Hell. It would have been much easier to deal with getting a new cloak.

This was ridiculous! He didn’t know whether to defend himself—the Purple Gentian bit of himself, that was—or to be jealous of his Purple Gentian self on behalf of his himself self. Devil take it, even his thoughts were in a deuced tangle. There was one way to end all the tangles and confusion.

Richard’s mouth opened but no sound came out. He’d thought he would feel better when he told Deirdre, hadn’t he? And look what had come of that. Who would the casualty be this time? Geoff? Miles?

Richard’s mouth shut into a very tight line.

Amy was watching him closely. “Were you about to say something?”

Richard shrugged. “Merely that your secret love, whoever he may be, is a very lucky man. Shall we return to the others?”

The walk back across the garden was considerably quicker than the stroll out; Amy had to scurry to keep up with Richard’s brisk strides. Maybe it had to do with being out of breath, but victory didn’t leave nearly as sweet a taste in Amy’s mouth as she had anticipated. Could one really use the term victory, when Lord Richard hadn’t so much as glanced at her since they had started back down the path?

If he had ever really cared, he would never have given up that easily. Clearly, thought Amy savagely, she hadn’t even been an infatuation. She had been nothing more than a dalliance.

Henrietta looked up eagerly as Richard and Amy hove into view. “Did you have a nice . . .” she began brightly, but the phrase trailed off as she caught sight of her brother’s stony face.

“I’ll leave you here to get acquainted.” Richard all but shook Amy’s fingers off his arm, executed a bow in her general direction, and plunged through the French doors into the drawing room.

“Richard! Pssst!” His mother’s arm shot out and dragged him behind a faux mummy case. “Over here!”

“Ouch.” Richard rubbed his wrist and glowered down at his mother. When in matchmaking mode, somehow his diminutive parent’s strength was as the strength of ten. Ten pugilists, that was.

“Sorry, darling,” the marchioness absentmindedly patted her son’s wrist, but her solicitude was short-lived. “What happened? You were outside with her for ages!”

Richard gave evasion a try. “Is Miles flirting with Hen?”

Lady Uppington rolled her eyes. “If Miles is flirting with Hen, I’m sure Hen is happily flirting back. Besides, they’re perfectly well chaperoned by that nice Miss Meadows. Do stop trying to change the subject, Richard. I don’t know why you children always think you can distract me like that.”

“When have we ever tried to distract you, Mother? You’re far too sharp for us.”

Lady Uppington narrowed her eyes. “Let’s see. . . . There was the time you and Charles . . . Oh no. I’m not falling for that old dodge. Come now, darling, won’t you talk about it to your”—Lady Uppington patted the side of the mummy case—“mummy?”

Richard groaned. “That was beyond awful, Mother.”

“Some children have no gratitude. What happened, darling?”

“Amy thinks she’s in love with the Purple Gentian.”

“But you are—”

“I know!”

It was at that highly edifying moment that Miles chose to pop behind the mummy case. The marchioness looked miffed.

“Why so gloomy? Is it . . . the mummy?”

Richard glowered at his best friend. “Don’t you start.”

“I promise to behave as long as you provide refuge from the hen party—and I do mean, a Hen party—on the balcony. They’ve all got their heads together, and when I wandered over, Hen flapped her hand at me and told me I was superfluous. I’m not sure which was more provoking, the sentiment or her vocabulary.”

Miles heaved a disgruntled sigh. Lady Uppington beamed with maternal pride. Richard noticed none of this; his head was craning around the edge of the mummy case, peering at the little grouping beyond the French doors. It was, terrifyingly, just as Miles had described: Jane’s fair head, Henrietta’s glossy chestnut, and Amy’s bouncy curls all bent close together. A steady sibilant sound drifted through the air. Richard didn’t want to know what they were talking about. Which meant, of course, that he rather desperately wanted to know whether they were talking about him.

Richard strained to listen, his fingers grasping the side of the mummy case. “No!” Henrietta exclaimed, bouncing on her bench. “You can’t be serious!” The heads swooped back together. Hiss, hiss, hiss . . .

Had Richard known what was being said on the balcony, he would have been even more alarmed.

“What do you mean he didn’t tell you who he was? That’s appalling!”

Within ten minutes, by means of ambiguous half-statements and strategically raised eyebrows, Amy had managed to ascertain that Henrietta knew of Richard’s dual identity. Once that was out of the way, the conversation became much more direct.

“How could he let you think he was two people?” Henrietta glowered in the direction of her brother. “That’s . . .” Having already used appalling, she cast about for another term. “Unconscionable!” she finished triumphantly.

“I feel an idiot for not having realized. If I hadn’t been so convinced that he was utterly under Bonaparte’s thumb . . .”

“It is a wonderful disguise, isn’t it?” Henrietta belatedly remembered that they were excoriating Richard, not praising him. “But he still should have told you.”

“What hurts the most is that he didn’t trust me enough to tell me,” Amy confided. “Just now, when I told him I loved another, he could have made amends by simply saying . . .”

“ ‘By the way, that other happens to be me? Sorry, forgot to tell you before?’ ” Henrietta supplied.

Amy grinned despite herself. “Something like that.”

“Oh no. That would have been far too easy. He’s an absolute dear, and a wonderful brother, but he is a boy.” Henrietta shook her head in irritation. “He has delusions of authority. They all do. He thinks he always knows what’s best for everyone and how to organize their lives.”

“That’s exactly the problem!” Amy waved her hands about excitedly. “He needs to be shown that he can’t always organize everything for everyone.”

Henrietta looked gratified. “Oh, absolutely!”

“Something must be done.”

“I couldn’t agree more.” Henrietta nodded emphatically. “They need to be taken down a peg or two occasionally. For the good of womankind.”

“Amy, are you going to?” Jane put in.

“Do you have a plan already? Oh, please tell!” Henrietta swished her long hair out of her face, and leaned forward imploringly. “I won’t utter a word.”

“We do have a plan,” Amy uttered thrillingly.

Henrietta listened, enthralled. “Smashing!” she exclaimed, when Amy and Jane had finished filling in the details. “The Pink Carnation! I love it! Especially the name.” She giggled. “How may I help?”

“Shhh!” Jane hissed abruptly. “He’s coming!”

All three girls instantly sat up straight and folded their hands in their laps.

Richard glowered suspiciously at his sister as he stepped out onto the balcony. Henrietta smiled at him with an innocence that informed him instantly that his worst fears were correct.

Richard kissed his sister on the cheek, and bowed over Jane’s hand.

He didn’t bow over Amy’s hand. He didn’t nod. He simply looked at her. Only there was nothing at all simple about the way he was looking at her.

His eyes burned into hers with a mixture of longing and pain that held Amy transfixed. Returning the stare, pain for pain, longing for longing, Amy fought the urge to grab his hand. Even had she not had her pride to consider, a hand would have been redundant. Their eyes locked them closer than any handclasp, closer than speech.

Richard broke the gaze first.

With a toneless “Good night, Miss Balcourt,” he turned on his heel and left the balcony. His unyielding back strode out the French doors, through the salon, and disappeared from sight.

Richard’s sister slid her arm through Amy’s and squeezed. “Courage,” Henrietta cheered her. “Remember the good of womankind.”

“Right,” Amy muttered, eyes still on the door through which Richard had exited a moment before. “The good of womankind.”

She could be heard muttering the phrase through her teeth at intervals for the rest of the evening.

Chapter Thirty-Three

In a dark house in a dark street in the predawn blackness of the Ile de la Cité, a single candle burned. The grudging light of the candle illuminated a chamber as meager as the single flame itself. A narrow bed, unwelcoming and unslept in, stood against one wall, flanked by a barren nightstand. A pair of ancient leather slippers lay at uneven angles on the scarred wooden floor. In a straight-backed chair by the room’s sole window sat Gaston Delaroche.

At half past two the signal came, the sound of an owl hooting in the alleyway behind the window. The Assistant Minister of Police raised the sash of the window, and a slight, dark figure joined the shadows under the crooked overhang of the second story of the old house. If words were whispered, the sound was submerged under the million nighttime noises of the crowded street. The abrupt snuffle and hiss of snoring men, the creak of rope beds, and the rustle of feather ticks created a monotonous hum. From the upper reaches of Delaroche’s boardinghouse came the sharply muffled cry of a small child, and a man’s irritated grumble. The sash of Delaroche’s window slid silently closed. The shadows were once again merely shadows.

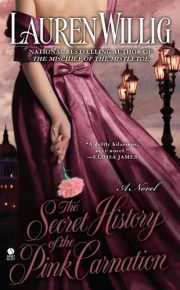

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.