Harry, indeed, had very little time for interference with his wife’s activities. While the division marched as rearguard, his duties were never-ending. It was an anxious time, for Staff-officers; lack of sleep was beginning to make Harry’s eyes red-rimmed, and more heavy-lidded than ever. The army had an uncomfortable time of it on their first day’s march, for the rain fell in torrents, and quagmires on the roads made progress a heavy labour. The Zurgain river, a trickling stream when last seen, had become a raging cauldron of fast waters, and rose to the men’s shoulders as they waded through its fords. There was no halting until after dusk, when the division bivouacked in a dripping wood. Men began to draw comparisons between this retreat and that of Sir John Moore upon Corunna, but when Harry heard them, he laughed. Nothing they could ever suffer again could compare with that hell of snow and ice through which the troops had struggled, by long forced marches, fighting every yard of the way, with boots worn through and clothing in rags, and ice congealing on their unshaven beards. ‘Corunna!’ Harry exclaimed scornfully. ‘Why, you chicken-hearted crew, we covered thirty-seven miles in one day alone then! The men were starving, too!’ ‘Starving, did you say?’ drawled James Stewart, looming up out of the surrounding gloom. ‘Well, so are we now. We’ve lost the Commissariat.’

‘You fellows on the QM staff ought to be shot!’ Harry said wrathfully. ‘What’s happened to it?”

‘Gone to Rodrigo by the northern route.’ ‘It’s not true!’

‘Oh yes, it is!’ said Stewart. ‘Now, don’t blame me! Go and curse the QMG, if you want to curse anyone. His ears should be burning already.’

Although the army had had plenty of opportunity of judging and condemning Colonel Gordon’s inefficiency, no one could be brought to believe at first that the story was true. But no food was forthcoming for the hungry troops, who groped for acorns on the saturated ground, and chewed them sullenly round camp-fires which fizzled damply, and gave out more smoke than heat No one enjoyed much sleep during the night, for only the side of a man’s body which was turned to the fire was warm, and the sticks, collected to make dry mattresses, sank into the mud under the body’s weight. Firing was heard in the small hours and there was an alarm of an enemy attack, which made the men struggle up, groaning for the cramp in their limbs. Nothing could be seen beyond the light of the fitfully burning fires, and it was discovered later that the firing had been caused by some men of the 3rd division discovering a herd of tame pigs in the patch of forest where they lay. The rest of the army, disturbed from its uneasy slumber, denied any share of the fresh-killed pork, was angry with Picton’s ‘black-hearted scoundrels’; and few men had any sympathy for the hangings that took place in the morning.

The army marched at dawn, cold, and hungry, and brittle-tempered. ‘Come on, my lads!’ Harry said. ‘We’ll show “em what The Division can do!’ ‘Bellies ain’t filled with fair words,’ somebody growled.

‘Fair words! God damn your eyes, you’ll get no fair words from me, you gin-swizzling, cribbage-faced, cow-hearted Belemranger!’ Harry retorted.

He raised a laugh. The grumbler was elbowed into the background, and informed that he had chosen the wrong officer to try that game on. ‘You silly gudgeon, what do you want to sauce ’im for? ’E’d swear the devil out of ’ell, ’e would! ’E’s a bruising lad, our Brigade-Major. Damned if we hadn’t ought to give ’im a cheer!’

The idea took well; a ragged cheer was raised, which Harry acknowledged by a grin, and a recommendation to the unshaven scarecrows confronting him to save their breath for the march.

Except that the men were hungrier, there was nothing to distinguish the day’s march from the previous one. Along the route, the Light division met stragglers from the main body of the army, slinking off in search of plunder, or dead from exhaustion at the side of the road. It was all very depressing, and although the sight of bleached skeletons of horses was too ordinary to attract any attention, no one much liked to see the stiffening carcases of horses which had failed on the march, and had been dispatched by a merciful musket-shot; or to hear the faint lowing of oxen driving off the road to die miserably in the sodden fields. A little very bad beef, cut from the still-warm bodies of some of the draught-animals, was served out during the usual noon halt. It was rather nasty, and there was no time to cook it properly. A few of the men, kindling fires, toasted slices on the ends of their ramrods, but most of them stuffed the raw chunks into their canteens, where the meat soon turned the little bread they carried with them into a kind of bloody paste. One of Arentschildt’s troopers was seen making his portion into a sandwich, and sharing it with his mount. That made the Englishmen laugh, but there was no denying that the soldiers of the King’s German Legion took much more care of their horses than any British trooper. They would none of them think of eating a morsel before their horses had been fed, and they most of them trained the animals to eat the same food as they ate themselves.

The rumour that the supply-train had gone off by the Ledesma road was confirmed during the halt. That meant there would be no more rations issued until the army reached Rodrigo. The Staff was bitterly cursed, as much by the officers as by the men; quarrels began to break out over trivialities; and even the sunniest-tempered soldiers marched in sulky silence.

The bivouac that night was quite comfortless. It was almost impossible to kindle fires with the green wood, which was all that could be found; and the iron kettles hung over the damply smoking sticks took so long to boil that the men fell uneasily asleep as they waited for them. The French were hovering close in the rear, but they did not show themselves until the following day, when they began to press the rear-guard rather sharply. Through another of the Quartermaster-General’s errors, the cavalry that should have covered the Light division had marched off at dawn, ahead of the infantry, with the inevitable result that the column was a good deal harassed by skirmishing parties of French horsemen. Some of these troops actually penetrated the interval between the Light division and the 7th, and plundered the greatest part of the 7th’s baggage; while a party of three light dragoons had the incredible good fortune to snap up General Paget, just arrived from England as second-in-command of the army. He had been riding, with only his Spanish servant, to hasten the progress of the 7th division, and, being short-sighted as well as one-armed, he had been taken prisoner with almost ridiculous ease. The news raised perhaps the only laugh indulged in by the disgruntled troops that day.

8

The centre column, of which the Light division formed the rear-guard, had orders to encamp on the farther side of the Huebra, but when the rest of the column, jumping down the steep bank into the swollen river, had struggled safely across, a considerable body of French infantry appeared behind the squadrons of dragoons who had been Dickering with the Light division all day. This changed the complexion of things rather seriously, and Harry lost no time in sending Juana forward, with strict orders to stay with the 52nd regiment, who were to move into bivouac while the Riflemen held the bed of the river.

Knowing that Harry would remain with the Riflemen, Juana showed him a white face, pathetically small under the big, dripping hat-brim. Words seemed to be strangled in her throat; she wanted to cling to him, to hold him fast; but of course she knew she must not do that. She managed to say: ‘Take care of yourself!’

He nodded, and patted her check. ‘Of course I will. Cheer up, hija! I’ll be with you presently!’ He wheeled his horse, and rode off in a spatter of mud. Juana found the Padre nervously begging her to make haste, and said grandly: ‘Do not be afraid! We shall be quite safe with the 52nd. How surprised they will be to see me, all our friends in the regiment!’ The Padre seemed to think this remark irrelevant, but the prospect of surprising her friends made Juana feel more cheerful; and she rode on at a smart pace, coming up with the regiment just as it was about to ford the river.

She had the satisfaction of encountering two of Harry’s friends, Major Rowan on the Quartermaster-General’s staff, and Captain Mein; and although neither of them betrayed much surprise at her having joined the regiment, both greeted her with real, if hurried, kindness.

‘Hallo, Juanita! Did Harry send you on?’ Rowan said. ‘That’s right! we’ll take care of you. Stick close to the column, there’s a good girl: wish I could take you under my wing, but you know how it is!’

‘Of course I know, and I don’t want to be under your wing!’ said Juana. ‘Go and attend to your dudes! I have West, and I have also Don Pedro.”

‘What a good duty-officer you’d make, Mrs Smith!’ grinned Rowan. Billy Mein teased her about a splash of mud on her cheek; he asked her, too, sotto voce, where in thunder Harry’s confessor had found his enormous cloak, which made her giggle. But he could not remain with her for more than a few minutes, because he had his company to attend to.

With the French infantry pressing the rear, there was no time to be lost in crossing the Huebra. At this season of the year, it was a wild-looking river, swirling beneath such steep banks that the soldiers, instead of climbing down, jumped into the fast waters. The Padre, watching with a good deal of misgiving, said: ‘But how shall we cross?’ West, always close to his mistress, smiled rather grimly, for he did not much like the Padre. Juana said: ‘I’ll show you!’ and rode Tiny straight for the bank.

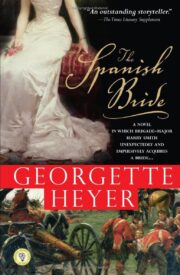

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.