‘Well, and how is our acting Adjutant?’ inquired Stewart. ‘Dined, Johnny?’ ‘If he hasn’t, he can’t dine here,’ said Harry. ‘He can’t even have any port, because-oh yes, he can! I’ve got a mug somewhere! Stretch out a hand and feel in that case behind you, Young Varmint! A beautiful mug from Lisbon-that’s it.’

‘Port? You haven’t got any port!’ said Kincaid, hope battling with suspicion in his face. ‘Don’t think to fob me off with any Portuguese stuff! I’ve been dining with the Colonel.’ ‘Exalted, aren’t you?’ said Molloy. ‘Don’t waste the port on him, Harry!’ ‘By God, it is port!’ exclaimed Kincaid. ‘Where the devil did you get it, Harry? Old Cameron gave me black strap!’

‘Elvas,’ replied Harry. ‘The Beau himself hasn’t any better.’

‘The Turk!’ said Kincaid, raising the Lisbon mug in a toast to the army’s most famous sutler. ‘I thought you must have got it by wicked plunder.’ ‘He probably did,’ said Molloy. ‘You haven’t got any money, have you, Harry? Not real money?’

No, Harry had no money, but he had borrowed three dollars from the Quartermaster, after the fashion of all hard-pressed officers who had several months’ pay owing to them. But the two skinny fowls which had formed the major part of the dinner had been almost certainly dishonestly come by, since they had been provided by his servant, who was an experienced campaigner.

‘That man of yours will be hanged one of these days,’ prophesied Stewart. ‘What’s the news, and where have you been, Johnny?’

‘No news, except that Leith’s fellows are going to try the river bastion.’ ‘We know that! Talk of forlorn hopes! The men say if the Light Bobs and the Enthusiastics can’t take the town, there are no troops that can. I suppose the hour’s been changed to suit the Pioneers. I thought all the ground in front of the river bastion was mined?’ ‘Captain Stewart will now move a vote of censure on his lordship’s plans,’ said Molloy, looking round for somewhere to throw the butt of his cigar. ‘Unless I can stub this out on Young Varmint’s boot, I shall have to get up and go.’

‘Well, go, then,’ said Havelock. ‘I’ll have you know these boots of mine are the only ones left to me. Besides, there’ll be more room with you gone. Oh, by God, will there, though! Here’s George!’

The officer peeping into the tent was a somewhat stout young man, with a serious face that matched a certain sobriety of outlook. He had entered the army in the expectation of being enabled to assist in the support of his numerous brothers, a prospect that might well have appalled a less earnest man, and did indeed prevent Mr George Simmons from sharing his friends’ lighthearted spirits. He was a little prone to moralize, but he was a good officer, and a faithful friend, and the company assembled in Harry’s tent greeted him with affectionate ribaldry.

‘No, I mustn’t stay,’ he said, shaking his head. ‘I just heard you fellows funning, and I thought I would look in on you. I’ve been talking to one of Beresford’s Staff. Would you believe it?-one of Beresford’s ADCs had the abominable bad taste to remark at table just now that he wondered how many of those present would be alive tomorrow! You can imagine what a look the Marshal gave him!’

His shocked countenance made Harry’s guests laugh, but Harry said quickly: ‘Damned young fool! Who was it?’

‘No, it wouldn’t be right to tell you. I daresay he is sorry now. It’s very strange, the inconsiderate things a man’s tongue will betray him into saying.’ ‘Not yours, George, not yours!’ said Kincaid, getting up.

‘Well, I do hope it does not, for such observations as that are bound to produce some gloomy reflections,’ said Simmons.

5

Dusk, and the consequent slackening of gun-fire in the distance, soon made Harry’s guests glance at their watches, and bethink them of their duties. The party began to disperse, the host being the first to leave. If the story told by George Simmons had produced gloomy reflections in the minds of his auditors, not one of them gave any outward sign of an inward discomposure. They wished one another luck; they cracked a parting joke or two; and very close friends exchanged handshakes that perhaps expressed something more than the light words they spoke.

The night was dark, but quite dry, though the sky was heavily clouded. The Light and 4th divisions had to march down the ravine that lay to the east of the Pardeleras hill, and as they approached the trenches the air grew vaporous with the unhealthy river-exhalations. The storming-parties, conducted by the Engineers, trod softly, all talking being hushed in the ranks, since it was vital to the success of Lord Wellington’s plans that every one of the five attacks should be launched simultaneously. Even the trench-guards were unusually quiet; there was nothing to be heard from the trenches but a low murmuring noise. It was difficult marching, when no one could see more than a couple of paces ahead, but Badajos could be located by the little bobbing lights that moved along the ramparts. Someone whispered that Lord Wellington had taken up a position on the top of the quarry, from where he could observe the progress of the main attack, but it was too dark for even the most eagerly straining eyes to pick out his well-known figure in the surrounding murk. The men liked, however, to know that he was watching their exploits. It put them on their mettle, and gave them an added confidence, for though he was a cold, often a harsh, commander, he was one who knew his business, a man one could put one’s trust in.

The river-mist was cold, and grew thicker as the storming parties crept up the slope of the glacis. From the ramparts, the sound of an isolated voice, loud in the stillness, drifted to the besiegers’ ears. It was only the usual, warning Sentinel, gardezvous! that was quite familiar to troops who had all done trench-duty outside the walls, but in the darkness and the quiet it sounded unaccustomed, rather fateful.

Colonel Cameron, and Johnny Kincaid, his Adjutant, having reconnoitred the ground by daylight, the services of the Engineers were not much needed to conduct the storming-parties to their positions. The men stole up the glacis, through the haze, and lay down as soon as they got into line, the muzzles of their rifles projecting beyond the edge of the ditch, ready to open fire. The clouds were parting overhead, permitting a little faint moonlight to illumine the scene. The Light troops, staring up at the walls of Badajos, which seemed to rise sheer out of the river-fog, could see the head of the Frenchmen lining the ramparts. A sharp qui vive? from one of the sentries was followed by the report of a musket, and the noise of drums beating to arms. Colonel Cameron, commanding the four companies of the 95th Rifles which were already extended along the counterscarp to draw the enemy’s fire, stole up to Barnard. ‘My men are ready now: shall I begin?’ Barnard was giving some low-voiced instructions. He had his watch in his hand, and a wary eye upon the men of the ladder-parties, who were gently lowering the ladders into the ditch, between the palisades. No fear that Barnard would strike before the hour. ‘No, certainly not!’ he said under his breath.

The storming-parties were still creeping up the long slope to the edge of the glacis, when in the distance, to the east, the sky was suddenly lit by a flaming carcass, shot into the air. This was followed almost immediately by the roar of cannon-fire, mingled with the sharp crack of musketry. The time was a quarter-to-ten only, a circumstance that made Barnard curse softly. It was evident that the approach of Picton’s escalading parties must have been seen from the Castle, since it was unthinkable that Picton could have wantonly opened the attack before the appointed hour. While the last of the storming-parties of the Light and 4th divisions were stealing up the glacis, the darkness away to the right was lit by lurid bursts of flame; and the cannon-fire momently increased, until it seemed to the men crouching above the ditch that every gun in Badajos must be trained on to the very forlorn hope assailing the precipitous Castle-hill. What accident had occurred to discover the 3rd division’s stealthy advance to the French could only be a matter for conjecture, but that Picton, finding that his movements had been seen, had launched his attack a quarter-of-an-hour before time, was soon apparent.

O’Hare, commanding the 95th storming-party, was fretting to give the word to advance, but was too old a hand to betray his impatience to the men watching him so eagerly. Barnard was as cool as if upon a field-day; but Cameron, waiting beside him, could scarcely contain himself. His party, he was convinced, had been seen by the French on the ramparts, who were now silently watching them. He expected his men to be under fire at any moment, and could not bear to keep them inactive until it should please the enemy to open on them. But Barnard was watching the stealthy ladder-parties. Once he sent Harry Smith to hurry a party that was a little behind the others, but he gave his orders in a quiet unagitated voice, and seemed not to be paying any heed to the gunfire and the rockets on the eastern side of the town.

The last ladder was in place as suddenly, deep and melodious, and quite audible through the noise of the cannons, the Cathedral clock within the town began to strike the hour. ‘Now, Cameron!’ called Barnard.

6

The volley from the British troops was answered by the crash of such a fire as even the most hardened soldiers had never before experienced. A flame, darting upward, disclosed to the besiegers the horrors that lay before them. The storming-parties were some of them swarming down the ladders, and some, too impatient to await their turns, leaping down on to the hay-bags dropped into the ditch to break their fall. There, fourteen feet below the lip of the glacis, every imaginable obstacle, from broken boats to overturned wheelbarrows, had been cast to impede the progress of the attackers. All amongst them, wicked little lights burnt and spluttered. George Simmons, trying to stamp out one of these, was jerked away by a friend. ‘Leave it, man! leave it! There’s a live shell connected with it!’ The roar of an explosion drowned the words; somebody screamed, high and shrill above the uproar; a fire-ball was thrown from the ramparts, casting a red light on the scene. Men were pouring down the ladders into the inferno of bursting shells in the ditch; within a few minutes the ground was further encumbered by scores of dead and dying men; and the most horrible stench of burning flesh began to be mingled with the acrid smell of the gunpowder. Every kind of missile seemed to rain down upon the stormers. The air was thick with splinters, and loud with the roar of bursting shells, and the peculiar muffled sound of muskets fired downwards into the ditch. The Engineers, whose duty it was to lead the storming-parties, were shot down to a man. The troops, choked by the smoke, scorched by the flames, not knowing, without their guides, where to go, charged ahead to the one breach they could see, only to fall back before defences more dreadful than they had ever encountered. The breach was covered from behind by a breastwork; the slope leading up to it was strewn with crowsfeet, and with beams, studded with nails, that were hung from the edge of the breach. The men struggled up, fast diminishing in number as man after man was shot down by the steady fire maintained by the defenders behind the breastwork. But when the obstacles on the slope had been passed, the breach was found to be guarded by a hideous chevaux-de-frise of sword-blades stuck at all angles into heavy timbers that were chained to the ground. Those behind tried to thrust their foremost comrades forward; someone flung himself down on to the sword-blades in a lunatic endeavour to make of his own writhing body a bridge for the men behind him. It was in vain. While his brains were beaten out by the butts of French muskets, the storming-party was hurled back in confusion, into the indescribable hell below. Powder-barrels, rolling down upon them, exploded with deadly effect; from the breastwork the exultant French were shouting mockery and abuse, while they poured in their volleys.

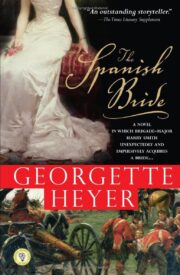

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.