Her brain was crawling with might-have-beens, as irritating as lice in one’s scalp—crawling, biting, itching, impossible to claw out. If only she had kept closer watch on Pierre-André; if only she had jumped off the stage and tackled Delaroche when first she spotted him; if only she had told André who and what she was rather than waiting to let him find it out at the worst possible time from the worst possible person.

It wasn’t my secret to tell, she defended herself to an invisible André. It wasn’t anything to do with you.

That was another thing. It wasn’t as though André had confided in her out of choice. It was circumstance on his side, not moral high ground. If Daubier hadn’t been discovered, they would have gone on just as they were, she playing the governess, André playing his double game, neither the wiser.

Of course, then, they hadn’t been sharing a bed.

Laura stared at her own reflection in the glass of the bookshelves and wondered, resentfully, why that was meant to change anything. Whores gave their bodies to multiple men multiple times a day—or so she had been told. Did that mean they were meant to give their trust where they gave their bodies? Did giving one’s body necessarily mean giving of oneself?

Everything for love, that had been her mother’s motto. Nothing held back, nothing denied. All body, all soul, all mind, all heart.

That wasn’t love; it was willful self-destruction.

That, her mother would have claimed, was love. To fling oneself on the pyre of passion, rising phoenix-like from the ashes—scoured, purified, reborn.

But what if one doesn’t rise again? Laura had argued, sixteen years old and stubborn. What if one simply burns?

Her mother had no answer for her. Neither did her shadow image in the bookshelf.

Laura turned away from the glass. It was terrifying, this notion of tearing chunks off one’s soul and handing them over to another for safekeeping. It had been easier not to tell André the truth, to keep her own counsel the way one might keep a packed portmanteau, always ready to pick up and move on at a moment’s notice, settling nowhere, trusting no one.

If one never got attached, one never got hurt.

Next to her, Gabrielle sat curled up in a wide-armed chair, reading. As Laura paced past, Gabrielle glanced up from her book.

“What time is it?”

Laura consulted the watch pinned to her breast. “Five past eleven.”

Gabrielle nodded and went back to her book—Laura peeked sideways at the lettering on the spine—Voltaire’s Candide. All for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

It was twenty minutes now since André had left with Lord Richard and Daubier. Only twenty minutes. It felt like months.

Laura’s skirt dragged against her legs as she paced. She kicked it out of the way. She was still dressed as Ruffiana, although bits of her costume had gone missing along the way. Her cap was somewhere backstage, her petticoats discarded. Without them, her skirts hung too long, despite her attempts to kirtle them up. The stomacher pressed uncomfortably against her ribs, heavy with embroidery, thick enough to repel a bullet.

Perhaps she ought to have offered the stomacher to André, presented it to him as armor. The doublet he wore as Il Capitano was a flimsy thing, the shoddiest of secondhand silks.

Laura wished Lord Richard had let her go with them. She might not have extensive combat training, but she could point a pistol and pull the trigger, or use the proper end of a pointy bit of steel if it came down to it. Yes, yes, she knew there were refinements to such things, but she doubted Delaroche’s men were going to be judging her on the niceties of her fencing, and when it came down to it, an extra pair of arms was an extra pair of arms.

Five against however many Delaroche might have mustered wasn’t exactly good odds, especially when it was such a five. For all his determination, André’s chosen weapon was the pen rather than the sword. He was a petit bourgeois, not a gentleman born. Fencing and marksmanship were a gentleman’s occupations, not the province of a provincial lawyer. Then there was Daubier, who couldn’t even wield his brush anymore, much less a sword. They were five, against goodness only knew how many, with only one real swordsman in the lot of them.

“You’ll wear a hole in the carpet,” de Berry said lazily, nearly tripping her as he kicked out his heels in front of her. “Do sit down, Miss Grey.” And then, with what Laura recognized as royal condescension, “Care for a hand of cards?”

“No,” said Laura shortly. “Thank you. Your Highness.”

Gabrielle looked up from her book. “What time is it?”

“Must you keep asking?” Laura snapped, and instantly regretted it. “I’m sorry. I’m just a bit . . . on edge. They’ll get Pierre-André back, you know. Lord Richard is an expert at this sort of thing.”

Lord Richard had been an expert at this sort of thing. He had been retired for more than a year now, running a training camp in Sussex. To teach and to do were two different things. No one knew that better than Laura. What if his skills had grown rusty with disuse? What if he had miscalculated?

“They’ll be back before we know it,” said Laura, too loudly.

Gabrielle closed her book over one finger, the instinctive gesture of the perpetual reader. Her brows came down over her nose, making her look very like her father. Her eyes were that same peculiar shade of bright blue.

“What happens if they don’t come back?” Gabrielle did her best to keep her voice nonchalant, but there was a bit of a wobble in it.

Laura looked at Gabrielle, really looked at her for the first time in days. From the paintings, she had been a pretty baby and would likely be an attractive woman someday, but she wasn’t a prepossessing child. Her face was too round and her brows were too thick and her hair had frizzed in the rain. Her shoulders were hunched, her expression guarded.

It wasn’t just her father Gabrielle had to worry about; it was her whole world, the only people left to her. Her father, her brother, Jeannette, even Daubier—all of them were in Delaroche’s power.

“If they don’t come back, you’ll have to come to England with me,” Laura said levelly. “I know I’m not your first choice, but we’ll muddle along somehow. You won’t be left to fend for yourself.”

Nine was too young for that. Sixteen had been too young for that.

Before either could say anything else, there was the sound of heavy footfalls on deck.

Gabrielle dropped her book and scrambled out of her chair. “They’re back!”

“It’s too soon—,” Laura began, but Gabrielle was already at the door, wrenching it open.

There was a man in the doorway, but it wasn’t the right one. He wore a rusty black coat and a hat too high to fit through the door frame.

He doffed it at the sight of Gabrielle. “Mademoiselle Jaouen. We meet again.”

Gabrielle instinctively tried to close the door, but she was too slow. Delaroche caught it on the point of what Laura very strongly suspected was a sword cane. “I wouldn’t do that if I were you, Mademoiselle Jaouen,” he said, sounding as though he rather hoped she might try. “Terrible things happen to those who attempt to thwart the will of Gaston Delaroche.”

The deck of the Bien-Aimée was deserted as the overburdened dinghy drew up alongside. There was no sign of the men Lord Richard had left on board. The lanterns that had been burning on deck before had been either shuttered or extinguished.

There was, however, a boat attached to the stern that hadn’t been there before.

“This is not good,” murmured Lord Richard.

André didn’t need to voice the words. He felt them in his bones. He looked at Pierre-André curled up on Jeannette’s lap, and felt a surge of terror for Gabrielle.

At least she had Laura with her. Laura was resourceful. Laura would—

Laura wasn’t Laura.

André nodded to Lord Richard. “Look. Over there. In the cabin.”

The rest of the boat was dark, but the cabin was still brightly lit. Through the window, André could see a man in a dark coat elbowing his way into the room, closely followed by several others. It was hard from that angle to see how many there were. The general impression was that there were a lot. Delaroche was taking no chances.

“He has all his men in there,” said Lord Richard with professional disapproval. “That’s just poor tactics.”

“Or good sense,” countered André. “He can pick us off one by one as we try to get through the door. We have to find another way.”

Or not. The boat rocked as André leaned instinctively forward. Delaroche’s henchmen had their guns pointed on his daughter. Oh, to be able to fly. He was too far away to get to her in time, too far away to do anything.

As he watched, useless, Laura grabbed Gabrielle, using her own body as a shield between his daughter and Delaroche.

Lord Richard looked thoughtful. “Unless we go through the window . . .”

They’d wasted enough time. “Good enough,” said André, grabbing the rope on the side of the ship. “Jeannette and Pierre-André, you stay in the dinghy until we give the all-clear. Daubier and I will take the door; you, Stiles and Pete take the window. We’ll catch them in a pincer.”

“Jaouen?” André looked back down. His old adversary, the Purple Gentian, raised a hand to him in salute. “Good luck.”

Delaroche hadn’t come alone.

There were men behind him, four of them, all of the large and hulking variety. All were holding pistols. And they were trained on the little girl in the doorway.

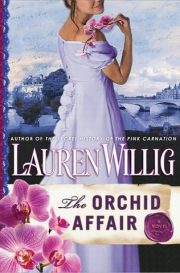

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.