Richard closed his eyes and pressed the heel of his hand hard against his forehead. “So it wasn’t Deirdre, it was her bloody French maid who was the spy. That didn’t make any difference to Tony.”

“It exonerated her of ill intent.”

“But not me of idiocy.” Richard’s green eyes darkened with remembered pain. “Don’t you see? That makes it that much worse. A chance word to her maid while she was fixing her hair—her damned hair!—and Tony’s life was forfeit. Say I tell Amy . . .”

“So that’s her name.”

“And Amy makes some comment—in strictest secrecy, because, of course, these things are always passed along in strictest secrecy,” Richard spat out, “to her cousin Jane. Jane’s a discreet sort of girl; she might not repeat it. But the house is teeming with servants. Even if they don’t have a bloody lady’s maid in the room with them, there’s bound to be a footman lurking somewhere about. And then there’s Balcourt himself, who may or may not be on Bonaparte’s payroll, but who would do anything to ingratiate himself to him. How long would the League of the Purple Gentian last if my identity were to become known to him? I give it the time it would take for him to call his carriage and waddle his way to the consul’s study.” Richard raised his wineglass in an ironic salute. “Farewell, Purple Gentian.”

“That’s only the very worst case.”

Richard’s lips twisted in a humorless smile. “Isn’t that what we ought to plan for then? I can’t risk it, Geoff. Even if there weren’t other impediments, I couldn’t risk it. Too many people depend on me.”

Geoff looked at him steadily, a friend of too long standing to be daunted by either irony or idealism. “You know what Miles would tell you if he were here. He’d say, ‘You’re being too bloody noble.’ And, in this instance, he’d be right.”

Breaking Geoff’s gaze, Richard lounged back in his chair and changed the subject. “Did anything else thrilling transpire while I was away? Like Delaroche choking on a chicken bone?”

Geoff pushed aside the remains of his own cold chicken. “Delaroche, I regret to inform you, is still alive and kicking. I must say, the man does have an instinct for theater. He strode into the Tuilleries the other day and informed Bonaparte that, as the Purple Gentian hadn’t struck for over a fortnight, it was clear that he, Delaroche, had scared him away.”

“That will never do,” Richard drawled. He rocked back and forth in his chair, a devilish gleam creeping into his emerald eyes. “After all, it would be deuced unkind of us to let the man continue to entertain these delusions, wouldn’t you say?”

Geoff hunched forward, his own eyes taking on an answering sheen. “What do you think one might do to disabuse him of these unhealthy fantasies?”

“Well . . .” Richard toyed with the stem of his wineglass, admiring the way the candlelight struck crimson glints off the dark liquid. “One might raid his secret files . . . but one has done that already, so what’s the fun in that?”

“Or,” Geoff mused, getting into the spirit of the game, “one might leave mocking notes on his pillow, but . . .”

“One has done that already, too,” Richard concluded sadly. “Does Delaroche have any files we haven’t looked at yet?”

Geoff shook his head. “No. I’d say you made a rather thorough job of that. How about rescuing someone from the Temple prison? We haven’t done that in a while, and it’s sure to infuriate Delaroche.”

“The very thing!” Richard rocked upright so fast that he banged into the table, setting dishes and cutlery jumping. “I knew I kept you around for a reason!”

Geoff grimaced. “You flatter me.”

“Think nothing of it,” Richard advised him graciously. “Young Falconstone has been imposing on the hospitality of the Bastille for far too long. We wouldn’t want to overstrain their supplies.”

“The moldy bread and moldier water?”

“Don’t forget the occasional rat as a treat on holidays. I’m sure the French consider it a great delicacy. Like frogs, or cow’s brains.”

Geoff groaned. “No wonder they had a revolution! They were probably all suffering from chronic indigestion.”

“There may be something in that theory.” Richard pushed back from the table and stood. “But let’s save writing your History of the Causes of the French Revolution for another night. We have far more diverting activities ahead of us. . . .”

Chapter Twelve

In a little room in the Ministry of Police, a man stood looking out the window. His hands were clasped loosely behind his back, fingers and arms relaxed. The hair combed forward on his forehead in the classical style gave him the serene air of a bust of a Roman senator, a man of calm and gravitas. But when he spoke, his voice shook with controlled rage.

“This has gone on too long, Delaroche. Bonaparte is displeased. I am displeased. This man cannot be allowed to make us the laughingstock of Europe.” The Minister of Police slowly turned and fixed icy eyes on his subordinate. “What do you intend to do about it?”

“Kill him.”

A whir of movement, and a silver-handled letter opener quivered as if in fear, its point embedded in the blotter of Delaroche’s desk. The sentry at the door cringed back, but Fouché regarded the palpitating knife with a jaundiced eye. “That’s all very well, but you have to find him first, do you not? How many years has it been, Delaroche? Four? Five?”

“He won’t live to see another.” Delaroche’s sallow countenance burned with the fanatic fervor of a sixteenth-century inquisitor. “I’ll draw up a short list of suspects. My best men will shadow them day and night. They won’t so much as piss but we’ll know of it! He will not slip through my fingers again. I’ll have him strung up before you within the month.” Delaroche’s lips curled into a feral snarl.

“See that you do,” Fouché said coolly. “The invasion of England relies on the strictest secrecy. We cannot afford any more breaches of security.”

Reaching over, he retrieved his hat from the corner of Delaroche’s desk. “We can only hope that the papers have not yet gotten wind of this latest embarrassment. I suggest you hold to your promise, or the Purple Gentian may not be the only man to swing. Good day, Delaroche.”

The door clicked smartly shut behind the Minister of Police.

Delaroche stalked over to his desk, flipped back the tails of his coat, and sat down heavily. On the blotter, where Fouché had tossed it upon his entrance, lay a small, cream-colored card.

Fingers steepled in front of him, Delaroche stared at the note. The card itself was useless. Delaroche had an entire drawer full of nothing but cream-colored cards bearing the Gentian’s distinctive purple stamp. He had long ago traced the cards to a very exclusive stationer in London which boasted a wide clientele among the ton. If Delaroche were to go on the make of the paper alone, he could easily accuse anyone from the Prince of Wales to Lady Mary Wortley Montague. Inside—Delaroche did not need to release the card from the letter opener to look; he recalled the contents in painful detail—inside, that rogue had inscribed a bill for the accommodations. One shilling for stale bread, one shilling for rank water, two shillings for rats, three shillings for amusing insults from the guards, and so on, before signing it with the customary small purple flower. On top of the note had been a small pile of English coins, as per the reckoning.

Damn him! The list was in Falconstone’s hand—Delaroche knew the handwriting of every man whose correspondence he had ever intercepted. Delaroche could picture the Gentian standing there, dictating, in the middle of the most carefully guarded prison in Paris. The man’s cheek was unbelievable.

Which would make killing him all the sweeter.

Reaching into a desk drawer, Delaroche retrieved a plain sheet of writing paper. He dabbed a quill savagely into the inkpot, wishing it were a knife plunging into the Gentian’s heart. He would have that pleasure soon enough. The man had played him for a fool one too many times. Delaroche had enjoyed the game; he would be the last to deny that. He had enjoyed the excitement of an adversary worthy of his attention—most of these would-be spies were pitifully easy to discover, and even more pitifully easy to coerce into full disclosure. A few fingernails pulled and they babbled like babes. Pathetic.

Attacking the paper with an explosion of inkblots, Delaroche scrawled the first name on his list: Sir Percy Blakeney, Baronet.

The Gentian had to be an Englishman, of that Delaroche was sure. Only an Englishman would have such an utterly inappropriate sense of humor. Who else but an Englishman would disguise himself as a dancing bear or leave itemized payment for a jailer? Those English! Didn’t they realize that espionage was no laughing matter?

During his time as the Scarlet Pimpernel, Sir Percy had played similar jokes on the French government. He still spent large parts of each year in Paris with his French wife. He was even now in residence in his town house in the Faubourg St. Germain. He was, of course, kept under close surveillance, but hadn’t the Scarlet Pimpernel eluded the closest of surveillance before? Bonaparte insisted that Sir Percy was harmless, a serpent whose fangs had been drawn. Bonaparte found him amusing. Delaroche found him highly suspect. Like the London news sheets, he had always retained a nagging suspicion that Sir Percy had changed only his nom de guerre, not his spots.

Delaroche returned to his list. Unlike the London news sheets, he did not proceed to name Beau Brummel (after an unpleasant encounter with the man in London, Delaroche had concluded that Brummel was, indeed, quite that interested in fashion). Instead, Delaroche penned the name Georges Marston.

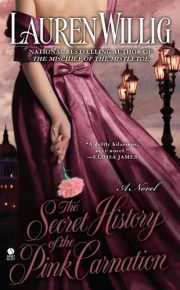

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.