A thin stick of a man in a long brown robe shuffled out from behind an oak counter. His face was as wrinkled as a walnut, with a long tufty beard on the point of his chin, and he still wore his hair in the old-fashioned Manchu queue that trailed like a grey snake down his back. His eyes were black and shrewd.

‘Welcome, Missy, to my humble business. It does my worthless heart good to set eyes on you again.’ He bowed politely and she returned the courtesy.

‘I came because all Junchow says that only Mr Liu knows the true value of beautiful craftsmanship,’ Lydia said smoothly.

‘You do me honour, Missy.’ He smiled, pleased, and gestured toward the low table in the corner. ‘Please, sit. Refresh yourself. The summer rains are cruel this year and the gods must be angry indeed, for they breathe fire down on us each day from the sky. Let me bring you a cup of jasmine tea to soothe the heat from your blood.’

‘Thank you, Mr Liu. I’d like that.’

She sat down on a bamboo stool and slipped a peanut into her mouth as soon as his back was turned. While he busied himself behind a screen inlaid with ivory peacocks, Lydia’s gaze inspected the shop.

It was dark and secretive, its dusty shelves so crowded with objects they tumbled over each other. Fine Jiangxi porcelain, hundreds of years old, lay next to the very latest radio in shiny cream Bakelite. Delicately painted scrolls hung from a ferocious Boxer sword and above them a strange twisted tree made of bronze seemed to grow out of the top of a grinning monkey’s head. On the opposite side two German teddy bears leaned against a row of silk top hats handmade in Jermyn Street. A weird contraption of wood and metal springs was propped up beside the door and it took Lydia a moment to realise it was a false leg.

Mr Liu was a pawnbroker. He bought and sold people’s dreams and oiled the wheels of daily existence. Lydia let her eyes glide over the rail at the back of the shop. That was where she loved to linger. A glittering array of elegant evening gowns and fur coats, so many and so heavy that the rail bowed in the middle as if flexing its back. Just the sight of such luxury made Lydia’s young heart give a sharp little skip of envy. Before she left the shop she always made a point of sidling over there to run her hand through the dense furs. A glossy muskrat or a honey mink, she had learned to recognise them. One day, she promised herself, things would be different. One day she’d be buying, not selling. She’d march right in here with a bucketload of dollars and whisk one of these away. Then she’d drape it around her mother’s shoulders and say, ‘Look, Mama, look how beautiful you are. We’re safe now. You can smile again.’ And her mother would give a glorious laugh. And be happy.

She slipped two more peanuts into her mouth and started tapping her tight little black shoe on the tiles with impatience.

At once Mr Liu reappeared with a tray and a watchful smile. He placed two tiny wafer-thin cups without handles on the table alongside a teapot. It was unglazed and looked very old. In silence the old man filled the cups. Oddly, the aroma of jasmine blossom that rose from the stream of hot liquid did indeed soothe the heat from Lydia’s mind and she was tempted to place her find on the table right there and then. But she knew better. Now they would gossip. This was the way the Chinese did business.

‘I trust you are keeping in good health, Missy, and that all is well within the International Settlement in these troubled times.’

‘Thank you, Mr Liu, I am well. But in the Settlement…’ She gave what she hoped was a woman-of-the-world shrug. ‘There is always trouble.’

His eyes brightened. ‘Was the Summer Ball at Mackenzie Hall not a success?’

‘Oh yes, of course it was. Everyone was there. So elegant. All the grandest motorcars and carriages. And jewels, Mr Liu, you would have appreciated the jewels. It was just so…,’ she could-n’t quite keep the wistfulness out of her voice, ‘so perfect.’

‘I am indeed pleased to hear it. It is good to know the many nations who rule this worthless corner of China can meet together for once without cutting each other’s throats.’

Lydia laughed. ‘Oh, there were plenty of arguments. Around the gaming tables.’

Mr Liu bent a fraction closer. ‘What was the subject of the dispute?’

‘I believe it was…,’ she paused deliberately to sip the last of her tea, keeping him hanging there, listening to his breath coming in short expectant gasps, ‘… something to do with bringing over more Sikhs from India. They want to reinforce the municipal police, you see.’

‘Are they expecting trouble?’

‘Commissioner Lacock, our chief of police, said it was just a precaution because of the looting going on in Peking. And because so many of your people are pouring into our Junchow International Settlement in search of food.’

‘Ai-ya, we are indeed in terrible times. Death is as common as life. Starvation and famine all around us.’ He let a small silence settle between them, like a stone in a pond. ‘But explain to my dull brain, if you would, Missy, how someone like you, so young, is invited to attend this most illustrious occasion at Mackenzie Hall?’

Lydia blushed. ‘My mother,’ she said grandly, ‘was the finest pianist in all Russia and played for the tsar himself in his Winter Palace. She is now in great demand in Junchow. I accompany her.’

‘Ah.’ He bowed respectfully. ‘Then all is clear.’

She didn’t much like the way he said that. She was always wary of his impressive command of English and had been told that he was once the compradore for the Jackson & Mace Mining Company. She could imagine him with a pickaxe in one hand and a lump of gold in the other. But it was whispered he had left under a cloud. She glanced at the shelves and the pad-locked display case of sparkling jewellery. In China, thieving was not exactly unknown.

Now it was her turn.

‘And I hope that the increase of people in town will bring advantages to your own business, Mr Liu.’

‘Ai! It pains me to say otherwise. But business is so poor.’ His small dark eyes drooped in exaggerated sorrow. ‘That son of a dung snake, Feng Tu Hong, the head of our new council, is driving us all into the gutter.’

‘Oh? How is that?’

‘He demands such high taxes from all the shops of old Junchow that it drains the blood from our veins. It is no surprise to my old ears to hear that the young Communists skulk around at night putting up their posters. Two more were beheaded in the square yesterday. These are hard times, Missy. I can hardly find enough scraps to feed myself and my worthless sons. Ai-ya! Business is very bad, very bad.’

Lydia managed to bite back her smile.

‘I grieve for you, Mr Liu. But I have brought you something that I hope will help your business become successful once again.’

Mr Liu inclined his head. A signal that the time had come.

She put her hand in her pocket and drew out her prize. She laid it on the ebony table where it gleamed as bright as a full moon. The watch was beautiful, even to her untutored eyes, and from its handsome gilt case and heavy silver chain drifted the smell of money. She observed Mr Liu carefully. His face did not move a muscle, but he failed to keep the brief flash of desire out of his eyes. He turned his face away from it and slowly sipped his tiny cup of tea. But Lydia was used to his ways, ready for his little tricks.

She waited.

Finally he picked it up and from his gown produced an eyeglass to inspect the watch more closely. He eased open the front silver cover, then the back and the inner cover, murmuring to himself under his breath in Mandarin, his hands caressing the case. After several minutes he replaced it on the table.

‘It is of some slight value,’ he said indifferently. ‘But not much.’

‘I believe the value is more than slight, Mr Liu.’

‘Ah, but these are hard times. Who has money for such things as this when there is no food on the table?’

‘It is lovely craftsmanship.’

His finger moved, as if it would stroke the silver piece once more, but instead it stroked his little beard. ‘It is not bad,’ he admitted. ‘More tea?’

For ten minutes they bargained, back and forth. At one point Lydia stood up and put the watch back in her pocket, and that was when Mr Liu raised his offer.

‘Three hundred and fifty Chinese dollars.’

She put the watch back on the table.

‘Four hundred and fifty,’ she demanded.

‘Three hundred and sixty dollars. I can afford no more, Missy.

My family will go hungry.’

‘But it is worth more. Much more.’

‘Not to me. I’m sorry.’

She took a deep breath. ‘It’s not enough.’

He sighed and shook his head, his long queue twitching in sympathy. ‘Very well, though I will not eat for a week.’ He paused and his sharp eyes looked at her assessingly. ‘Four hundred dollars.’

She took it.

Lydia was happy. She sped back through the old town, her head spinning with all the good things she would buy – a bag of sugary apricot dumplings to start with, and yes, a beautiful silk scarf for her mother and a new pair of shoes for herself because these pinched so dreadfully, and maybe a…

The road ahead was blocked. It was a scene of utter chaos, and crouching at the heart of it was a big black Bentley, all wide sweeping fenders and gleaming chrome work. The car was so huge and so incongruous in the narrow confines of streets designed for mules and wheelbarrows that for a moment Lydia couldn’t believe she was seeing straight. She blinked. But it was still there, jammed between two rickshaws, one lying on its side with a fractured wheel, and up against a donkey and cart. The cart had shed its load of white lotus roots all over the road and the donkey was braying to get at them. Everyone was shouting.

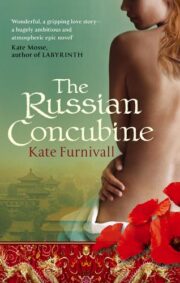

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.