Jane’s head poked out, turtlelike, from behind the back of her chair. “Amy,” she whispered, “I don’t like that man.”

“Shhhhh!” Amy hissed. “Wait till we know they’re gone!”

“Unless they tiptoed back, I think we’re safe.”

Amy bounced up, and gave an extra little hop of glee, just for good measure. “Isn’t this exciting, Jane! What absolute luck! And if you hadn’t followed Edouard, we’d never have—”

Jane was clearly not listening, because she broke in with a worried, “That Mr. Marston is no gentleman.”

Amy glanced up from brushing dark smudges of dust off the satin of her dress. White was no color for a spy. “But, Jane, he must be the Purple Gentian! Who else could it be?”

“That doesn’t make him a gentleman. Besides, we don’t know he’s the Purple Gentian, Amy.” Amy didn’t need to see her cousin’s face to know what sort of look she was being given.

“Oh, Jane.” Before she gave way to pique, Amy recalled that her cousin hadn’t had the benefit of the keyhole. In tones that rapidly escalated from a whisper, she hastily repeated the conversation she had overheard. As Edouard had slammed the door to the marble gallery behind him, neither Amy nor Jane noticed an ear being pressed to the keyhole. Neither saw a pair of green eyes glitter like a panther on the prowl at the words “study,” and “tonight.”

Neither heard the sound of muffled footsteps easing down the marble gallery as Richard slipped away to plan a midnight raid on Balcourt’s study.

“So you see, Jane,” Amy finished, curls bouncing as she pirouetted around the small room, “I’ll just hide in Edouard’s study and eavesdrop on their conversation. Obviously, they couldn’t talk here with all of these revolutionaries about, but tonight . . .”

She had to make sure she got to Edouard’s study before he did.

“We’re so close, Jane!” she crowed. “I can’t believe we’ve already found the Purple Gentian!”

“Nor can I,” commented Jane uneasily.

Chapter Fifteen

Richard paused outside the window of Edouard de Balcourt’s study, tugging the hood of his black cloak further down around his face. He always felt deuced silly in this getup. Black breeches, black shirt, black cloak, black mask . . . It was the sort of outfit worn by pretentious highwaymen with names like the Shadow or the Midnight Avenger, who hoped to be written up in the illustrated papers with lines like, “His heart is of the same unrelieved black as his clothes. . . .” Ugh. If the black weren’t so bloody useful for blending into the night, Richard would have been much happier carrying out his missions in buff breeches. Besides, the mask tickled the bridge of his nose. Who ever heard of a sneezing spy?

Giving his nose one last good wriggle, Richard set his mask straight, and eased open the library window. The drapes had been left open, and unless Balcourt were lying on the floor in the dark—an image which boggled Richard’s excellent imagination—the study was clearly deserted. Good. He would have time to do a little scouting and hide himself properly before Balcourt and Marston met for their rendezvous. If Richard had timed it right, it should be roughly a quarter to twelve. From what he knew of Balcourt, he was just the sort of hackneyed individual who was bound to hold any clandestine meeting just at the stroke of midnight. Hell, if Balcourt were a spy, he would probably enjoy wearing all black.

That was one thing Balcourt had in common with his sister—an instinct for drama.

Grasping the windowsill in both hands, Richard hoisted himself up and into the room, just managing not to get his legs tangled in his cloak. He wobbled a bit as he landed on the squishy cushions of the window seat, hopping down onto the floor rather more rapidly than he had intended.

Richard scanned the room. The recessed windows with their thick velvet drapes would be his line of retreat if he heard footsteps in the hall. A desk, a small table bearing a brandy decanter, a standing globe . . . the furnishings of the room, while expensive, were few. How could a man have a study without bookshelves? The bibliophile in Richard was appalled. The only reading matter of any kind apparent in Edouard Balcourt’s study was a pile of well-thumbed fashion papers featuring the latest in waistcoats.

The obvious place to look would be the desk. But this desk was a spindly affair, little more than a glorified table, with room for only one narrow drawer. Besides, Balcourt might not be the brightest frog in the pond, but even he couldn’t possibly be dim enough to store evidence of illicit activities in his desk.

Of course, Delaroche stored his most sensitive files in his desk—or, rather, had stored his most sensitive files in his desk, Richard amended with a smug smile—but to be fair to Delaroche, he had done so on the assumption that the Ministry of Police was impenetrable, not out of rank stupidity.

If not the desk, then where?

Balcourt had hung paintings above his desk and above the table on the far side of the room. Both gleamed with newness. There had been no time for dust to colonize the curlicues in the gilded frames, nor were the surfaces of the paintings themselves dulled by sunlight or grime. In most of his investigations, Richard followed the rule that anything conspicuously new was automatically suspect. Trust Balcourt to be difficult. Everything in the study was conspicuously new. The desk, with brass sphinxes’ heads inlaid into the wood of the legs, couldn’t be more than a year old, if that, and the small table bearing the decanter, aside from being too thin to boast a false bottom, was clearly from the same workshop. Even the mantelpiece on the fireplace was a recent addition.

In fact, in the entire room, the only object not new, fashionable, and, to Richard’s mind, unpardonably ugly was the globe standing in the corner of the room, between the table and the window. There had been just such a globe in the library at Uppington Hall when Richard was young. Due to Richard’s habit as a beastly eight-year-old of spinning the globe as fast as he could make it go for the joy of seeing the countries blur into multicolored blobs, the Uppington Hall library globe was no more. It had spun off its moorings, smashed out the window, and ended its existence by bouncing into an ornamental fountain under the shocked gaze of a marble water maiden. Richard had been confined to paper maps for years.

It was with a certain amount of eight-year-old glee that Richard approached Balcourt’s globe.

Wrapping his fingers around the contours of the globe, Richard lifted it up off its stand and shook it. And shook it again, thrilling to the unmistakable swish of paper. Rather a lot of paper, unless he missed his guess. Huzzah!

His fingers probed for the catch, and he had just found a suspicious bump somewhere along the equator when Richard heard a bump of an entirely difference kind. And a noise that sounded curiously like the word “ouch.”

Dash it all, Balcourt wasn’t actually lying on the floor in the dark, was he?

Richard immediately dismissed the ridiculous thought. Balcourt’s voice might be squeaky, but he wasn’t a eunuch. Richard stood very still, weighing his options. That might not have been an ouch at all. It might have been a squeaky floorboard, or a mouse. Yet, if there were even the slightest chance of it being a human voice, the sensible thing to do was to dive out the window and make his escape before he was seen.

Being a sensible man, Richard intended to do just that.

He was quite surprised to hear his own voice whisper, in French, “Who’s there?”

And he was even more surprised when a voice answered, in the same language, “Don’t worry! It’s just me. Ouch!”

“Just me,” Richard repeated stupidly. A small and all-too-familiar figure was wriggling its way out from under the desk. “Dratted furniture!” he heard it mutter in English, as first a dark head and then a pair of shoulders slithered partway out. “Oh, blast, my hem’s caught.” The head disappeared again under the desk.

Too incredulous even to be angry, Richard stalked over to the desk, grabbed a pair of slim forearms, and pulled. There was a slight tearing sound, and out popped a rather disheveled Miss Amy Balcourt.

Amy didn’t yelp as the Purple Gentian dragged her out from under her brother’s desk. She didn’t even wince when her knee scraped against the carpet. She was too busy staring unabashedly at the Purple Gentian.

The Purple Gentian was here, in the flesh, in her brother’s study. True, not much flesh was revealed by the long black gloves, black mask, black pants, black cloak, and black hood, but two very lively eyes blazed through the holes of his mask, and his black-garbed chest rose and fell with his somewhat uneven breathing.

Despite her confident words to Jane earlier—one had to be confident with Jane, or else she logicked one to the point of despair—Amy had feared that her sojourn under the library desk would go unrewarded, unless one counted the gleaning of a fine crop of dust. The Purple Gentian, savior of royalists, scourge of the French, had haunted her daydreams for so long that it seemed scarcely possible that he could appear in any form more material than that of a phantom.

But here he was, real, alive, from his scuffed boots to the expression of shocked outrage on his shadowed face. Amy didn’t even have to pinch herself to make sure she wasn’t dreaming because the Gentian, unintentionally, had undertaken that task for her. The grip of his gloved fingers on her upper arms was painfully tight. Amy wiggled a bit in the Gentian’s grasp as she began to lose feeling in her fingers.

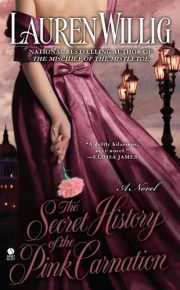

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.