At a nod of his head, the soldiers started to move among the prisoners. Systematically they seized all jewellery, all watches, all silver cigar cases, anything that had any worth, including all forms of money. Insolent hands searched clothing, under arms, inside mouths, and even between breasts, seeking out the carefully hidden items that meant survival to their owners. Valentina lost the emerald ring secreted in the hem of her dress, while Jens was stripped of his last gold coin in his boot. When it was over, the crowd stood silent except for a dull sobbing. Robbed of hope, they had no voice.

But the officer was pleased. The look of distaste left his face. He turned and issued a sharp command to the man on horseback behind him. Instantly a handful of mounted soldiers began to weave through the crowd, dividing it, churning it into confusion. Valentina clung to the small hand hidden in hers and knew that Jens would die before he released the other one. A faint cry escaped from the child when a big bay horse swung into them and its iron-shod hooves trod dangerously close, but otherwise she hung on fiercely and made no sound.

‘What are they doing?’ Valentina whispered.

‘Taking the men. And the children.’

‘Oh God, no.’

But he was right. Only the old men and the women were ignored. The others were being separated out and herded away. Cries of anguish tore through the frozen wasteland and somewhere on the far side of the train a wolf crept forward on its belly, drawn by the scent of blood.

‘Jens, no, don’t let them take you. Or her,’ Valentina begged.

‘Papa?’ A small face emerged between them.

‘Hush, my love.’

A rifle butt thumped into Jens’s shoulder just as he flicked his coat back over his daughter’s head. He staggered but kept his feet.

‘You. Get over there.’ The soldier on horseback looked as if he were just longing for an excuse to pull the trigger. He was very young. Very nervous.

Jens stood his ground. ‘I am not Russian.’ He reached into his inside pocket, moving his hand slowly so as not to unsettle the soldier, and drew out his passport.

‘See,’ Valentina pointed out urgently. ‘My husband is Danish.’

The soldier frowned, uncertain what to do. But his commander had sharp eyes. He instantly spotted the hesitation. He kicked his horse forward into the panicking crowd and came up alongside the young private.

‘Grodensky, why are you wasting time here?’ he demanded.

But his attention was not on the soldier. It was on Valentina. Her face had tilted up to speak to the mounted soldat and her hood had fallen back, revealing a sweep of long dark hair and a high forehead with pale flawless skin. Months of starvation had heightened her cheekbones and made her eyes huge in her face.

The officer dismounted. Up close, they could see he was younger than he had appeared on horseback, probably still in his thirties, but with the eyes of a much older man. He took the passport and studied it briefly, his gaze flicking from Valentina to Jens and back again.

‘But you,’ he said roughly to Valentina, ‘you are Russian?’

Behind them shots were beginning to sound.

‘By birth, yes,’ she answered without turning her head to the noise. ‘But now I am Danish. By marriage.’ She wanted to edge closer to her husband, to hide the child more securely between them, but did not dare move. Only her fingers tightened on the tiny cold hand in hers.

Without warning, the officer’s rifle slammed into Jens’s stomach and he doubled over with a grunt of pain, but immediately another blow to the back of his head sent him sprawling onto the snow. Blood spattered its icy surface.

Valentina screamed.

Instantly she felt the little hand pull free of her own and saw her daughter throw herself at the officer’s legs with the ferocity of a spitting wildcat, biting and scratching in a frenzy of rage. As if in slow motion, she watched the rifle butt start to descend toward the little head.

‘No,’ she shouted and snatched the child up into her arms before the blow could fall. But stronger hands tore the young body from her grasp.

‘No, no, no!’ she screamed. ‘She is a Danish child. She is not a Russian.’

‘She is Russian,’ the officer insisted and drew his revolver. ‘She fights like a Russian.’ Casually he placed the gun barrel at the centre of the child’s forehead.

The child froze. Only her eyes betrayed her fear. Her little mouth was clamped shut.

‘Don’t kill her, I beg you,’ Valentina pleaded. ‘Please don’t kill her. I’ll do… anything… anything. If you let her live.’

A deep groan issued from the crumpled figure of her husband at her feet.

‘Please,’ she begged softly. She undid the top button of her coat, not taking her eyes from the officer’s face. ‘Anything.’

The Bolshevik commander reached out a hand and touched her hair, her cheek, her mouth. She held her breath. Willing him to want her. And for a fleeting moment she knew she had him. But when he glanced around at his watching men, all of them lusting for her, hoping their turn would be next, he shook his head.

‘No. You are not worth it. Not even for soft kisses from your beautiful lips. No. It would cause too much trouble among my troops.’ He shrugged. ‘A shame.’ His finger tightened on the trigger.

‘Let me buy her,’ Valentina said quickly.

When he turned his head to stare at her with a frown that brought his heavy eyebrows together, she said again, ‘Let me buy her. And my husband.’

He laughed. The soldiers echoed the harsh sound of it. ‘With what?’

‘With these.’ Valentina thrust two fingers down her throat and bent over as a gush of warm bile swept up from her empty stomach. In the center of the yellow smear of liquid that spread out on the snow’s crust lay two tiny cotton packages, each no bigger than a hazelnut. At a gesture from the officer, a bearded soldier scooped them up and handed them to him. They sat, dirty and damp, in the middle of his black glove.

Valentina stepped closer. ‘Diamonds,’ she said proudly.

He scraped off the cotton wraps, eagerness in every movement, until what looked like two nuggets of sparkling ice gleamed up at him.

Valentina saw the greed in his face. ‘One to buy my daughter. The other for my husband.’

‘I can take them anyway. You have already lost them.’

‘I know.’

Suddenly he smiled. ‘Very well. We shall deal. Because I have the diamonds and because you are beautiful, you shall keep the brat.’ Lydia was thrust into Valentina’s arms and clung to her as if she would climb right inside her body.

‘And my husband,’ Valentina insisted.

‘Your husband we keep.’

‘No, no. Please God, I…’

But the horses came in force then. A solid wall of them that drove the women and old men back to the train.

Lydia screamed in Valentina’s arms, ‘Papa, Papa…,’ and tears flowed down her thin cheeks as she watched his body being dragged away.

Valentina could find no tears. Only the frozen emptiness within her, as bleak and lifeless as the wilderness that swept past outside. She sat on the foul-smelling floor of the cattle truck with her back against the slatted wall. Night was seeping in and the air was so cold it hurt to breathe, but she didn’t notice. Her head hung low and her eyes saw nothing. Around her the sound of grief filled the vacant spaces. The boy with dirty blond hair was gone, as well as the man who had been so certain the White Russian army had arrived to feed them. Women wept for the loss of their husbands and the theft of their sons and daughters, and stared with naked envy at the one child on the train.

Valentina had wrapped her coat tightly around Lydia and herself, but could feel her daughter shivering.

‘Mama,’ the girl whispered, ‘is Papa coming back?’

‘No.’

It was the twentieth time she had asked the same question, as if by continually repeating it she could make the answer change. In the gloom Valentina felt the little body shudder.

So she took her daughter’s cold face between her hands and said fiercely, ‘But we will survive, you and I. Survival is everything. ’

2

Junchow, Northern China

July 1928

The air in the marketplace tasted of mule dung. The man in the cream linen suit did not know he was being followed. That eyes watched his every move. He held a crisp white handkerchief to his nose and asked himself yet again why, in the name of all that’s holy, he had come to this godforsaken place.

Unexpectedly, the firm English line of his mouth dipped into the hint of a smile. Godforsaken it may be, but not forsaken by its own heathen gods. The lugubrious sound of huge bronze bells came drifting down from the temple to the market square and crept uninvited into his head. It reverberated there in a dull monotone that seemed to go on forever. In an effort to distract himself, he selected a piece of porcelain from one of the many stalls shouting for business and lifted it up to the light. As translucent as dragon’s breath. As fragile as the heart of a lotus flower. The bowl fitted into the curve of his palm as if it belonged there.

‘Early Ch’ing dynasty,’ he murmured with pleasure.

‘You buy?’ The Chinese stallholder in his drab grey tunic was staring at him expectantly, black eyes bright with feigned good humour. ‘You like?’

The Englishman leaned forward, careful to avoid any contact between the rough-hewn stall and his immaculate jacket. In a perfectly polite voice he asked, ‘Tell me, how is it you people manage to produce the most perfect creations on earth, at the same time as the foulest filth I have ever seen?’

He gestured with his empty hand to the crush of bodies that thronged the market square, to the sweat-soaked mule train with blocks of salt creaking in great piles on the animals’ unbreakable backs as they barged their way noisily through the crowds and past the food stalls, leaving their droppings to ripen in the grinding heat of the day. The smallpox-scarred muleteer, now that he’d arrived safely in Junchow, was grinning like a monkey, but stank like a yak. Then there was the white mess from the hundreds of bamboo birdcages. It coated the cobbles underfoot and merged with the stench of the open sewer that ran along one side of the square. Two young children with spiky black pigtails were squatting beside it, happily biting into something green and juicy. God only knew what it was. God and the flies. They swarmed over everything.

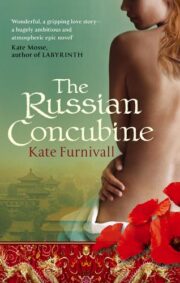

"The Russian Concubine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Russian Concubine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Russian Concubine" друзьям в соцсетях.