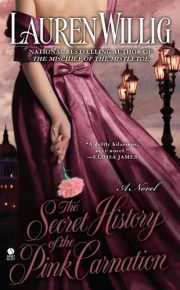

Lauren Willig

The Secret History of the Pink Carnation

To my parents

Acknowledgments

Like first-time Oscar winners, who thank everyone from their first-grade teacher to that great chiropractor they saw last month, and have to be hauled offstage by the scruff of their tuxes, I have many, many people to whom I owe most humble thanks for the existence of this book. Unlike those Oscar winners, there’s no orchestra waiting to strike up if I babble too long. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

And the acknowledgments go to . . .

Brooke, little sister and favorite heroine-in-training, for providing plot ideas, giggling over the giggly bits, and nobly refraining from bludgeoning me every time I squealed, “Ooh! Come see this bit of dialogue I just wrote!” The next book is yours, Brookie-fly!

Nancy Flynn, most kindred spirit ever, for scads of publishing advice, even more scads of moral support, and for giving the Purple Gentian his name.

Abby Vietor, for playing fairy godmother to the Pink Carnation all the way, from reading early chapters to whisking the finished manuscript off to Joe (see under Agent, Super)—this book wouldn’t be here without you.

Claudia Brittenham, for knowing my characters better than I do, care packages of candied violets, and retrieving my sense of humor when I misplace it.

Eric Friedman, for listening to three years of babble about the Purple Gentian—even if he did want to call it The Rogue Less Traveled.

The wonderful women of the Harvard history department, Jenny Davis, Liz Mellyn, Rebecca Goetz, and Sara Byala, for always being there with a coffee or a cosmo.

Joe Veltre, aka Super Agent, for taking a mix of sheep jokes, French bashing, and the occasional heaving bosom and molding it into a book.

Laurie Chittenden, my fabulous editor, for shooing away the sheep, and keeping the manuscript from bloating to War and Peace proportions.

Finally, the brilliant ladies of the Beau Monde and Writing Regency, for knowing about everything from Napoleon’s politics to the cut of Beau Brummel’s waistcoat, and sharing it all with me despite my lapse into the modern.

Thank you all!

Prologue

The Tube had broken down. Again.

I clutched the overhead rail by dint of standing on the tippiest bit of my tippy toes. My nose banged into the arm of the man next to me. A Frenchman, judging from the black turtleneck and the fact that his armpit was a deodorant-free zone. Murmuring apologies in my best faux English accent, I tried to squirm out from under his arm, tripped over a protruding umbrella, and stumbled into the denim-covered lap of the man sitting in front of me.

“Cheers,” he said with a wink, as I wiggled my way off his leg.

Ah, “cheers,” that wonderful multipurpose English term for anything from “hello” to “thank you” to “nice ass you have there.” Bright red (a shade that doesn’t do much for my auburn hair), I peered about for a place to hide. But the Tube was packed solid, full of tired, cranky Londoners on their way home from work. There wasn’t enough room for a reasonably emaciated snake to slither its way through the crowd, much less a healthy American girl who had eaten one too many portions of fish and chips over the past two months.

Um, make that about fifty too many portions of fish and chips. Living in a basement flat with a kitchen the size of a peapod doesn’t inspire culinary exertions.

Resuming my spot next to the smirking Frenchman, I wondered, for the five-hundredth time, what had ever possessed me to come to London.

Sitting in my carrel in Harvard’s Widener Library, peering out of my little scrap of window at the undergrads scuttling back and forth beneath the underpass, bowed double under their backpacks like so many worker ants, applying for a fellowship to spend the year researching at the British Library seemed like a brilliant idea. No more student papers to grade! No more hours of peering at microfilm! No more Grant.

Grant.

My mind lightly touched the name, then shied away again. Grant. The other reason I was playing sardines on the Tube in London, rather than happily spooling through microfilm in the basement of Widener.

I ended it with him. Well, mostly. Finding him in the cloakroom of the Faculty Club at the history department Christmas party in a passionate embrace with a giggly art historian fresh out of undergrad did have something to do with it, so I couldn’t claim he was entirely without a part in the breakup. But I was the one who tugged the ring off my finger and flung it across the room at him in time-honored, pissed-off female fashion.

Just in case anyone was wondering, it wasn’t an engagement ring.

The Tube lurched back to life, eliciting a ragged cheer from the other passengers. I was too busy trying not to fall back into the lap of the man sitting in front of me. To land in someone’s lap once is carelessness; to do so twice might be considered an invitation.

Right now, the only men I was interested in were long-dead ones.

The Scarlet Pimpernel, the Purple Gentian, the Pink Carnation . . . The very music of their names invoked a forgotten era, an era of men in knee breeches and frock coats who dueled with witty barbs sharper than the points of their swords. An era when men could be heroes.

The Scarlet Pimpernel, rescuing countless men from the guillotine; the Purple Gentian, driving the French Ministry of Police mad with his escapades, and foiling at least two attempts to assassinate King George III; and the Pink Carnation . . . I don’t think there was a single newspaper in London between 1803 and 1814 that didn’t carry at least one mention of the Pink Carnation, the most elusive spy of them all.

The other two, the Scarlet Pimpernel and the Purple Gentian, had each, in their turn, been unmasked by the French as Sir Percy Blakeney and Lord Richard Selwick. They had retired to their estates in England to raise precocious children and tell long stories of their days in France over their postdinner port. But the Pink Carnation had never been caught.

At least not yet.

That was what I planned to do—to hunt the elusive Pink Carnation through the archives of England, to track down any sliver of long-dead gossip that might lead me to what the finest minds in the French government had failed to discover.

Of course, that wasn’t how I phrased it when I suggested the idea to my dissertation advisor.

I made scholarly noises about filling a gap in the historiography, and the deep sociological significance of spying as a means of asserting manhood, and other silly ideas couched in intellectual unintelligibility. I called it “Aristocratic Espionage during the Wars with France: 1789–1815.”

Rather a dry title, but somehow I doubt “Why I Love Men in Black Masks” would have made it past my dissertation committee.

It all seemed perfectly simple back in Cambridge. There must have been some sort of contact between the three aristocrats who had donned black masks in order to outwit the French; the world of the upper class in early nineteenth-century England was a small one, and I couldn’t imagine that men who had all spied in France wouldn’t share their expertise with one another. I knew the identities of Sir Percy Blakeney and Lord Richard Selwick—in fact, there was a sizable correspondence between those two men. Surely, there would be something in their papers, some slip of the pen that would lead me to the Pink Carnation.

But there was nothing in the archives. Nothing. So far, I’d read twenty years’ worth of Blakeney estate accounts and Selwick laundry lists. I’d even trekked out to the sprawling Public Record Office in Kew, hauling myself and my laptop through the locker rooms and bag searches to get to the early nineteenth-century records of the War Office. I should have remembered that they call it the secret service for a reason. Nothing, nothing, nothing. Not even a cryptic reference to “our flowery friend” in an official report.

Getting panicky, because I didn’t really want to have to write about espionage as an allegory for manhood, I resorted to my plan of last resort. I sat on the floor of Waterstones, with a copy of Debrett’s Peerage open in my lap, and wrote letters to all the surviving descendants of Sir Percy Blakeney and Lord Richard Selwick. I didn’t even care if they had access to the family archives (that was how desperate I was getting), I’d settle for family stories, half-remembered tales Grandpapa used to tell about that crazy ancestor who was a spy in the 1800s, anything that might give me some sort of lead as to where to look next.

I sent out twenty letters. I received three responses.

The proprietors of the Blakeney estate sent me an impersonal form letter listing the days the estate was open to the public; they helpfully included the fall 2003 schedule for Scarlet Pimpernel reenactments. I could think of few things more depressing than watching overeager tourists prancing around in black capes, twirling quizzing glasses, and exclaiming, “Sink me!”

The current owner of Selwick Hall was even more discouraging. He sent a letter typed on crested stationery designed to intimidate, informing me that Selwick Hall was still a private home, it was not open to the public in any capacity, and any papers the family intended for the public to view were in the British Library. Although Mr. Colin Selwick did not specifically say “sod off,” it was heavily implied.

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.