He brought in the news that one of the French General’s wives, Mme de Gazan, had been found by Mr Larpent, stranded in a carriage from which the horses had been stolen, and loudly bewailing the loss of her little boy. Larpent had escorted her to Vittoria, of course, and as soon as she found that she was to consider herself Lord Wellington’s honoured guest, her spirits revived, and she seemed to be in a fair way to forgetting the loss of her child. ‘What’s she like? Pretty?’ inquired Vandeleur’s ADC.

‘I don’t know, I didn’t see her. Johnny Kincaid’s in luck again: his fellows found a whole case of wine in some old gentleman’s private carriage. I left Johnny drinking the old man’s health. I’ve never seen anything like the mess all over the roads and the fields! They say the whole of Joseph’s private loot is lying about to be picked up by our plunderers. I myself saw a couple of fellows stuffing their pockets with doubloons.’

‘Not ours?’ Vandeleur said quickly.

Harry shook his head, and refrained from telling his General that one of these pilferers had been an officer.

It was growing dark, and as no one’s baggage had come up there was no means of lighting the barn. The batmen had found some forage for the horses, and had procured a tin kettle, which was boiled over a fire kindled at one end of the barn. Supper was eaten by the flickering firelight, and everyone was so tired that as soon as the last mouthful had been swallowed, they all lay down amongst the horses, wrapped in their cloaks, and slept as soundly as if they lay on the best feather-mattresses. Juana was entirely unembarrassed by a situation which would have made any English lady faint with horror. Having had no other experience of life outside convent walls than that which she had gained at Harry’s side, she saw nothing put of the way in sharing sleeping-quarters with half-a-dozen horses, and several Staff-officers. If she had thought about it at all, she would have supposed that every married lady who followed the drum did the same. It would not, of course, be approved by of her own countrymen, but if one was married to an Englishman one’s whole way of life was naturally peculiar. She was young enough to think it very good fun to comb out her tangled curls with the General’s pocket-comb, to wash the dust from her face and hands in a tin pannikin, and to dry them on the ADC’s handkerchief, which happened to be the only clean one to be found amongst the company.

By daybreak, the baggage, thanks to Surtees’s indefatigable exertions, had arrived, and, the various canteens having been unloaded from the mules’ backs, everyone, including Vandeleur, who tried to toast slices of bread on the end of his sword at a smoky fire, set about preparing breakfast. But hardly had the kettle begun to boil than orders came for the divisions to fall in. Everything had to be packed in a hurry, and the horses saddled-up, and led out of the barn. The General had already mounted, and Harry was shouting to Juana to make haste, when she suddenly stopped in the doorway of the barn, and said: ‘Listen! I am sure I hear someone moaning, like a wounded man!’

‘Nonsense, come along!’

‘But I do hear it!’ she insisted.

‘Better take a look round,’ grunted Vandeleur.

Harry went back into the barn, and glanced about him rather impatiently. He discovered that there was a hay-loft over half the barn, which, in the dusk of the previous evening, no one had noticed. As he looked round for the ladder, a stifled groan sounded unmistakably. There did not seem to be a ladder, or else it had been hauled up, but with a little help from Vandeleur’s ADC Harry managed to scramble into the loft.

The most unexpected sight met his eyes. Upwards of twenty French officers, all badly wounded, and one poor devil dying fast, as Harry saw at a glance, lay huddled there on the heaped hay. A woman was bending over the dying man; when Harry hoisted himself into the loft, she looked up, putting back the hair from her brow with a shaking hand. Her expression was distraught; as she stared at Harry, a little pug-dog ran out from the shelter of her skirts, and began barking at him. Nobody spoke; several of the officers were lying in a state of semi-coma; and one, who was sitting up with his back against the wall, seemed hardly to be aware of Harry’s arrival. The woman crouched over the dying man, as though trying to shield his body with her own. Harry stepped forward, addressing her in French. She answered in Spanish, and very disjointedly. He noticed that some of the men lying all round in the hay were watching him with wary, suspicious eyes, and spoke to them, assuring them of every attention. The lady, who seemed to be growing gradually less afraid of him, begged him to do something for her lover. Harry knelt down beside the man, but his face was livid, and his eyes beginning to glaze. ‘I am sorry,’ Harry said awkwardly.

She gave a moan of despair, and cast herself upon the dying man, passionately kissing his lips. The dog, which had been sniffing at Harry’s boots, began to jump up at him, all the little bells on its collar tinkling merrily.

Harry got up, and, seeing the ladder lying near the edge of the loft, lowered it into the barn, calling to Juana to come up.

‘Tell the General, Bob!’ Harry said. ‘We’ll need a guard to take ’em in charge, but they’re all of them wounded, and we ought to do something for them. Send a couple of fellows up to me, and West too!’

Juana, handed up the ladder, was dreadfully shocked by the sight of the wounded men, and the thought that they had lain there all night, stifling their groans for fear of the English officers beneath them. She ran at once to the Spanish lady, tears of sympathy springing to her eyes. The officer was dead, and for a little while it was impossible to coax the lady away from his body. She sobbed out that he had been so thirsty, and she had had no water to give him, which made Juana cry in great distress: ‘Oh, señora, if we had but known! Alas, alas!’ The General having sent in a couple of orderlies, Harry was having the wounded men lifted down into the barn. They seemed at first very much alarmed, as though they dreaded their fates at the hands of their enemies, but when they had been given water and brandy to drink, they began to be better, and were able to reply with tolerable composure to Harry’s assurances of kind treatment. They were all of them quite young men, hardly more than boys, and the dreadful defeat of the previous day, followed by a night spent in pain and thirst, had distorted their imaginations. The breakfast, which had been stowed away in the canteens, was quickly unpacked again, and given to as many of the prisoners as were in a fit state to eat it; and the Spanish lady, seeing Juana bathing and binding an ugly wound on one officer’s leg, roused herself from her grief, and tottered over to help her. It was impossible for Harry to linger, but by the time the guard had arrived, the worst wounds had been roughly attended to, and several of the officers were sitting up, eating slabs of ham and bread, and feeling very much better. They were all of them embarrassingly grateful, particularly the lady, who caught up her little pug, and put her into Juana’s arms, begging her to accept her in return for her kindness.

Juana was charmed with the dog, a pretty little creature with a coat like satin, and the most engaging tricks, but she hesitated to take her.

‘No, no, I beg of you!’ the lady insisted. ‘She is very good, very intelligent. I wish you to take her! If you would give me pleasure, do not refuse!’

‘Oh, Enrique, may I?’ Juana said, turning a pair of starry eyes towards him. Did it occur to Brigade-Major Smith that a lap-dog would scarcely be a welcome addition to his baggage? Not for a moment! Of course Juana might take the little thing, and a dozen more like her, if she chose!

‘Now what in thunder have you got hold of here?’ demanded the General, when he saw the pug-dog precariously mounted on Juana’s saddle-bow.

Juana let the reins drop to hold up her pet for inspection. ‘Oh, dear General Vandeleur, my perrilla! Look, is she not a darling dog? I am going to call her Vittoria! My little Vitty, are you not, mi querida?’

5

Although the division had been ordered to fall in by ten o’clock, they did not, after all, march until noon. There was much to be done to clear up the inevitable confusion resultant upon such a victory. The wounded had to be established in Vittoria; the dead had to be decently buried; and every regiment suspected of plunder was made to line up its kitbags for inspection.

His lordship, whose plans to encircle and annihilate King Joseph’s army had miscarried, owing partly to Graham’s failure to push home a vigorous attack from the north, and partly to Dalhousie’s dilatoriness, was in the vilest of tempers. Yet although over fifty thousand Frenchmen had managed to escape from the field, every one but two of their cannons had fallen into his lordship’s hands, and not even Salamanca had been such a smashing victory. The King had fled, and his army was straggling after him, all the divisions but Reille’s in a state of disastrous disorder; and their objective was France, where only the King could think himself safe. But none of this made his lordship better-tempered. A large preponderance of his devoted troops had spent the night following the battle not in getting much-needed rest and food, but in searching the ground for plunder. The twinkling of many lanterns had made the stubble-fields beyond Vittoria look like a fair-ground, and naturally all the cases of wine had been disposed of, so that a number of good soldiers, when the order to fall-in was blared out on the trumpets, were sleeping the sleep of the totally drunk in ditches and under hedges. Some waggish (souls, finding the uniforms of French officers amongst the I baggage, had dressed themselves up in these, a jest not exactly calculated to appeal to their Commander-in-chief’s sense of humour. But worse than these excesses was the disappearance of the greater part of King Joseph’s treasure. Though priceless pictures, cut from their frames and rolled up in special containers, were to be found stowed away in the royal coaches, or spilled out of burst chests; though silks and brocades were packed layer upon layer in strong boxes; and silver chalices, candlesticks, and pieces of gold plate were dragged out from under carriage-seats; though more than a hundred and fifty pieces of cannon had been captured, an Eagle, a stand of colours, and no less a trophy than Marshal Jourdan’s baton (which his lordship sent off to the Prince Regent, with his humble duty); only one-twentieth of the money sent from Paris came into his lordship’s custody. ‘The soldiers of the army have got among them about a million sterling in money,’ wrote his lordship bitterly, to Earl Bathurst. The search through the kit-bags failed to discover the missing treasure. His lordship said that the battle had totally annihilated all order and discipline. The rank-and-file were composed of the scum of the earth; the non-commissioned officers were as bad; and none of the officers performed any of their duties. ‘It is really a disgrace to have anything to say to such men as some of our soldiers are,’ wrote his lordship, but, happily, for Earl Bathurst’s private consumption only.

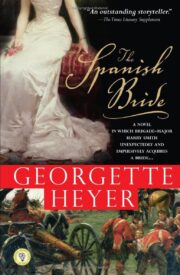

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.