“That sounds very Art deco,” I offered, proud to be able to spar with him. I took one of the empty boxes from behind the counter. One slat was gone from the side giving the appearance—if one had an imagination—of an open window. I pushed my head against the opening like a human frame and waved at him. “Now will you photograph me?”

He answered with a quizzing stare, his mustache slightly twitching upward, a mustache so perfectly even that one side was exactly the same thickness as the other side. But I could tell he was amused.

Just then Hoffmann arrived and quickly grabbed a camera to take a delightful picture. But Herr Wolf roughly snatched the camera from Hoffmann, yanked away the box that still covered my head and shouted: “I don’t allow impromptu shots.” Later, as the Führer, when he was continually photographed, he would carefully stage each and every pose and forbid any picture when he wore his reading glasses. “A photograph is a reflection with a past,” he announced preferring the colored postcards of himself painted by the famous W. Willrich.

Though his pale blue eyes were fetching, I didn’t find Herr Wolf particularly mysterious or superhuman. He seemed very ordinary except for an Austrian charm in regards to our parakeet bringing his rain cape to hang around the sides of the cage so that Albrecht wouldn’t get chilled. Telling Herr Hoffmann never to buy Albrecht a wife, he explained that a parakeet would ignore people and concentrate on his mate.

We had a fish bowl on the counter and when one of them gave birth, I delivered the baby to Hoffmann’s eight-year-old niece, Hertha, for her birthday. When Herr Wolf found out, he was angry saying it was wrong to separate a mother from her child. I had to put the baby fish back in the bowl, and poor Hertha went without a gift.

Herr Wolf would often talk to Hoffmann about Arnold Fanck who experimented with lenses, camera speeds, and film stocks. They considered him a great artist who used high-contrast images and backlighting and even went so far as to put cameras to his skis for daring downhill-racer shots. But I thought Fanck was rather silly as his pictures didn’t look normal.

For many days Herr Wolf deliberated over buying either a Minox or the new Leica II. Hoffmann talked endlessly about the importance of the Leica’s trigger operated shutter, flat range finder top, and lens with click locking apertures. One Saturday, Herr Wolf finally bought the Leica II realizing, he said, that a superior camera would free him from any prison-hours of idleness. Afterward he walked directly over to me as I was changing Albrecht’s water and said earnestly in his soft Austrian accent: “Do you enjoy watching elegant and important people?” At first I was a little annoyed because I did get to see certain famous persons who came by the shop to talk with Herr Hoffmann who himself is prominent and happens to be an outstanding photographer. And I had often attended quaint parties in Schwabing, Munich’s Latin Quarter. I like to be where the songs are sung. I didn’t consider myself a stupid country girl, even back then. But my mother always told me: “One can eat with a knife and fork and still lack gentlemanly common sense.”

Herr Wolf invited me to an event where we could see the best and finest of Munich. I knew Hoffmann regarded him highly, and I thought it might be good for business. Also, the banker I was seeing was in Hamburg visiting his sister. I hesitated but finally said “yes.” Running outside to catch a bus, Herr Wolf paused by our display window to write my name backwards in the moisture. Later, when the shop closed, he came by for me looking very ordinary in an unbelted trench coat, a black velour hat, his mustache neatly clipped. He said my name softly, his tongue sucking the sound.

On a rack in back of the shop was a maroon silk party dress with a pleated skirt, puff sleeves and a small peplum around the hips for emergencies such as this. I thought the dress might smell of printing chemicals, so I wore a fresh flower pinned at the neckline. The shop had peony bouquets on the counter. I could take a peony whenever I wanted. When I came out to meet Herr Wolf, he leaned over to smell the flower on my bodice. Having once been a painter, he was instantly drawn to the skin of a petal. Then he complimented me on the pleats in my dress saying he loves repetition in good cloth as such folds are an important part of sculptures and frescoes.

We went in a taxi speeding down Maximilianstrasse and turned off to the Don Carlos Music Café: leather chairs, dark bread soup, turnip stew, hominy pudding so rich and thick that the sauce stuck to my teeth. As we ate, I noticed him gesturing to someone behind me, lifting his head and angling it to one side in silent communication. Once he actually stood and gave a celebratory wave to whoever it was behind me. Curious and believing I would discover one of his friends, I turned around only to find a large oval mirror.

“Catching sight of a loyal friend?” I asked him coyly.

“Loyal, to be sure,” he answered followed by a careful little laugh. But he was not embarrassed, and that impressed me.

When dessert came, creamy walnut cake with pistachio ice cream, he took off his jacket and hung it over the chair, and there were delicate stains on his chest, like marks women have on their blouse when nursing. That’s when I first knew he was special. Perfume came from his nipples. (In the Bunker, it’s a great benefit for it helps us with all the acid dampness of our underworld.)

Before leaving the restaurant, he left a wildly generous tip.

“You’re going to make this place impossible for me to return to in the future,” I offered, smiling.

“So you must always come with me.”

Then he left a tip for a waiter who hadn’t even served us saying he could see pain in that waiter’s stooped shoulders.

I miss those leisurely times. When he’s busy with his generals and I ache for him, I wish he were still just an artist with only colors to capture. His tints and hues are captives, after all. If I tell him that, he scowls and says: “Pasteur could have held his own among painters. Are you sorry he chose a scientific career? Frederick the Great played the flute. Should he have been a musician?”

“Perhaps their wives would have wished it,” I say.

He hesitates for a brief moment, then goes on to talk as if he had not heard me. “Now El Greco should have painted houses. His faces are dumb and who wants to talk to them.”

“I’ve never seen any Greco. But I admire poor Monet who went blind and had to memorize where he put the colors on his palette.” I’m grateful to Sister Angelus in my convent school who had cataracts and spoke frequently about the painter.

He suddenly closes his eyes, in respect and sadness, remembering that time in the Great War when he temporarily lost his sight. Patting my hand, he thanks me for my sensitivity.

But I’m happy that our Führer tells painters in Germany not to use any tint that can’t be seen in nature by the naked eye and not to paint or draw repellent or revolting images. He ordered the Gestapo to conduct raids on artists to examine their brushes for forbidden colors.

But getting back to our first outing… we walked up the steps to this new hospital on Ludendorffstrasse. He stopped and squinted when he saw a lone biscuit wrapper on the stairs, picking it up and placing it firmly in a nearby trash container. Soon we stood in front of ugly steel doors with a thick red ribbon stretched across them. Funny little stick figures (that I later knew as swastikas) were stitched on a banner quivering in the breeze. People were packed together waiting, I didn’t know for what. We were ushered to a row of wooden chairs. Looking around, I didn’t see any cinema stars but just some shabbily dressed politicians and a few doctors and nurses in ugly unstarched uniforms. I was annoyed that I had come and ruined a good evening. More and more people arrived, and large six-wheeled black Mercedes with red leather upholstery screeched up, but there were no film stars that I could see, and I was getting more and more bored when suddenly… he just left me—all alone, sitting there! Left my side without a word! Had he run out on me? The next thing I knew, he was up front receiving a bouquet from a little girl, cupping the child’s face in his hands, smiling, then cutting the thick strip of red satin ribbon to officially open the new hospital. Doves were released in the air, and an orchestra that came out of nowhere played Wagner’s “March of homage.”

Little did I know that on the very street of this hospital, he had once shoveled snow for a few pfennigs when he was poor and a struggling artist. More amazing, one day those swastikas I didn’t even know the name of would fly over the Ritz in Paris.

After the opening of the hospital, he didn’t come by the shop or call me in over two weeks. I wondered if I had only been a last minute replacement as he had invited me just hours before the event and didn’t even so much as pat my cheek when the evening was over. Then… he suddenly appeared carrying a box of film for Herr Hoffmann to arrange in an elaborate political montage. Hoffmann gave him a warm “sieg heil,” something new to me. (I didn’t know that Hoffmann joined his party early with the number 59.)

“Think of it,” Hoffmann told me, “he’s an Austrian, a born politician who only recently became a German citizen. And he’s going to make Germany great. We need a genius of action—Taterperson, this shaker. Tater.”

As he used the store phone, I overheard Herr Wolf’s conversations in which he made arrangements for speaking engagements at various cities. Afterward, he casually asked me to lunch. I accepted eagerly remembering all the doves and music of our first extravagant encounter. But this time, we only walked across the black asphalt street, dodging the traffic as he told me that most of his friends dreamed of owning their own Leica, but his dream was to be the camera itself. We sat on the steps of an office building. He carried a bottle of tepid tomato soup in a brown paper bag, and we took turns drinking from it. Eating too much at lunch was bad for one’s productivity, he explained. Most of his party members wanted heaping plates of meat, something hard for him to witness. I took numerous sips, and he drank the last of it and finished by running his tongue slowly around the upturned rim so that I saw the jar’s murky bottom. He used to drink soup from the same bowl with his mother, he said.

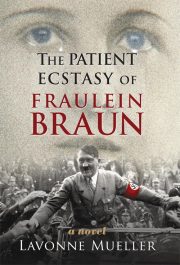

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.