The storm of the previous evening had given place to a brilliant day, with a cloudless sky, and a hot sun swiftly drying the ground which had been so drenched a few hours before. The men lay by their arms, grumbling and smoking, and trying to protect themselves from the glare by such means as came most readily to hand. Except for some changes in’ the disposition of the divisions, the morning was spent in almost complete inaction. Outposts and vedettes reported the French to be similarly undecided, which was felt to be some comfort; but at noon, when it was rumoured that a plan of retreat was being drafted, feelings began to run high.

Harry, who, as Brigade-Major, was in a position to know rather more about the movements of the various divisions than his friends, saw no reason to banish his wife to the rear until after two in the afternoon. Except that Pakenham, in command of Picton’s division, had been ordered up from the north side of the Tonnes to a position in the right rear of the front, near the Ciudad Rodrigo road, no movement of any importance had taken place. Lord Wellington, who with his Staff, Marshal Beresford, and the Spanish Commissar, General Alava, had established his headquarters in a farmhouse, somewhere towards the right of the line, was reported at two o’clock, by one of his aides-de-camp, to be sitting down to a belated lunch of hunks of cold meat clapped between slices of bread. It was at this moment that Marshal Marmont began to extend his left.

Maucune’s division was the first to move. Just before two o’clock, it was observed to march towards the centre of the narrow plateau, which extended for three miles to the west of the French position. A smooth slope to the north led up to the Allied line, but since this was cleverly masked, the French had no very exact knowledge of either its formation or its strength. They marched to the centre of the plateau, until the road leading from Salamanca to Alba de Tonnes was reached, and here, before the village of Arapiles, which was held by Leith’s division, they halted, and began to deploy. Their voltigeurs were sent out to work down the slope to the village, and the thunder of artillery-fire broke out. Someone, returning from headquarters, said that a Staff-officer had ridden off to the farm, where Wellington sat in the yard, eating his lunch at a deal table, and had announced that the French were extending. ‘The devil they are!” had said his lordship, stuffing the rest of his sandwich into his mouth, and striding off to a place of vantage. ‘Give me the glass quickly!’ Lord Fitzroy Somerset handed it to him, and for a few moments his lordship observed the French movement in silence. Presently he lowered the glass, and said in a brisk tone: ‘Come! I think this will do at last!’

‘Did he?’ Harry cried. ‘By Jupiter, then we’re going to fight!’

‘Yes, and that Spanish fellow-what’s-his-name?-Alava!-kept on saying: “Mais que fait-il? Que fait Marmont la-bas?” and old Hookey gave one of his laughs, and said (for I heard him) “Mon cher Alava, Marmont est perdu!”

‘Oh, famous!’ Harry said. ‘But I must get my wife out of this at once.’

But West had already taken Juana to the rear, telling her woodenly that Master’s orders had been explicit. She was in a rage with him, because she wanted to stay with the brigade, and watch her first battle, and she thought that if Harry were wounded he would like to have his wife at hand to attend to him. West said, No, it was the last thing Master would like, a statement which made Juana so cross that she sulked all the way to Las Torres, a village situated about a mile behind the Allied right. However, the reserve was stationed at Las Torres: a force consisting of a Portuguese brigade, Espana’s Spanish contingent, and Anson’s, Le Marchant’s, and Arentschildt’s cavalry, and the throng of troopers with their sleek mounts made Juana feel much more cheerful. She liked the warm smell of horseflesh, the jingle of accoutrements, and the splendour of scarlet uniforms, glittering helmets, and swirling plumes, and she very soon stopped sulking, and began to look about her in the hope of perceiving an acquaintance. In the crowd of horses and lounging troopers it was hardly surprising that she did not recognize anyone, but upon entering Las Torres she had the excitement of seeing Lord Wellington himself ride past at a full gallop. There was no mistaking that low-cocked hat, and bony profile, but to see his lordship going hell-for-leather, and unattended, was something quite out of the ordinary way. His Staff rode past in pursuit of him a few moments later, going hard, but clean outpaced. Juana, who had dismounted in the village, and found herself standing beside an officer of the 3rd dragoons, asked him in the friendliest fashion if he knew where his lordship was bound for. He said, in halting Spanish, that he had no certain knowledge, but supposed he must be going to order Pakenham up.

It was not until much later that they heard how Wellington had ridden up to his brother-in-law, not entrusting to anyone the order he had for him.

‘Edward,’ had said his lordship in his cool, imperative way, ‘move on with the 3rd, take the heights in your front, and drive everything before you!’

It soon became known, of course, that the 3rd was moving up to the front, but as the division had two miles of rough ground to cross, it was a long time before anything more was heard of its doings. The artillery-fire continued; scraps of news filtered through to the rear; and her new acquaintance in the 3rd dragoons was able presently to assure Juana that the Light division was not engaged, being placed on the extreme left of the line, containing Foy’s and Ferey’s divisions in their front.

These tidings were clearly excellent, and Juana, her mind relieved of its chief anxiety, began to enjoy herself. Her henchwoman had gone off with the baggages-train, but West remained in close attendance on her, so that she did not miss rough Jenny at all, but, on the contrary, was rather glad that she had only one person to watch over her.

After a time, a number of wounded began to trickle towards the rear, but from what they said it did not seem as though the two armies had as yet come to grips. They were all suffering from gunshot wounds, and the only news seemed to be that the French army was still extending along the plateau, Thomieres’ division having followed Maucune’s, and the whole force now presenting a dangerously elongated appearance. Nobody knew quite what was happening, though it was obvious that Marmont’s object was to cut Wellington off from Ciudad Rodrigo. Maucune’s division was still before the village of Arapiles, and there was some hand-to-hand fighting going on, but only between advance-guards. Thomieres, one officer with a grape-shot wound in his chest said, had passed Maucune, and was forging westward along the plateau, leaving a very unsoldierly gap between the two divisions. In fact, the opinion held by most of the men who had been in a position to observe the French movement, was that it was a slovenly manoeuvre, such as would never have been initiated by the English commander.

8

Juana, who had taken up temporary quarters in a posada in the centre of the village, was joined there presently by a lady who came into the yard with a soldier-servant, and desired the landlord to bring her a glass of lemonade. After looking at Juana for a few moments, she went over to her, and asked if she too had a husband in the army. She was a good many years older than Juana, an Englishwoman with a deeply tanned and weather-beaten skin, and careworn lines at the corners of her eyes.

West, who had just come out of the shed where he had tethered the horses, touched his hat, and explained that his mistress spoke no English. The lady repeated her question in Spanish, and when Juana answered, Yes, she was married to an English officer, she said wonderingly: ‘I had not thought it possible! You are so young, my dear.’ ‘Oh no!’ Juana assured her. ‘I shall very soon be fifteen. I have been married since three months already.’

The lady smiled. ‘My dear! And your husband? What is his regiment?’ ‘He is a Rifleman,’ said Juana. ‘Also he is a Brigade-Major, which is a position of great responsibility, you understand.’

‘Indeed, yes,’ agreed the lady, a twinkle in her eyes. ‘Do you know, I think I have heard of you? Were you not married after Badajos?’

‘Yes, I am Mrs Harry Smith,’ said Juana. ‘And you, señora?’

‘I am Mrs Dalbiac. My husband is Colonel of the 4th dragoons. These are very anxious times for us poor wives, are they not?’

‘Yes, but also they are very exciting,’ Juana pointed out.

‘Ah, when you have followed the army for as long as I have, you will not care for the excitement!’ sighed Mrs Dalbiac.

Juana did not think this was very probable, but being too polite to say so, she asked Mrs Dalbiac instead if she would like to see her horse, Tiny. Mrs Dalbiac seemed to think that Tiny was rather a mettlesome mount for a lady, but Juana explained how stupid the Portuguese horse had been in crossing the river, and how frightened he was of the storm, and Mrs Dalbiac said, but with that look of wonder in her eye, that certainly nothing could be worse than a cowardly horse. She asked Juana questions about her family, and seemed greatly moved by Juana’s graphic account of the circumstances leading up to her marriage. She shuddered at the description of the sack of Badajos, and evidently pitied Juana very much for being an orphan, and having lost all means of getting into touch with her sister. Juana, although she was not above drawing, in moments of stress, the most heartrending picture of her orphaned condition, for Harry’s benefit, was not really in the least concerned with her sister’s disappearance from her life, and found this conversation rather tedious. However, Mrs Dalbiac, having drunk her lemonade, went away presently to rejoin her husband, promising to return in a little while.

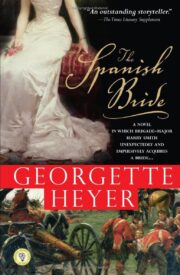

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.