A glance at the map spread out on the table at Alten’s headquarters was enough to show Harry that the field was a larger one than had yet been fought over. His lordship’s plan was to launch his army in four masses upon the French, an operation requiring the nicest of timing. Hill, working round the outside of the French left, was to cross the Zadorra, and to storm the heights of Puebla, a range of hills almost at right angles to the Allied front; and from there to descend with his main body by a defile on to the plain, while his flank thrust its way along the heights. While these operations were in progress, the Light and 4th divisions were to form before the two bridges of Nanclares, and to remain there, hidden from the enemy by the rugged nature of the ground, until Hill should have gained the Puebla heights. North-west of them, on the same front, the 3rd and 7th divisions would march over the high Monte Arrato, descending on to the plain near the Mendoza bridge, upstream from Nanclares, and just beyond a more than usually sharp bend in the river. Lastly, Graham’s column, masked by Spanish infantry, was to fall on Sarrut’s division on the extreme French right flank. In this way, the Allied army would, roughly, attack the enemy on three sides of a square.

Since the 20th June was spent by the army in getting into order, Harry was fully occupied, and had little time to spend with Juana. Brigade headquarters were in Pobes, a picturesque but filthy village which afforded nothing but bug-ridden cottages as billets for the Staff. There were so many fleas on the mud-floor in the Smith’s low-roofed room that Juana spread her bedding on the table, and curled herself up on it. A couple of centipedes, wandering out from under a cupboard, added nothing to her comfort. She slew them with the butt of her riding-whip, but they proved to be very tenacious of life, and the execution ended with Juana’s feeling rather sick. When Harry came in to supper, it was late, and he was frowning over his orders. A grunt was the only answer he vouchsafed to a tentative remark, so Juana, who never took offence at being neglected in the army’s cause, ate her supper in patient silence.

‘What awful stuff!’ Harry said, chewing some leathery beef. ‘Yes,’ Juana agreed. ‘I could make an omelette for you, if you would like it.’ ‘No, it’s of no consequence,’ he replied, fork in one hand, and map in the other. He went off to Vandeleur’s headquarters after supper. When he returned, Juana was lying wrapped in a blanket on the table, wide-awake, and rather anxious. She smiled at him, but he was not deceived, and said at once: ‘Hallo, there! Now, what business has that scared face in my quarters?’

Juana sat up. ‘Don’t be angry with me! I cannot help being a little afraid, I find.’ Harry hung up his wet cloak, and came over to the table. ‘Afraid? You? Que dira la gente?’ ‘I do not care.’

‘Well, I hope you care for what I say! You are a bad, stupid child. How many actions do you suppose I have taken part in?’

‘You know very well that has nothing to do with it. I wish you were a Go-on, and not a Come-on!’

‘Por gratia! Do you? Do you indeed?’ ‘No,’ sighed Juana.

‘Just as well!’ said Harry, kissing her cheek. ‘Go to sleep now, querida: I must get some sleep too.’

There were a great many questions she wished to ask him, but he was still looking preoccupied, so she asked only the most important. ‘When do we march?’ ‘What? Oh!-early. But you’ll stay here with West.’

She sat hugging her knees, staring rather hard at a chair directly before her. ‘It is a little melancholy, having to wait in the rear.’

He smiled, but shook his head. ‘No use, Juana: you can’t come on to the field with me.’ So when the Light Bobs moved off on the following morning, a disconsolate figure in a much worn riding-dress stood in the doorway of the cottage to watch them go. The parting with Harry had not been at all romantic. He had been in a hurry, jumping up from the breakfast-table, after a glance at his watch, with his mouth full, snatching up his coat and cocked-hat from a chair, giving his wife a quick hug, and saying in a voice thickened by bread and meat: ‘Take care of yourself! West will see to you.’

He had ridden off on the only one of his horses fit for duty, a nervous, obstinate animal, not yet accustomed to military service. Juana was thinking about that horse as she stood fluttering her handkerchief to the soldiers tramping past. If Harry had been riding Old Chap, the hunter James Stewart had given him, she thought she would not have felt so anxious. She let her hand fall to her side, and stood leaning against the door-post, still watching the column go by. She felt very much oppressed, and began to wonder how many of the Green-jackets moving down the road would be killed, and how many mutilated by horrible wounds. It seemed strange that they should be glad to be going to fight, but they were glad, nearly all of them, as you could see by the quickened look in their faces. Suddenly she perceived Kincaid, and in case she should never meet him again, she ran out into the road. He was surprised to see her, for he thought that she would have gone farther to the rear. He was riding beside his company, and reined in at once, stretching down his hand, with an exclamation. She was unable to speak, but pressed his hand, looking up into his face with wet eyes. Before he could say anything, she had run back into the house. Kincaid told his horse savagely to ‘Get up!’ and rode on, a snatch of a poem, once read and almost forgotten, teasing his brain. But he could only remember one couplet, which ran: So highly did his bosom swell As at that simple, mute farewell, which sounded nonsensical, bereft of its context, but went on reiterating in his mind, as such jingles will.

2

By the time the Light division, traversing the high, rocky ground which dropped down to the Zadorra, reached the plain, the vapour had curled away, and the sun had come out. Every feature in the landscape became so sharply defined that distant objects could be discerned as well by the naked eye as by the help of spy glasses. The scene was oddly foreshortened, so that the spires of Vittoria, five or six miles away, looked to be much closer, and it was possible almost to distinguish the leaves upon trees a great way off. The Light and 4th divisions took up positions about a mile back from the Zadorra, where it was spanned by the two bridges of Nanclares. They approached unseen by the enemy, and were ordered to pile arms, and to keep under cover of the hollow road, and the convenient outcrops of rock. They lay down, grumbling good-humouredly at old Douro for having given to Hill the honour of opening the engagement. From various posts of vantage, the officers were able to command a comprehensive view of the whole field, and even to pick out, upon a hill, the figures of King Joseph and his Staff. For a long time, nothing but slight troop movements disturbed the stillness, but shortly after eight o’clock, Harry, who had gone a little way up the steep side of the Monte Arrato, to stare with puckered eyes towards the slopes of the Puebla heights, at right angles to the front, a mile or more away, saw puffs of smoke bursting all along the crest. He waited for a few minutes, and then, as the puffs grew more frequent, and tiny, dark figures appeared on the hill-side, like running ants, he scrambled down from his perch, mounted his horse, and rode back to Vandeleur. ‘General Hill’s come into action, sir.’

‘He has, has he?’ Vandeleur grunted. ‘Where’s my glass?’

It soon became apparent that a sharp struggle between the French skirmishing line and Hill’s Spaniards was taking place on the Puebla heights* Hill sent forward reinforcements, and the gleam of scarlet could be seen beside the dark-coated Spaniards. Wellington, who had been standing in front of the Light division, rode forward to the river-bank to get a clearer view of Hill’s progress. A rumble of artillery fire began to echo round the hills; much larger bursts of smoke appeared on the right, and lifted lazily to disperse in black wisps across the sky.

Suddenly a vicious crackle of musketry in their front drew the attention of the Light Bobs away from Hill’s battle. An aide-de-camp galloped up to Kempt, and desired him to advance his brigade to the bridge at Villodas, a few hundred yards to his left. It was learned that a party of French voltigeurs, perceiving Lord Wellington on the river-bank, had rushed the bridge, seized a wooded knoll on the Allied side of the Zadorra, and opened a brisk fire upon his lordship. No one was hurt, but the shots kicked up showers of mud all round the Staff, and it was clearly necessary to dislodge these intrusive gentlemen. Kempt’s men flung them back on to their own side of the river, and established themselves amongst the shrubs and trees on the bank. Fire flickered all along the line, and wounded men began to struggle to the rear.

‘Catching it, aren’t they?’ remarked Billy Mein, of the 52nd. ‘Hallo, Harry! Any orders?’ ‘Not yet. Hill has taken the heights.’

‘Then what the devil are we waiting for?’ ‘The 3rd and 7th. They haven’t come up.’

‘God knows I hold no brief for old Picton,’ said Mein, ‘but it isn’t like him to be backward in attack. Think anything’s happened?’

‘Dalhousie’s in command, that’s all,’ said Harry.

‘What?’ Mein gasped. ‘Dalhousie put over Picton? For God’s sake, why?’ ‘Nobody knows.’

‘Christ! I’m glad I’m not one of Picton’s lot: he won’t be fit to live with for weeks!’ At about half-past eleven, Kempt’s brigade began to move off by threes to their left. The and brigade watched this manoeuvre with jealous eyes. ‘Here! if we don’t get no sport we’ll get no pie neither!’ an indignant voice from the ranks announced.

‘Hey, why the devil’s Kempt moving?’ demanded Tom Smith. ‘When is it our turn to show our front?’

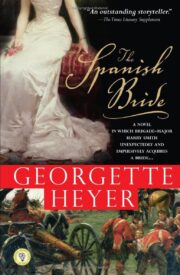

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.