Soon we were sharing a jar of soup two or three times a week with Hoffmann warning me pleasantly that Herr Wolf carried a “single bed” in his heart.

Herr Wolf instructed me to poke him from time to time as we sipped the broth so that even this liquid nourishment would not be automatic and escape his concentration. This made me realize that a man can communicate something before it’s understood. And I enjoyed tickling him from time to time, watching him laugh softly against his will. As the jars of soup became larger, I realized he wanted the lunches to last longer. We would sit on the same office step for two hours. Of interest to him was what it was like for me being a young working girl, and I told him how dandelions make a good salad for lunch when you’re short of money and how I toasted bread on an upturned electric iron in back of the shop. Soon he continued on about unemployment, the shame of Germany’s poor standing in the world, his hatred of the Communist Party. He recited the Versailles Treaty by heart, grimacing over certain words, his mustache twitching after sentences. Then he’d snarl: “Clemenceau… forbidding our soldiers between the French border and a fifty kilometer line east of the Rhine! What infamy at the Hotel Majestic in Paris—that heinous delegation called the Versailles Peace Conference.” He was continually upset about the ignominy of the Fatherland in that awful War Guilt Clause which erased the former wonders of the German army and reduced it to a mere 100,000 men. (Later, I’m glad to say, he introduced compulsory military service and further flouted the Treaty by announcing on the radio that he planned to raise troop strength to 550,000.)

He encouraged me to read The Jewish State by Theodor Herzl, a book that detailed the Zionist ideal, for he was absorbed by the political Jewish problem with its territorial solution. Herzl wanted Uganda as a possible Jewish homeland, but Herr Wolf felt the use of too many German ships to get them there was not a good idea. I admitted that I personally knew only one Jew who was my mother’s cook, and she was rather dull though dutiful.

There were stories of his being a young man and feeling restless and eagerly welcoming Stahlgewitter, the thunder of the Great War. Even Thomas Mann, he said, desired a steely conflict when he wrote: “This world of peace which has now collapsed with such shattering thunder—did we not all of us have enough of it? Was it not foul with all its comfort?”

Herr Wolf said a single fear was that he would reach the front too late. This fear gave him no rest, and he eventually wrote about it in Mein Kampf. I was lucky enough to hear it from his own lips.

Later he showed me his paintings of blood-drenched poppies from the Great War.

I was honored that he used army terms when speaking to me such as “pill boxes” which were not those little pearl cases on my dresser. I would become familiar with such language. Trusting me with personal sentiments wasted on party members with jowls full of beef, he spoke of his mother, the warm home she made for him, how he would cry as a child when they entered their house because then he couldn’t see it from the outside. Before he said his first word, he drew it, a round outline of his mother’s face. The sketch called out “mutti” as loud as any word. Thereafter, he was continually horrified when anyone showed less than reverence for maternal love.

If one of his associates walked by and I was near him, he would stand, clicking his heels, shake hands with the official and then turn and shake mine. I knew I wasn’t to be part of his political life, but I didn’t care because he told me his real name was Herr Hitler. Bending nearly double, his lips would brush my palm in the old Viennese manner that embarrassed me as I didn’t even know if he was spelled with two tees or one. But he wanted me to call him Adi, the name he went by with all his closest friends. Then he pulled out a membership application form that I eagerly signed.

When the political montage was completed, he traveled around the country but promised to see me as soon as he returned saying we would go to the lake as I had told him I loved swimming. He sent me a phonograph record from Berlin. I listened to one of his speeches made on a brittle disk, expounding to his comrades about the beauty of a sparse jar of soup for lunch. I smiled in complicity as I played the record over and over until his voice grew weaker and weaker and slowly disappeared.

I began reading in the paper all about him. Nietsche’s sister said Adi was a religious rather than a political leader. Somebody named Joachim Fest was taken in by his “obscene, copulatory character at mass meetings.” (I was upset by this, but Hoffmann said it was a compliment.) Von Hindenburg called him a “Bohemian corporal.” I thought “Bohemian” was romantic.

Returning from his journey of speeches, Adi took me to Grosser Wannsee and was happy to find I was strong and muscular in the water. Too many women, he felt, were flabby and pale like the underside of a sea urchin. Explaining that I use to model swimsuits, it was annoying to me that men noticed the style and material of the suit without realizing that the firmness beneath made the swimsuit attractive. But he knew. And we went to the lake often, and he even admired my purple lips so cold from the water. After several months, now yearning for him, I picked a deserted area and decided to swim in the nude.

“I need no equipment but my skin.” I stood proudly before him naked. “A suit creates drag in the water.”

“But you wear a cap.” He smiled. His teeth were better back then, less stress.

“My hair is not cooperative.”

“You mean your hair on top?” He wasn’t looking at my head. As I stood before him, I found it strange that he had no shadow, but I came to realize he allowed nothing to escape his body without permission.

“I do wear mittens,” I explained, “to make fists for good strong strokes, so I don’t over muscle the water.” Forcing myself to do physical things excited him.

His hand strayed between my legs, and he wondered what the ligaments of my clitoris were like—how firm they must be. Such ideal German ligaments deserved a strong man.

“I can’t do any freestyle with your hand there,” I teased.

“Then water-thrash.”

“You’ll have to take off your clothes, too,” I urged. The summer air lay heavily upon my shoulders. It would be months before I realized he took his clothes off for no one, not even his doctor.

On the collar of his tunic were the Iron Cross and the black ribbon of the wounded. Slung across gnarly branches on a tree above us was the Leica II camera that started it all.

“I like to dry swim. Fully dressed. Come now, create fluid motion for me. I’ve had enough today of the robotic action of politicians, my little Evchen.”

Taking his hand from my vee, he lay on the ground, face down and struck a perfect horizontal posture, his nose slightly slanted as he breathed to the side. Then he flutter kicked—small, fast and supple. Most beginners kick too big.

“I was gassed in the Kaiser’s War.” This he said without the slightest hint of pity. “I let air gently fall into my seared lungs when inhaling. I exhale through my mouth.”

“You’re so right,” I answered happily. “Weak swimmers tend to breathe only through their nose.”

Cupping the waves, he sucked on water from the deep darkness that most people fear.

I got on the grass next to him, and he moved me expertly onto his back as we both kept our bodies long, narrow and straight—he face down, me on the top. His tusk stiffened into the sand, and then I felt a slight arch.

“My pretty Evchen, we drink from the same bowl,” he said sweetly.

“Why don’t we do it the real way?” I asked.

“What way is that?”

“You enter my soil.”

“How much more real is that?”

Wanting another aperture, he reined me in digging into the crack of my bottom with his left hand (always saving his right for handshakes). After only moments, I think he was spent. One never knew with Adi. It took a while for me to learn that he stores passion like a special solitude, a sublime way of carrying the burning sun inside himself even as he writhes from his scorching juice.

I fell in love with his middle finger.

I’ve been on many beaches from the age of six. This particular shimmering swim let my body speed through swells and surges faster than any water I had ever know before. From that day, I knew I would always love him no matter what he did to me. For Adi carries magic even when he sleeps. He doesn’t snore, and there’s a soft glow about him when he’s unconscious as he breathes in little staccato puffs of air. I lie beside him thinking: “What is he dreaming? Who has taken him away from me into that other world?” It never leaves me, this fear of being left.

2

THERE WAS NOTHING IN MY CHILDHOOD that made me believe a famous man would want me. Oh, I had the usual dreams of marrying a prince like all young girls. In Bavaria, one heard of royalty and sometimes even saw them in parades. Pages from the Court of Wittelsbach, the Bavarian royal family, were sometimes enrolled in special classes at my school. Our priest, we were told repeatedly, was once a tutor to Prince Heinrich. But the nobility kept to themselves considering people like me as the bürgerliche—poor low life. Once I forgot and greeted one of the elite in the courtyard and was punished by the nuns with a rap on my knuckles. When I told Adi this, he smiled saying he ordered Heinz, his valet, to turn his back and bow when meeting a royal.

Prince von Hessen who survived World War I joined our Nazi Party. Prince Wilhelm became a member of the SS, and Prince Philip marched with the Storm Troopers every year at Nuremberg Party rallies. At first, Adi wanted the nobility in the Party in order to show a new people’s community—Volksgemeinschaft—the bringing together of all classes of society. But he was always suspicious of the Royals because their familes were international and thus a source of information for the enemy. Eventually Adi had most of those snobs thrown into prison for treason. Rommel, to his credit, put a good deal of blame of the World War I defeat on the aristocracy saying they used their privileges to no good end. But Adi was also suspicious of Rommel, a general who was arrogant enough to reprimand his students during their War College days that they need not concern themselves with a historical Clausewitz but with him.

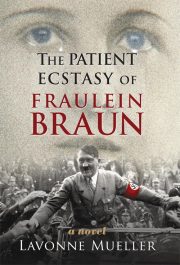

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.