The Englishman turned back to the stallholder and, with a shrug of despair, asked again, ‘How do you do it?’

The Chinese vendor gazed up at the tall fanqui, the Foreign Devil, with a total lack of comprehension, but he had promised his new concubine a pair of satin slippers today, red embroidered ones, so he was reluctant to lose a sale. He repeated two of his eight words of English. ‘You buy?’ and added hopefully, ‘So nice.’

‘No.’ The Englishman lovingly replaced the bowl beside a black-and-white lacquered tea caddy. ‘No buy.’

He turned away but was allowed no peace. Instantly accosted by the next stallholder. The flow of chatter, in that damn language he couldn’t understand, sounded to his large Western ears like cats fighting. It was this blasted heat. It was getting to him. He mopped his brow with his handkerchief and checked his pocket watch. Time to make tracks. Didn’t want to be late for his luncheon appointment with Binky Fenton at the Ulysses Club. Bit of a stickler about that sort of thing, was old Binky. Quite right too.

A sharp pain cut into his shoulder. A rickshaw was squeezing past, clattering over the cobbles. Damn it, there were just too many of the darn things. Shouldn’t be allowed. His eyes flicked toward the occupant of the rickshaw with irritation, but instantly softened. Sitting very upright, slender in a high-necked lilac cheongsam, was a beautiful young Chinese woman. Her long dark hair hung like a cloak of satin far down her back and a cream orchid was fastened behind her ear by a mother-of-pearl comb. He couldn’t see her eyes, for they were lowered discreetly as she gazed down at her tiny hands on her lap, but her face was a perfect oval. Her skin as exquisite as the porcelain bowl he’d held in his hands earlier.

A rough shout dragged his attention to the struggling rickshaw coolie, but he averted his eyes with distaste. The fellow was wearing nothing but a rag on his head and a filthy loincloth round his waist. No wonder she preferred to look at her folded hands. It was disgusting the way these natives flaunted their naked bodies. He raised his handkerchief to his nose. And the smell. Dear God, how did they live with it?

A sudden shrill blare of a brass trumpet made him jump. Rattled his nerves. He stumbled back against a young European girl standing behind him.

‘I’m so sorry, miss.’ He touched his panama hat in apology. ‘Please excuse my clumsiness. That vile noise got the better of me.’

She was wearing a navy blue dress and a wide-brimmed straw hat that hid her hair and shaded her face from him, but he gained the distinct impression she was laughing at him because the trumpet proved to be nothing more than the local knife grinder’s way of announcing his arrival in the market. With a curt nod, he crossed the street. The girl shouldn’t be there anyway, not without a chaperone. His thoughts were sidetracked by the sight of a carved image of Sun Wu-kong, the magical monkey god, on one of the other stalls, so he did not stop to ask himself what possible reason an unattended white girl could have for being alone in a jostling Chinese market.

Lydia’s hands were quick. Her touch was soft. Her fingers could lift the smile from the Buddha himself and he’d never know.

She slid away into the crowd. No backward glance. That was the hardest part. The urge to turn and check that she was in the clear was so fierce it burned a hole in her chest. But she clamped a hand over her pocket, ducked under the jagged tip of the water carrier’s shoulder pole, and headed toward the carved archway that formed the entrance to the market. Stalls piled high with fish and fruit lined both sides of the street, so that where it narrowed at the far end, the crush of people deepened. Here she felt safer.

But her mouth was dry.

She licked her lips. Risked a quick glance back. And smiled. The cream suit was exactly where she’d left him, bent over a stall and fanning himself with his hat. Her sharp eyes picked out a young Chinese street urchin wearing what looked like coarse blue pyjamas, loitering meaningfully right behind him. The man had no idea. Not yet. But at any moment he might decide to check his pocket watch. That’s what he’d been doing when she first spotted him. The stupid melon-head, didn’t he have more sense?

She’d known straight off. This one was going to be easy.

A little sigh of pleasure escaped her. And it wasn’t only the adrenaline talking after she’d made a good nab. Just the sight of the Chinese market spread out before her gave her a kick of delight. It was the energy of it she adored. Teeming with life in every corner, bursting out in noise and clatter, in the high-pitched cries of the vendors and in the bright yellows and reds of the persimmons and watermelons. It was in the flow of the rooftops, the way they curled up at the edges as if trying to hook a ride on the wind, and in the loose free-moving clothes of the people below as they haggled for crayfish or bowls of baked eels or an extra jin of alfalfa shoots. It was as if the very smell of the place had seeped into her blood.

Not like in the International Settlement. There, it seemed to Lydia, they had whalebone corsets clamped round their minds as well as round their bodies.

She moved fast. But not too fast. She didn’t want to attract attention. Though foreigners in the native markets were not uncommon, a fifteen-year-old girl on her own certainly was. She had to be careful. Ahead of her lay the broad paved road back to the International Settlement and that’s exactly where the cream suit would expect to find her if he came looking. But Lydia had other plans. She turned sharp right.

And ran straight into a policeman.

‘Okay, miss?’

Her heart hammered against her ribs. ‘Yes.’

He was young. And Chinese. One of the municipal recruits who patrolled proudly in their smart navy uniform and shiny white belt. He was looking at her curiously.

‘You lost? Young ladies not come here. Not suitable.’

She shook her head and treated him to her sweetest smile. ‘No, I’m meeting my amah here.’

‘Nurse ought know better.’ He frowned. ‘Not good. Not good at all.’

An angry shout suddenly rang out from the marketplace behind Lydia and she was all set to run, but the policeman had lost interest. He touched his cap and hurried past her into the crowded square. Instantly she was off. Up the steep stone steps. Under the stone arch that would take her deep into the heart of the old Chinese town with its ancient walls guarded by four massive stone lions. She didn’t dare come here often, but at times like this it was worth the risk.

It was a world of dark alleyways and darker hatreds. The streets were narrow. Cobbled and slippery, dirty with trampled vegetables. To her eyes the buildings had a secretive look, hiding their whispers behind high stone walls. Or else low and squat, lurching against each other at odd angles, next to tearooms with curling eaves and gaily painted verandas. Grotesque faces of strange gods and goddesses leered down at her from unexpected niches.

Men carrying sacks passed her, and women carrying babies. They stared at her with hostile eyes, said things to her she couldn’t understand. But more than once she heard the word fanqui, Foreign Devil, and it made her shiver. On one corner an old woman, wrapped in rags, was begging in the dirt, her hand stretched out like a claw, tears running unchecked down the deep lines of her skeletal face. It was a sight Lydia had seen many times, even on the streets of the International Settlement in recent days. But it was one she could never get used to. They frightened her, these beggars. They threw her mind into panic. She had nightmares where she was one of them, in the gutter. Alone, with only worms to eat.

She hurried. Head down.

To reassure herself she wrapped her fingers round the heavy object in her pocket. It felt expensive. She longed to inspect her spoils but it was far too dangerous here. Some local tong member would chop her hand off as soon as look at her, so she forced herself to be patient. But still the tiny hairs on the back of her neck stood up. Only when she reached Copper Street did she breathe more easily and the sick churning in the pit of her stomach begin to subside. That was the fear. Always the same after she’d made a nab. Trickles of sweat ran down her back and she told herself it was because of the heat. She tweaked her scruffy hat to a smarter angle, glanced up at the flat white sky that lay like a stifling blanket over the whole of the ancient town, then set off toward Mr Liu’s shop.

It was set back in a dingy porch. The doorway was narrow and dark but its shop window gleamed bright and cheerful, surrounded by red latticework and draped with elegantly painted hanging scrolls. Lydia knew it was all part of the Chinese need for face. The façade. But what went on behind the public face was a very private matter. The interior was barely visible. She didn’t know what the time was but was sure she had overrun the hour allotted for lunch. Mr Theo would be angry with her for being late back to class, might even take a ruler to her knuckles. She had better hurry.

But as she opened the shop door, she could not resist a smile. She might be only fifteen, but already she was aware that expecting to hurry a Chinese business deal was as absurd as trying to count the fluttering pigeons that wheeled through the sky above the grey tiled roofs of Junchow.

Inside, the light was dim and it took a few moments for Lydia’s eyes to adjust. The smell of jasmine hung in the air, cool and refreshing after the humid weight of the air in the streets outside. The sight of a black table in one corner with a bowl of fried peanuts on it reminded her that she had eaten nothing since a watery spoonful of rice porridge that morning.

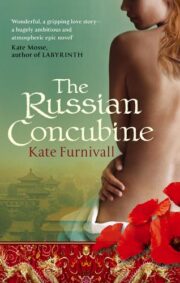

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.