But however much treasure his lordship’s troops had plundered, and however many bottles of wine they had drunk, none offered the least violence to any of the distracted French or Spanish civilians, who had been abandoned by the flying army. There were many women and children amongst these, some of the children were quite lost, and wailing dismally for their mothers. They were comforted by being fed on all the most unsuitable foods found amongst the French baggage-train; and the Comtesse de Gazan’s little boy, not apparently at all dismayed by the loss of his parent, was actually adopted by one soft-hearted soldier. He was later discovered, and returned, protesting loudly, to his mother, who had, to do her justice, signified her complete willingness to relinquish him to his new protector. When the division, which led the centre column, began their march along the Pampeluna road, their progress, like that of the rest of the army was slow. The soldiers were tired, and they had been gorging themselves on roast mutton, having captured some flocks of the enemy’s sheep, and killed :and eaten them. Nearly every man’s haversack was found to be weighed down with pilfered flour, and large joints of fresh-lolled mutton, and when this booty was thrown away, which it soon was, the brigades were able to march a little faster. Ahead of the infantry, Victor Allen’s horse were harrying the French rear-guard, and rounding up the stragglers. His lordship complained that his men were so fagged-out that he had no fresh troops to send forward to cut off the ragged retreat, but there were a great many Colonels who would have hotly refuted this accusation, had they known of it The number of prisoners taken during the battle had been ridiculously small: a fault, said the infantry, to be laid at the cavalry’s door.

The weather was appalling. Thunder rolled incessantly, and the rain came down in torrents, turning the causeway in some places into a swamp through which the swearing troops had to wade knee-deep. A steep climb, and a sharp descent through a defile led to Salvatierra, where all roads met, and the right and left columns were obliged to join the centre column. Ahead, the mountains of Navarre seemed to bar the way.

There was a change in the order of the march during the afternoon, his lordship, on his Quartermaster-General’s advice, directing Graham, with the greater part of his force, to march north, towards the great Bayonne chaussee, cut during the battle by Longa’s Spanish troops. Finding and diverting Graham’s men on an afternoon of drenching rain and low mists was no easy task; there was a good deal of confusion; and some of the advanced cavalry did not receive the orders until nightfall. Wellington’s temper, said his Staff, was getting worse. He was snapping at everyone, and before the day ended he had found a scapegoat. Through the damp bivouacs that evening, an incredible piece of news flew from camp-fire to camp-fire: his lordship had placed Norman Ramsay, his most brilliant artillery-officer, under arrest, for having misunderstood an order given to him by his lordship in person. No one, from private to General, who had seen Ramsay burst through the mass of the French infantry at Fuentes de Ofioro, at the head of his battery, could hear such news unmoved. The army forgot its grievances in indignation. Nothing else was talked of, and the epithets used to describe his lordship were anything but flattering. Anson, to whose brigade Ramsay was attached, represented to his lordship what splendid work he had performed on the previous day, at Vittoria; quite a number of senior officers took their courage in their hands, and interceded for him; but his lordship was implacable. The discipline of the whole army was lax, and he meant to make an example of Captain Ramsay.

6

All next day the army plodded and waded its way along the road to Pampeluna. Only Victor Alten’s cavalry was in touch with the French rear, progress being delayed by the firing by the French of every village they passed through. Staff-officers, who had been privileged to hear Lord Wellington’s opinion of his troops, thought privately that in face of the ravages being committed by the enemy all along the line of the retreat his strictures might have been spared. The most dreadful scenes of desolation were everywhere seen. The country people had fled from their burning cottages to cower in the woods and orchards; farm animals lay bayoneted to death amongst the charred ruins of barns; and once the sad little corpse of a baby made the soldiers take firmer grips on their shouldered muskets, and march on at a quickened pace, in silence, and with gritted teeth. Very little was heard about hard going, wet clothes, and blistered feet. The army wanted only to come to grips with the enemy who had created this monstrous desolation.

The Riflemen of Kempt’s brigade, supported by Ross, and Arentschildt’s Hussars, came to grips with them on the following day, at Yrurzun. It was only a skirmish at the bridge of Araquil, but the Rifles felt much better after it. They captured one of the only two guns rescued from Vittoria, and the and brigade said enviously that Kempt’s fellows had all the luck. But the Enthusiastics, closely following the Light division on the march, damned all Light Bobs impartially, and said that it was time someone else had a chance to be first in the field.

The Light division bivouacked within sight of the walls of Pampeluna that night. The town looked rather imposing, situated on a hill in the middle of a treeless plain, on the left bank of the Arga, but no one had any opportunity of exploring it, since it was strongly fortified, and held by a French garrison. On the following morning, news that Clausel was in the vicinity, trying to effect a junction with King Joseph’s force, reached Wellington, and the Light and 4th divisions were suddenly ordered to march south, taking the mountain road to Tudela. Vandeleur’s brigade reached the little village of Offala, after a difficult march, and as a sharp look-out had to be kept towards Pampeluna, Harry lost no time in finding a likely-looking guide. He and Vandeleur posted the pickets together, and the guide was found to be both knowledgeable and chatty. Since Vandeleur spoke no Spanish, Harry bore the burden of the conversation. The guide, like everyone else, was full of curiosity about the battle fought at Vittoria, and after asking Harry a great many questions, he whispered with a jerk of his head in Vandeleur’s direction. ‘What’s the name of that General?’

‘General Vandeleur,’ replied Harry, wondering what was coming next. ‘Bandelo, Bandelo,’ muttered the guide, apparently committing it to memory. ‘Excuse me, señor!’

He bestowed an engaging smile upon Harry, and running forward to where Vandeleur was riding a little ahead, besieged him with a flood of conversation.

‘Here, Harry, I want you!’ called Vandeleur. ‘What’s the fellow saying?” ‘He is telling all he heard from the Frenchmen who were billeted in his house during the retreat. He’s full of anecdote.’

‘Oh, is that all?’ said Vandeleur.

The guide, his expressive eyes searching first Harry’s face and then the General’s, as though in an attempt to read the meaning of their English speech, said earnestly: ‘Yes, they say the English fought well, but had it not been for one General Bandelo, the French would have gained the day!’

‘Why does he keep staring at me?’ demanded Vandeleur. ‘What does he say now?’ Without as much as a quiver of a smile, Harry translated the guide’s remark. ‘Upon my word!’ Vandeleur said, much struck. ‘He must mean our going to support the 7th! Now, how the devil did he know?’

‘Can’t say, sir,’ said Harry gravely.

‘He’s an intelligent fellow,’ said Vandeleur. ‘Here, you, catch!’

The guide caught the coin tossed to him with the most extravagant expressions of gratitude, and turning, winked broadly at Harry.

When they returned from posting the pickets, Harry discovered that the guide was his landlord for the night. He promised to provide an excellent dinner, and when Harry was hunting for a clean shirt in his portmanteau, he came up to tell him, with a great air of mystery, that he had some capital wine in his cellar, as much as Harry and his servants cared to drink. ‘You come down and look at my cellar, señor,’ he said. ‘You will be surprised!’

‘Yes, but I’m dressing,’ answered Harry, rather impatiently.

‘No, come!’ insisted his host. ‘I will show you what I have downstairs! You will be pleased!’ ‘What a strange man!’ Juana said, in French. ‘I don’t like him. I wish you would send him away.’

‘He’s too damned civil by half. I suppose I shall have to go. I hope he really has got something worth having in his cellars.’

He followed the Spaniard out of the room, and waited at the head of the stone stairs leading down to the cellars while he lit a lamp.

‘Now!’ said the man.

The note of suppressed excitement in his voice made Harry look up sharply. He thought there was an odd expression in Gonsalez’ face, but it was not until he was half-way down the stairs, and his host turned to speak to him, holding the lamp up, that he realized that the most extraordinary change had come over the man. His smiling countenance looked positively fiendish, and his eyes glanced sideways at Harry in the most sinister fashion imaginable. He was a big, muscular fellow, and Harry was unarmed, his servants out of earshot.

‘Come, señor!’ urged Gonsalez. ‘You are about to see a wonderful sight! It will gladden your heart, and because you are English, I will let you feast your eyes on it.’ ‘Lead on!” said Harry lightly.

It was dank and chilly at the bottom of the stairs; Gonsalez fitted a key into the lock of one of the doors, turned it with a grating noise, and flung open the door, holding the lamp so that its beams lit up the cellar. ‘There, señor!’ he said, in a demoniacal voice. ‘There lie four of the devils who thought to subjugate Spain!’

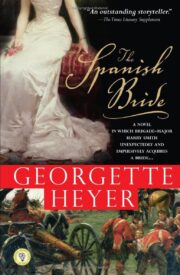

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.