“There is that,” Geoff conceded. “But Stiles heard from Fouché’s butler that the Ministry of Police has been very quietly detailing men to guard shipments of something coming in from Switzerland. He wasn’t sure what, and he didn’t know when—at least not yet—but he did say that it was top priority, whatever it was.”

“That does sound promising, if somewhat vague. I take it you’ve had someone watching the major roads and waterways?”

“I will ignore the implicit insult,” Geoff said calmly. “Yes, I have. In addition to another three cases of brandy in the cellar, we also have a few leads. Whatever these shipments are, Georges Marston is up to his neck in it.”

Richard’s lip curled in distaste. “Why does that come as no surprise?” he inquired of the portrait on the wall behind Geoff’s head.

The portrait, presumably an ancestor of the former owner of the house, which Richard had purchased furnished, sneered silently. One might assume that the gentleman in the portrait would have turned up his nose at the likes of Marston, even had he been able to speak. While Marston claimed a relation with a distinguished English family through his father, it was an open secret that he had been raised by his French mother in circumstances that could hardly be called respectable. Having wrangled his father’s family into buying him a commission in the English army, he had promptly deserted in the midst of battle and decamped to the French.

“Marston has been frequenting the docks,” Geoff continued. “I’ve had our boys watching him. We’ve noticed a pattern—every few days, someone will come to his lodgings with a note, and then he hares off in a carriage to the waterfront.”

“Then what? Oh, devil take it!” Richard mopped at his lap, where a little puddle of soup was collecting from the spoon that he had suspended halfway to his lips.

“Not the devil, Marston,” Geoff corrected with a twitch of his lips. “I hope those weren’t new trousers?”

Richard scowled.

“At any rate,” Geoff went on, “he always takes an unmarked black coach and four—”

“I thought he only had that flashy curricle of his.” Richard made sure to put his soup spoon down before speaking. “That hideous bright red thing.”

“It wouldn’t be at all bad if it weren’t for the color,” commented Geoff wistfully.

“Marston?” Richard prompted.

“Right.” Geoff shook himself out of his reverie of curricles and phaetons. “The use of the carriage heightened our suspicions. We traced it to a livery stable not far from Marston’s lodgings.”

“The curricle would be too noticeable,” mused Richard. Seeing the gleam of the carriage lover rekindle in Geoff’s eye, Richard hastily asked, “What does he do once at the docks?”

“Cleverly disguised as a sailor, I followed Marston to a rather disreputable tavern called the Staves and Cutlass. They named it that for good reason, I might add,” Geoff commented thoughtfully. “It was quite a good thing that I was wearing a hook.”

“And there I was with the debutantes while you were having all the fun,” mourned Richard.

“Calling it fun might be stretching matters a bit. When I wasn’t otherwise occupied in retaining my skin in one piece, I did notice Marston first engage in conversation with a bunch of ruffians, and then slip into a back room. When he didn’t return, I left the establishment just in time to see Marston and his cronies finish loading the carriage with a number of brown paper packages.”

“What were they?”

Geoff cast Richard a mildly exasperated look. “If we knew that, why would we still be following him? However, I can tell you that at least some of the shipments have made their way to the Hotel de Balcourt.”

“Balcourt?”

“You know, little toady of a man, always hanging about the Tuilleries,” Geoff clarified.

“I know who you mean,” Richard said through a mouthful of soup. Swallowing, he explained, “It’s just a devilish odd coincidence. I shared a boat—and a carriage—with Balcourt’s sister and cousin.”

“I didn’t realize he had a sister.”

“Well, he does.” Richard abruptly pushed away his empty bowl.

“What a great stroke of luck! Could you use the acquaintance with the sister to discover more about Balcourt’s activities?”

“That,” Richard said grimly, “is not an option.”

Geoff eyed him quizzically. “I realize that any sister of Balcourt’s is most likely repugnant at best, but you don’t need to propose to the girl. Just flirt with her a bit. Take her for a drive, call on her at home, use her as an entrée into the house. You’ve done it before.”

“Miss Balcourt is not repugnant.” Richard twisted in his chair, and stared at the door. “What the devil is keeping supper?”

Geoff leaned across the table. “Well, if she’s not repugnant, then what’s the—ah.”

“Ah? Ah? What the deuce do you mean by ‘ah’? Of all the nonsensical . . .”

“You”—Geoff pointed at him with fiendish glee—“are unsettled not because you find her repugnant, but because you find her not repugnant.”

Richard was about to deliver a baleful look in lieu of a response, when he was saved by the arrival of the footman bearing a large platter of something covered with sauce. Richard leaned forward and speared what looked like it might once have been part of a chicken, as the footman whisked off with his soup dish.

“Have some,” Richard suggested to Geoff, ever so subtly diverting the conversation to culinary appreciation.

“Thank you.” Undiverted, Geoff continued, “Tell me about your Miss Balcourt.”

“Leaving aside the fact that she is by no means my Miss Balcourt”—Richard ignored the sardonic stare coming from across the table—“the girl is as complete an opposite to her brother as you can imagine. She was raised in England, somewhere out in the countryside. She’s read Homer in the original Greek—”

“This is serious,” murmured Geoff. “Is she comely?”

“Comely?”

“You know, nice hair, nice eyes, nice . . .” Geoff made a gesture that Richard would have expected more readily from Miles.

“She doesn’t look like her brother, if that’s what you’re asking,” Richard bit out.

Geoff slapped the table. “But if you’re taken with her, that’s wonderful!” His lips twitched. “You can court her and investigate her brother at the same time.”

Richard gave the napkin he had just lifted to his lips an irritable twitch. “No, I cannot. First of all, you know that I will never again allow my personal life to interfere with a mission. And secondly . . . secondly,” he repeated more loudly, as Geoff opened his mouth to protest, “did I forget to mention that she hates me?”

“That’s quick work. How did you get her to hate you in all of one day?”

“It was a day and a half.”

Something between a snort and a snicker escaped Geoff’s lips.

“Easy for you to laugh,” retorted Richard.

“No arguing with that,” chuckled Geoff. “No, really, what did you do?”

Richard planted his elbows on the polished wood of the table. “I told her I worked for Bonaparte.”

“And that was all?”

Richard’s lips quirked. “She’s rather passionate on the subject of the Revolution.”

“Then why is she—”

“I know, I know, I asked her the same thing.”

“And you won’t tell her—”

“No!” Richard pushed back from the table so hard that the legs of his chair nearly splintered.

“You could let me finish a sentence once in a while, you know,” Geoff said mildly.

“Sorry,” Richard muttered.

Geoff took advantage of Richard’s momentary silence to say, “I’m not suggesting you go shouting your identity to every comely young lady who wanders your way. But if this one is special, wouldn’t it be better to take the chance of confiding in her—in a limited way,” he added hastily, “than risk losing her? If she’s so fanatical about the Revolution, it seems rather unlikely that she would betray you.”

Richard was mustering his objections when Geoff silenced him again with the softly spoken words, “Not every woman is as shallow as Deirdre.”

Richard pressed his lips together. “You sound like my mother.”

“Since I like your mother, I’ll take that as a compliment, and not as the insult for which it was intended.” Geoff leaned both elbows on the table. “In some ways, it was a fortunate escape for you.”

“But not for Tony.”

“You can’t go on blaming yourself for Tony’s death. Good gad, the odds of something like that happening were nonexistent! It was an accident, Richard, a foolish, unfortunate accident.”

“It would never have happened if infatuation hadn’t impeded my judgment.”

Richard remembered the nervous anticipation he had felt each time he galloped over to call on Deirdre, the way the heady scent of her perfume made his pulse race and his head spin. Funny, he couldn’t remember exactly what she looked like. He had once written a sonnet to her blue, blue eyes, but he could recall the sonnet, with its limping meter and forced rhymes, far better than he could the eyes themselves. And yet this fuzzy image of a woman, so utterly unmemorable now, had exercised a strong enough effect on him to make him completely forget his obligations. Let this be a lesson to you, he advised himself. Passion was fleeting; dishonor lingered. Sic transit . . . well, everything.

Richard tried to think of a more fitting Latin tag, but couldn’t. Amy would probably . . . Richard quelled that counterproductive thought before it could go any further.

Geoff poured himself a second cup of claret. “Besides, as hideously as the business with Deirdre ended, she wasn’t malicious, just henwitted. It was pure ill luck that her maid happened to be a French operative.”

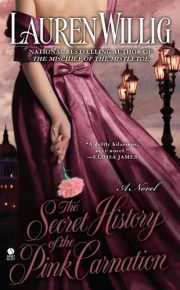

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.