At the end of the long day’s march, when the columns, reinforced since Torrecilla de la Orden by the 5th division, drew near to the Guarena river, the pace of both armies quickened. The firing almost ceased as the dog-weary troops strove to be the first to reach the river. The Light division began to gain on the French column, and even the candidate for a cavalry regiment forgot his grievances in a determination to gain the rising ground beyond the river before the enemy could occupy it. ‘By Gob, we’ll do it!’ he said, rather breathless, but happy for the first time that day. ‘Regular Talavera march, this ’ere!’ ‘Christ, I’m dry!’ croaked a recruit, passing the tip of a swelling tongue between his cracked lips.

But although every man amongst them was parched with thirst, the Light division did not halt by the river, but drank as they marched through the shallow ford, scooping up the tepid, muddied water in their hands or their shakos. Some of the recruits were inclined to grumble at the inhumanity of officers who would not permit them a few minutes’ respite, but they got no sympathy from the veterans. ‘You stop here swilling your guts, and you’ll be put to bed with a shovel!’ said a Rifleman grimly.

The truth of this pronouncement was demonstrated a little later, when the 5th division, reaching the stream, halted there. The French guns, hurried into position on the hills above, at once opened fire, providing the Johnny Raws, said Tom Crawley, watching the flurry and carnage in the river, with an excellent object lesson. ‘That’ll learn the Pioneers,’ he remarked dispassionately. ‘If you start in to take liberties with them Frogs, my lad, you’ll find yourself in a peck of trouble, and don’t you forget it!’

Lord Wellington was not allowed to occupy his ground quite without opposition, but after a somewhat costly attempt to dislodge him, Marmont called in his skirmishing parties, and allowed his exhausted troops, who had covered a distance of eighty miles in two days, to bivouac for the night. ‘And if anyone can tell me what the devil all this manoeuvring has been about, I shall be grateful!’ said Eeles.

‘Marmont’s too clever by half,’ said Charles Beckwith, who was feeding a camp-fire with bundles of stubble. ‘He gained a day’s march on us when he crossed the Douro, too, not to mention turning our whole position. He could have got to Salamanca, if he hadn’t been so anxious to show us how prettily he can manoeuvre.’

‘Damn his eyes!’ said Eeles, tenderly inspecting his afflicted heel. ‘Well, he’s gained nothing by it but the devil of a lot of casualties,’ said Beckwith. ‘Yes, he has,’ said Harry, grinning. ‘He’s gained George’s canteen!’

Beckwith looked up. ‘Oh no, has he really? Careless fellow, George! Always dropping your things about!’

‘It’s all very well for you to start funning,’ said Simmons, receiving this baseless accusation with his usual good-humour. ‘It’s no joke for me, though, for I’ve lost my mule as well. A fine young mule, too. He got a kick from a stallion on the march, and my fellow had to cut him loose. Broken thigh-bone. The worst is, I had a variety of comforts packed up with my canteen, which I shan’t easily be able to replace. It’s a sad grievance, I can tell you.’ ‘Never mind, George, you shall have supper with us,’ Harry said. ‘We’ve got a chicken.’ Eeles, who had been smearing tallow on his heel, rolled over on to his elbow, and called out: ‘Juana! Oh, Juana! Mrs Smith! Queridissima amiga! Will you invite me to supper with you?’ Juana came out of Harry’s tent, and walked over to the fire. ‘Que fastidio! No, because there will not be enough food.’

‘Where did you manage to pick up a fowl, Juana? Beckwith asked, folding his greatcoat to make a seat for her.

‘Joe Kitchen stole it,’ she replied.

Harry laughed, holding her in the crook of his arm. ‘I’ll swear you told him to!’ ‘Well, I thought we should need it,’ she explained, leaning gratefully against his shoulder. ‘Tired, hija?’ he said.

‘Muy causada,’ she admitted, sleepily smiling. ‘When must we march again?’ ‘That’s easily answered,’ said Eeles. ‘At dawn, just when you’re dropping into your second sleep.’

‘Señor Kincaid,’ remarked Juana inconsequently, ‘says that dawn is when one can see a grey horse a mile away.’

‘Well, let’s hope to God there isn’t any cavalry in our front,’ said Eeles.

6

When the dawn came, however, all was quiet in the French lines. The sky was overcast, and a hot wind blew steadily. Particles of dust seemed to penetrate even into the most tightly closed receptacles. Jack Molloy swore that there was some even in the egg his batman boiled for his breakfast In spite of the heat, the fatigue of the previous day, and the depressing effect of finding friends missing from the ranks, the spirits of the men were good. Not many of them understood the purpose of their gruelling march, but they could all see that they were facing the French, and placed in a strong position which they could defend all day, if need be.

‘They won’t attack us!’ said an old hand. ‘They’re eating their breakfasts, that’s what they’re doing. Bacon and eggs, and hunks of beef, what they plundered off the poor, blurry Spaniards. What we ought to ’av ’ad, if we wasn’t bleeding little gentlemen.’ ‘That’s right,’ agreed a disreputable individual, who was frying slices of pork on the end of his priming-rod. ‘Cruel it is, the way them Johnny Petits plunder the country. All they left for us was one scrawny porker. Where’s the Commissary?’ ‘Lorst, as usual.’

‘Well, damme, boys, if he don’t show his front, we must either find a potato-field, or ’ave a killing-day!’ said a stout Rifleman cheerfully.

As the morning wore on, without any other sign of activity in the French lines than the movement of various reconnoitring parties, it became apparent that Marshal Marmont, having neatly turned Wellington’s flank on the 16th July, and during the two succeeding days, superbly manoeuvred the French army over eighty miles of sunburnt country, had decided to give his stoical infantry a rest. The entire army remained stationary all day, and moved off in the cool of the evening, in a southerly direction.

‘Oh, damn it! I believe they’re as chary of coming to grips as we are!’ said Young Varmint despairingly. ‘All this watching and prowling reminds me of nothing so much as the start of a cat-fight!’

It really began to seem as though the caution of the opposing Generals would result in nothing but a stalemate, for the weary marches continued for two more days, in much the same fashion, the armies sometimes within half-musket shot of each other, sometimes out of sight, but never engaging in any more serious hostilities than artillery-fire, and some cavalry skirmishing. Once, when the rival columns were seen to be converging on the same village, a general engagement seemed to be inevitable, but Wellington, to the wrath of the major part of his army, refused battle by avoiding the village.

By the time the Allied army reached the Tonnes, a number of sick and wounded men were missing from the ranks, and the baggage-train, shepherded by a Portuguese brigade of cavalry, had begun to straggle. Nothing had been seen of the French for some hours, but when the camp-fires were presently lit, it was observed that some of the French divisions were bivouacking within striking distance of the fords of Huerta.

Early on the following morning, Wellington withdrew his army to its old position on the heights of San Christoval, above the more northerly fords of Aldea Lengua, and Santa Marta.

‘In fact,” Eeles said, ‘we might as well have stayed here the whole time, and never have gone to Rueda at all. Then I shouldn’t have had the worst blister in the army.’ As Lord Wellington seemed to have decided to allow Marshal Marmont to pass the Tonnes unopposed, Charles Eeles was able to nurse his heel all day. The Allied army remained in position on the heights until sundown, while the French troops slowly crossed the river by the fords of Huerta, marched up the valley on the farther side, and encamped at the edge of a forest barely six miles from Salamanca.

Juana seized the opportunity to wash and iron two of Harry’s shirts. He found her propping her iron up on a stubble-fire, which she had ordered Joe Kitchen to build for her. She looked hot, with her dark ringlets clinging damply to her forehead, and beads of sweat on the bridge of her nose. Harry took the iron away from her, and gave it to Kitchen. ‘No, my little love,’ he said, leading her away. ‘Not so!’

‘But Kitchen does not iron at all well, amigo! I assure you-’ ‘And I assure you I won’t have it. I gave you orders to rest, you little varmint!’ ‘Indeed, I am not tired! De ningun modo!’

‘Tanto mejor!’ He drew her into the shade of a tree, and sat down on the ground, pulling her down beside him. He was looking tired, finer-drawn than he had been at the start of the campaign, with the lines running from his nose to the corners of his mouth deeper-cut, giving his thin face a sterner expression.

Juana said: ‘En efecto, it is you who are tired, mi Enrique!’

‘Very. It’s these cursed boils.’ He stretched himself out on the ground, with his head pillowed in her lap. ‘Comfort your boy,’ he murmured, his eyes smiling up at her under their weighted lids.

She let her fingers stray over his hair. They trembled a little; a rush of tenderness welled up in her. She stammered: ‘Do you think I am a bad wife?’

‘I don’t know. I never had another.’ ‘I tease you with my bad temper!’

‘Si!’ Harry’s eyelids were dropping. ‘I meant to be so good!’ she said distressfully. His eyes opened again. ‘What’s all this?’ ‘I am afraid you will be killed in the battle.’ ‘Juana, you goose!’

She bent over him, gently pressing her hands against his hollow cheeks. ‘I have only you. If you die, I must also. Do you see?’

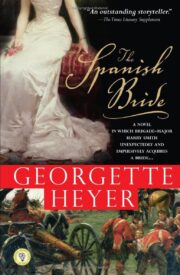

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.