My family is not stylish—just simple and honest. My mother, an ardent Catholic who displays her faith wearing a large red scapula, is a dressmaker who uses pillow feathers in her hat. My father is a teacher of crafts who has little interest in students and considerable interest in the principles of construction. As a child, my building blocks were discarded wood.

I was born on a rainy day and our roof leaked so the midwife delivered me wearing a rain hat and rubber boots. One hand came out first, and perhaps at that moment I was already reaching for Adi.

My sisters Ilse, Gretl, and I grew up in a small house with a wide yard, and we walked between rows of sunflowers taller than we were and went to a Catholic school and waited on the street corner to meet the nuns and carry their satchels. We were always told in our classes that we should be proud of Germany’s great art and literature. An deutschem Wesen soll die Welt genesen. The German spirit will heal the world. Any mention of imperial places like France or Spain would deform our character.

I was good in reading, poor in math, very athletic and was always chosen to be the leader of our exercises that we performed before church each morning.

So my life before Adi was very ordinary. But I wish those haughty Bavarian nobility could see me now.

3

THIS BUNKER IS MY FIRST REAL HOME. Like a ship, you’re born when you enter it. Here is my world of eighteen rooms where clammy air rises like part of the starkness of concrete.

Generals, officers, clerical staff acknowledge me. Before, I was hidden. Nobody was supposed to see me. Nobody was supposed to hear me. I was the secret woman.

In this Bunker, we’re staying put at last. In a sense, nesting. There’s bicycles sprawled along the floor and military furniture, horse blankets, field glasses, bull castration tongs, mess kits, tire rods, crowbars for me to contend with. I think of the Bunker as Michelangelo’s block of marble that can be turned into something wonderful even though Adi is against it. A bunker is a bunker. Probably it reflects his background as a corporal in World War I. Having seen conflict from the trenches, he’s down to earth. You don’t have to be born rich to get ahead. You can be a peasant and become a general at twenty-four and rule France at thirty. Little Bonaparte proved the common individual was able to triumph. I’m proud of Adi’s humble origins, but I worry, too, because now that the Allies have reached Berlin, they’ll shoot any corporal they find to make sure there’s never another Führer. Oh, I can’t let myself think about the bleak side of things. Not when ingredients for cakes are carefully saved in a tin box for Adi. They are modest cakes, but our cook, Fräulein Manzialy, who wears a swastika badge on her apron, has found just enough yogurt for icing. Adi’s favorite jellied pancakes are skillfully cooked in the shape of Napoleon’s hat. Yogurt is still unrationed and the beer supply is scarce even when it’s watered down though Adi never touches the stuff, and I only have a half bottle of schnapps now and then. Goebbels, our Propaganda Minister, found a raspberry liqueur that he and Magda drink each night before dinner with cakes in the Greek manner, and his First Adjutant, Lieutenant Wisch, (who wears the Medal of Blood from the beer hall putsch) brings them bottles of Juniper wine in hand painted bottles along with Eiercognac, and Samagonka (a Russian brandy made from beets). From Lieutenant Wisch (who is short and wiry and once was a jockey) we also get plenty of sugar and cheese. Lieutenant Wisch has five Opel Blitz trucks at his command and makes weekly runs to many of the big cities where he is liked by everyone and got to sign his name in the Golden Book of the city of Bonn even though he was born in Schuchten bei Treuberg.

Entering this stout old Bunker, Magda says, is like putting on a drab turtle’s shell. But after finding herself close to so many handsome soldiers, the turtle’s shell is more appealing. She moved a special end-table from her country home to the Bunker—a tiger-oak table with four naked men for legs, their genitals moving fuzzily into a complex of circles and cubes. When I complained it was unsightly, Magda huffed that furniture is the only way to “flower” the Bunker. When Adi accidentally toppled over this end-table breaking off a scrotum, Magda treasured it even more saying proudly to everyone that it was “broken by the Führer.”

I’m grateful for what we have in this damp shelter that groans and laughs depending on slurry bombs. There’s a little too much battleship gray and stark concrete for my taste. But many have less. Fräulein Manzialy never has the onions we crave for onions are used to make poison gas. But what can you do? It’s war. However, she mixes fried potato drippings to day old bread pudding, a succulent combination that leaves our lips moist and glistening.

Staying up late and watching for the first light used to be fun. Maybe it had rained and I could see blue lightning in the sky. Each morning I loved to watch Adi stand before his open window and do chest-expanding exercises that helped keep his right arm rigid for hours with the Nazi salute. But he’s given that up in the Bunker because he hardly salutes any more, and morning and night mean nothing. Every hour is like the last. That sameness leaves me time to realize how special it is to be here, how happy I am to finally be “visible.”

My first day in the Bunker, Adi didn’t come to my room that night as he was working straight through with Bormann, his adjutant, and Goebbels, his propaganda minister. He doesn’t go to bed until early in the morning and only sleeps a few hours, a habit he acquired as a messenger in the army. What little sleep he does get he fights as that awful thief of time. I was disappointed but too excited to be unhappy for long. My first night in our first home! Spreading an army blanket on the floor and leaving my pillow on the bed, I wanted to feel like a corporal on the front, one of Adi’s loyal soldiers. Wasn’t I at the nerve center of the most important command post in the world, in a place I was never allowed to be before, living among soldiers smelling of mud and sweat? Stretching long and straight on the blanket, I let my hands trail on the floor so I could feel the cold. I wouldn’t let myself go to sleep, even for a moment—not for the entire night. Shivering from intoxication, I whispered strange sounds, not out of fear but because of the restlessness you have in a new place. I didn’t use a blanket for I knew that would dull my bliss. I was throbbing with bursts of delight, as a shutter breathes on a window vibrating against the frame when there’s a delicious breeze. My eyes closed from time to time, content in the bowels of time, concrete around me like the Bunker’s own dream.

From the start, I keep my door slightly open during the day to hear life rushing by: gold-tasseled swords at a soldier’s side banging against stiff black boots, strutting captains, majors, and generals all working intimately with history. The bombs above slacken, then come hard rattling the lids on pots and pans, then slacken again. Sometimes a touchy guard at the top heaves a grenade outside the entrance at an imagined enemy. Life moves above, but this life swirling beside my room is a lofty heaven underneath. There’s no war, I decided that first night as I shook with rapture and anticipation, that’s too big or too destructive it can’t be held inside me.

A few feet away from me is Adi’s private apartment with sealed double doors that are gas proof and fireproof with an inner connecting door to my room. By his bed is a scale as he worries about his weight. To give himself the best advantage, he quickly exhales before weighing himself.

I’m happy when secret war talks with Goebbels are held in Adi’s private apartment. Sound carries easily in concrete rooms, and I can hear my love clear his throat or cough and feel him near.

My boudoir is pleasant with a flame-mahogany old sewing machine cabinet for a desk and a charred lampshade that I’ve painted blue and white, the colors of Bavaria where Adi had his first great political success. Draped around my mirror—which I dust with face powder to smooth my reflection—is a slightly tattered red velvet cloth and a scarf with the pink flamingo. My dressing table, a thick board over two ammunition boxes, is where I keep my ivory comb and brush that Adi gave me on my birthday after we’d been together for one year. For my next birthday, he gave me a twin lens Rolleiflex with shutter speed up to 1⁄500 of a second and trusted me to take private pictures of him at Berchtesgaden for our own personal album. But I must admit I’ve never felt much joy in celebrating my birthday. After meeting Adi my real birth is the day he came into my life.

I found an iron urn and had a captain with a twisted moustache like some old Kaiser and who smelled of a long night of drinking sand it with grit and paint it with copper crystals. It’s very Grecian and perfect for fruit and driftwood. I’m thankful for learning my mother’s thrifty Bavarian sense for ersatz.

B-B is the Blondi Bunker, wasted space for a mutt. The DogBunker would make a perfect tearoom. But Adi won’t hear of it. When I ask him why not, he tells me the same old story about Napoleon. During the Italian campaign, Napoleon saw a dog on the battlefield coming from his dead master howling, barking for help, growling revenge. Nothing moved the little Emperor more, and nothing moves Adi more except maybe when Nietzsche wept and put his arms around a horse being beaten.

The lower part of our shelter is called the Führerbunker—above, the old bunker. At the end of the hall is the telephone switchboard, the best in Berlin. We also have an army radio transmitter with a hidden outside aerial. Rumored to have gold bars buried in the floor, Adi’s Party Secretary, Bormann, has the smallest room without even one tiny shelf for books. Bormann, known as the “Grey eminence” because he likes to remain in the background, never reads a book or holds one in his hand except the Army Register. As a schoolboy, he would prop up a book on his desk and eat chocolates behind it. The teachers thought he was scholarly. But that doesn’t keep him from making Adi believe that he’s read Mein Kampf. They all say they’ve read Kampf though my mother says nobody gets beyond 20 pages. Everyone honors it, of course. And even when I ask Adi’s valet, Heinz, if he’s read Kampf, he only says: “The Führer’s words are a bit difficult for me.” But I’ve read it. Every page. When Adi is with me, he needs to relax so I try not to ask him too many questions though he’s happy I’m interested and knowledgeable about the war and pleased that I send copies of Kampf as gifts to my friends and relatives. And as a wedding gift, Adi mandates a copy to all newly married couples in the Reich. My mother says Kampf is so dense it reads like old wood. What would she know having spent her whole life sewing and cooking red sauerkraut in heavy raisin gravy? There are no earth shaking words in wool-scraps or gravy.

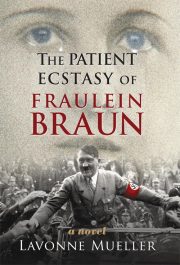

"The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Patient Ecstasy of Fräulein Braun" друзьям в соцсетях.