It was a strange place, abominably placed in the dullest kind of country, quite bleak and treeless, menaced by the grand chain of the Guadarrama mountains, which in winter rained down storms from their snowy summits, and in summer cut off from the plain the cooling north-west winds. In all Spain, no greater heat was to be found than that shimmering day-long over the capital. A mean little river watered Madrid; mud walls surrounded it, with, beyond them, fields of tilth stretching away in unbroken monotony to the foot of the sierra. Inside the walls, wealth and poverty lived side by side in startling contrast. Nowhere could be found such broad, clean streets of fine houses, but behind them lurked twisted alleys lined with filthy hovels. Beggars were scarcely ever seen, but in the poorer parts of the town people died like flies of starvation, and night after night emaciated corpses were thrown out of the houses, to be collected and carted away in the morning on hand-barrows. It did not take the army long to discover this shocking state of affairs. The 3rd division started soup-kitchens, and the other divisions quickly followed the example. Pay was months in arrear; no new clothing could be got to replace worn, patched uniforms; officers sold their watches, their silver spoons, and sometimes even their horses; the men lived on their rations; but everyone somehow or other managed to contribute towards alleviating the distress of the city.

But although famine reigned in the background, the festivities planned for the entertainment of the British were on the most lavish scale. No one heard the moaning in the mean streets when the guitars and the mandolines played waltzes and fandangos for British soldiers and their Castilian partners to dance to. The hovels showed blank, dark windows at night, because their inmates had no money to buy as much as a tallow-dip; but on the Puerta del Sol, and the Prado, all down the Galle Mayor, huge wax candles were set out in scores on every balcony, their little tongues of flame burning straight upward in the hot, still air, so brilliantly lighting the town that it seemed like noon at midnight.

The shops displayed the most attractive wares; the cafes set out their little tables on either side of the Prado; guitar-players sang to any party of officers who looked as though they might be good for a peseta or two; the ladies of the town paraded in their best silk petticoats, and smartest satin bodices, flirting their fans, setting the long fringes in their skirts swinging with the provocative play of their hips; lemonade-sellers, in sleeveless waistcoats and white kilts, went up and down, doing a roaring trade under the avenues of trees; the gayest mats were hung out as sunblinds, creating a strange medley of bright hues in streets where the houses were already stained every colour of the rainbow. Two days after his entry into the town, a grand ball was given in Lord Wellington’s honour. Everyone who could beg or steal a ticket attended it. Harry took Juana, dressed in the height of the Spanish fashion, and looking enchantingly pretty, with a high comb in her hair, and a black mantilla draped over it. Kincaid was there, too, in great spirits, because he had sold his baggage-horse, which (he said) ate as much and more than it could carry on its back, and was consequently so thin that he could hang his hat on its hindquarters. But it was a fine, big animal, and he had got a mule and five dollars in exchange for it, so that he was now able, according to Charlie Beckwith, to support a mistress in the first style of affluence. Lord Wellington, always a splendid man for a party, was very affable, not to say jovial. His hawk-eye picked Juana out surprisingly quickly, and he carried her off on his arm to introduce her to several of the most notable people present. ‘My little guerrtire,’ he called her; and nothing would do but he must see her perform a Spanish dance. So one of her countrymen led her on to the floor, while Harry stood by, as proud as a peacock, said his friends. His lordship told Harry, with his loud whoop of a laugh, that he was a lucky young dog. Nothing, in fact, in his lordship’s demeanour would have led even the keenest-eyed observer to suspect that he was preoccupied with matters far removed from balls, and congratulatory addresses. The truth was that his brilliant victory over the Army of Portugal at Salamanca, though it might win for him the thanks of Parliament, the long-postponed appointment as Generalissimo of the Spanish armies, an English marquisate, a Portuguese marquisate, a grant from Parliament, and as much flattery as any man could desire, had waved no magical wand over his most pressing difficulties. His army was so much reduced by sickness that the field hospitals at Salamanca and Ciudad Rodrigo were filled to overflowing, and some of his battalions could muster no more than three hundred bayonets in line; the war-chest was so diminished that he could neither pay the hale troops, nor support the sick men in the rear; two of his most competent generals, Graham and Picton, had been invalided; Beresford, Cotton, Leith, and Cole, all wounded at Salamanca, were in hospital; the Spanish officials with whom he was obliged to deal seemed to have been chosen for their inefficiency (‘an impediment to all business,’ he called one of them); he had had to leave Clinton’s division to contain what remained of Marmont’s army on the Douro; and he was quite uncertain of what Soult’s movements in Andalusia would be. But no trace of these cares was allowed to appear in his lordship’s public manner; indeed, very few people knew that such cares existed. To most of the light-hearted gentry making merry at the ball, the Allied army’s prospects seemed to be rosier than ever before. They had shattered Marmont’s force (‘Forty thousand men beaten in forty minutes,’ someone said); Marmont himself, at first reported slain, was badly wounded; two of his Generals had been killed; the French losses were anything from ten to fifteen thousand men, two Eagles, and twenty guns; and here was the Allied army, actually quartered in King Joseph’s capital! Never had there been more excuse for dancing!

3

There was every facility for dancing. Those who could not obtain tickets for the state balls could go any night of the week to the Principe, and enjoy themselves at the public balls held there. Nor was dancing all that Madrid had to offer its visitors. There were theatres; and concerts; plenty of sport to be had in the Grand Park, which abounded with game; public executions in the Plaza Mayor, if you had a fancy to witness a garrotting; and bull-fights in the Plaza de los Toros, shut for years, but opened again in honour of the British army. Business in Madrid on a bull-day was at a standstill. From ten o’clock in the morning onwards, crowds besieged the gates of the bull-ring, struggling and fighting for the best places, and apparently quite content, having won them, to sit for hours in all the heat and glare of the August sunshine, waiting for the show to begin, with nothing to do but to drink lemonade, and eat sticky sweetmeats fast melting into glutinous masses on the vendors’ trays.

The English liked some part of the bull-fights, but very few cared to see the slaughter of broken-down horses which formed an apparently essential feature of the spectacle; and all of them were agreed that it was no sight for women. Harry would not take Juana, which made her cross, until she heard that Kincaid had seen his erstwhile baggage-horse driven into the ring, and then she was glad, and quarrelled with Kincaid for laughing about it. The garrison of the Retiro surrendered within a few days, and Lord Wellington, having given a superlatively grand ball at the end of August, left Madrid, with the 1st, 5th, and 7th divisions, some Portuguese troops, and two brigades of heavy cavalry, to reinforce Clinton. He left the 4th division at Escurial, and the 3rd and Light divisions in and around Madrid. He had learned, late in the month, that Soult had at last begun to evacuate Andalusia, raising the siege of Cadiz, which had been dragging on for a little matter of three years. General Hill, commanding the containing force in Estremadura, wrote that Drouet’s troops in his front had vanished, presumably having marched off to join Soult, who was concentrating at Granada. Since King Joseph, with the Army of the Centre, and the most immense train of baggage and refugees ever seen, was marching slowly eastward to Valencia, to effect a junction with Suchet, there could be no possibility of Soult’s continuing to maintain himself in Andalusia. He, too, would in all probability march eastward. That would take him many weeks, and a warm welcome he would receive from King Joseph (if ever he got into touch with that much-harassed monarch), for he had been behaving in the most intransigent fashion, quarrelling with him in dispatch after dispatch, giving him quite erroneous information, and even refusing to obey his positive orders.

Lord Wellington, deciding that no immediate danger threatened Madrid, left the city on the last day of the month, instructing Hill, as soon as he could be assured of Soult’s departure for the east, to march on the capital, and to take over the command of the troops left there. When he should have settled accounts with the French Army of Portugal, which was lifting up its head again, under Clausel, his lordship meant to return to Madrid, to confront the combined forces of Joseph, Suchet, and Soult.

Meanwhile, the divisions left at Madrid continued to amuse themselves as well as they were able. Lack of money was, as always, the chief bar to enjoyment, but there were ways, if one was an old campaigner, of getting over this difficulty. One enterprising gentleman, instead of indulging in a little honest plunder, or some legitimate pilfering, took under his protection a singularly ill-favoured widow who owned, in addition to a large wart on her nose, quite a tidy little nest-egg. But such shifts as these were not much approved of in the ranks. ‘You’d marry a midden for muck, you would!’ a frank-spoken friend told the complacent bridegroom. The officers, most of them deep in the toils of moneylenders, contrived to go on indulging in all the usual amusements offered by a capital city. The Smiths, neither being handicapped by an imperfect knowledge of the language, made a number of friends, and began to lead, Harry said, quite a respectable and domestic existence.

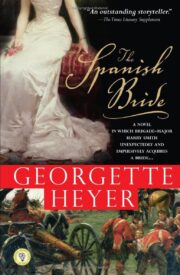

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.