls-tough.’

“Then why has he gone to Lesaca?’ ‘I don’t know,’ said Fane, ‘but I’ll find out’

He posted himself, accordingly, as a look-out, and arrived at the cottage he shared with the Smiths only just in time to get ready for the dinner-party. Harry heard him coming, and poked his head out of the door of his room. ‘Well, did he buy supplies?’

‘Yes!’ replied Fane. ’Two bottles of sherry! And you’re to be cautious with it! He had one in one pocket and one in the other, and he told me to warn you!’ Such a jest as this was naturally far too good not to be passed on, and when the party assembled in Skerrett’s dining-room, both Barnard and Colborne were let into the secret. The dinner was quite as bad as Tom had expected it to be, but everyone agreed that it was a splendid party, because no sooner had the company sat down to table than Colonel Barnard said: ‘Come, Smith, a glass of wine!’ in the blandest way. The sherry from Lesaca disappeared before the first course was served, and Tom Fane had to retire into the background to struggle with himself.

‘Now, General, some more of this wine!’ said Barnard. ‘We camp fellows don’t get such a treat every day!’

Colborne’s grave, fine mouth twitched, for he had dined with Colonel Barnard. Skerrett, glaring at Harry, said: ‘I very much regret to say that is the last of an old stock, Barnard. What I must now give you, I fear, won’t be so good.’

It was, in fact, black strap. Barnard said: ‘No, that won’t do, but let us have some brandy!’ But black strap was all they got, and no brandy made its appearance, even when some very bad coffee was served to round off General Skerrett’s first and last dinner-party. ‘You are wicked fellows, all of you,’ Colborne said afterwards, with the smile that only lit his eyes. ‘If ever I get a brigade, I hope they don’t send me you for my Brigade-Major, Smith.’ ‘When you get your brigade, I hope I may be your Brigade-Major, Colonel!’ replied Harry quickly.

6

On the 25th August, the regiment’s birthday, the officers of the 95th Rifles held their first regimental dinner, a very different affair from Skerrett’s memorable feast. No less than seventy cheerful gentlemen sat down to dinner, and since the whole division was in bivouac, and there was no house in the vicinity with a room large enough to accommodate such a party, it was decided to hold a strictly alfresco entertainment. Two long, deep, parallel trenches were dug; the gentlemen sat on the ground with their legs in these, and the greensward between them served as a table. Anything less solid, Molloy said, would have collapsed under the weight of food and drink spread upon it. It was a noisy, cheerful party, with plenty of toasts, and a good deal of singing; and the French outposts, on the height overlooking the scene, watched it all with the keenest interest; A few days later, volunteers were called for to help in the second assault on San Sebastian. It was rumoured that Lord Wellington had said that he would send troops to San Sebastian who would show the 5th division how to carry a town by storm: a remark not calculated to please soldiers who had failed to accomplish an impossible task. Lord Wellington wanted a hundred and fifty men from the Light division, besides several hundreds from other divisions; but when forty volunteers were asked to step out from one battalion, the whole battalion took a pace forward. In the end, the forty were selected, but there was a good deal of quarrelling between the men; and officers, clamouring in vain to be chosen, nursed bitter grievances for days. However, the successful volunteers got a very cold welcome from the Pioneers, when they reached San Sebastian; and General Leith said roundly that so far from showing the 5th how to mount a breach, they should act as supports, not as the forlorn hope. The date of the storm was fixed for the last day of August, but it was expected that Soult would make an effort to relieve the town. His army was known to be concentrated between the coast town of St Jean de Luz, and the village of Espelette, so Lord Wellington was quite ready for him, on the western side of the Bidassoa. Near the coast, there were fords at Irun and Behobie, but everywhere else in the district the river was very inaccessible, with steep, rocky banks, affording no facilities for the crossing of an army. On the Upper Bidassoa, at Vera, the Light division still held the town with pickets, the body of the division being encamped on Santa Barbara, looking slantways down upon the town, and the barricaded bridge. The Portuguese attached to the 4th division were guarding the fords lower down the stream, but when Soult moved in force, very early on the morning of the 31st August, one of the all too frequent mountain fogs hung heavily over the river, so that nothing could be seen of an enemy advance. Four divisions, under Clausel, attacked the Portuguese before seven o’clock, and crossed the river in the dense haze. This-lifted about an hour later, and a French battery began at once to shell Vera, from which the Light division withdrew its pickets. The division, drawn up in battle array on the commanding ground above the town, expected to be attacked in force, but it soon became evident that the main attack was being launched on the Lower Bidassoa, where General Freire’s Spaniards (with two British divisions m support) had the honour of receiving the frontal onset. By ten o’clock, that affair was at an end, the Spaniards behaving very well, but losing heart a little towards the end of the struggle. General Freire, very nervous, went in person to Lord Wellington to beg for reinforcements, but his lordship replied coolly: ‘If I sent you British troops, it would be said that they had won the battle. But as the French are already retiring, you may as well win it by yourselves.’

Meanwhile, some miles farther upstream, at Vera, the Portuguese continued to be engaged all day, in the most miserable weather. It rained incessantly, and some threatening growls of thunder, and sudden squalls of wind, indicated that a tempest was brewing. The river was rising rapidly, a circumstance which soon made Brigade-Major Smith uneasy, for if the fords became impassable it was obvious that the French must, for safety’s sake, try to possess themselves of the bridge at Vera. When the heavy cannon-fire drove back the British pickets from the town, Harry galloped at once to where Skerrett was standing, in a most exposed position, beside his horse, and pointed out to him the preparations being made by the enemy for an attack upon the cluster of houses, held by some Riflemen, at the bridgehead. Harry, who was already exasperated by Skerrett’s apparently fixed habit of choosing a dangerous place to stand in while his men cleverly concealed themselves in every available scrap of cover, spoke impetuously, and with a good deal of impatience. ‘General Skerrett, unless we send down the 52nd regiment in support, the enemy will drive back the Riflemen! They can’t hold those houses against the numbers prepared to attack. Our men will fight like devils, expecting to be supported, and when they’re driven out their loss will be very severe!’

He had to shout to make himself heard above the noise of shell-bursts, and, indeed, expected to be hit momently, since every kind of shot was peppering the ground all round his General. Skerrett seemed to be as unconcerned at his warning as at the gun-fire, and laughed. ‘Oh, is that your opinion?’ he said.

‘And it will be yours in five minutes!’ retorted Harry insubordinately.

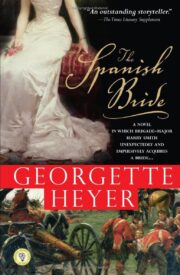

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.