“Drop it!” she said in her best governess voice, and followed it up with a feint to the chest.

Jean-Marc dropped his gun.

Daubier scooped it up in his left hand and pointed it at Delaroche. “Call them off,” he growled, in a voice André had never heard him use before. “Call off your men.”

Delaroche was known for many things, but common sense wasn’t one of them. He backed away, glass crunching under his boots. “You can’t shoot that,” he sneered. “Not with one hand.”

“Can’t I?” said Daubier, and pulled the trigger.

Chapter 34

Daubier missed.

The bullet went wild, hitting the glass front of Lord Richard’s bookshelf instead, sending bits of glass and chips of cherrywood flying. Delaroche dropped to the ground, shielding his face with his hands.

Laura lunged forward, grazing Delaroche’s wrist. More alarmed than hurt, he toppled back, landing flat on his derriere, his legs splayed out in front of him. Laura seized the advantage of his momentary confusion to level the point of the sword at his throat, just at the vulnerable spot between his cravat and his chin.

“My point,” she said levelly. “Call off your guards.”

Delaroche’s guards were milling confusedly, except, of course, for the one crouched against the wall, bleeding from his nose.

“Hold!” André’s voice rang out—the sort of voice one could imagine commanding the attention of an entire assembly—perfectly pitched, resonant with authority. Laura risked a peek. He was standing with one arm around Gabrielle’s shoulder, the other holding the bleeding guard’s pistol. “You’re outnumbered. Drop your weapons.”

“Don’t!” squeaked Delaroche, and scooted back on his behind as the sword grazed his neck.

André looked around at the assembled guards. “Has Monsieur Delaroche paid you? Anything?”

They dropped their weapons.

“I thought so,” said André.

Laura held the sword cane steady at Delaroche’s throat. “Have no illusions,” she said. “I have no qualms about using this.”

“I do,” said Lord Richard, coming up behind her, “but only because there are some chaps in London who have a number of questions they would be delighted to put to Monsieur Delaroche.”

“You are too generous, Monsieur,” said Daubier.

“Oh no,” replied the Purple Gentian with a smile that wasn’t quite a smile at all. “I don’t think so. Monsieur Delaroche, of all people, should know what it is to be put to the question.”

Delaroche went very, very still.

Lord Richard nodded at Delaroche. “Tie him. As for you lot,” he said to the guards as Laura got busy with the curtain cords. “I offer you safe conduct back to shore. You will forget you were here tonight.”

“To help you forget,” added André, “how about a few carafes of wine?”

Delaroche’s henchmen seemed to feel that this was, indeed, a fair deal, although they seemed inclined to haggle over the exact number of carafes involved.

“Ouch!” One suddenly leaped aside, both hands clasped to his posterior.

“Hmph,” said Jeannette, sheathing her knitting needle in a skein of wool. “If you had simply moved when I had asked, I wouldn’t have had to do that.”

“Safe conduct, you said?” said Jean-Marc—at least, Laura thought it was Jean-Marc. She had a great deal of trouble telling them apart. He backed away from Jeannette. “We’ll take that safe conduct now if it isn’t too much trouble, sir.”

Amazing what the application of a knitting needle could do for one’s manners. Laura would have to remember that for the next time she taught deportment.

Only—she caught herself up short—she wasn’t teaching deportment. She wasn’t a governess anymore. She wasn’t sure what she was, or even who she was.

“An excellent mission, Miss Grey,” the Purple Gentian told her, clapping her on the shoulder in passing. “Well done, nabbing Delaroche! The powers that be will be pleased.”

Laura couldn’t help it. She looked at André and saw his head jerk at that Miss Grey. Their eyes met for a moment. He had lost his spectacles somewhere on the other boat, and his eyes looked naked and lost without them. She’d always had the uncanny sense that he was looking through her, seeing through to the things she most wanted to keep hidden. Why, then, now that it mattered, did it feel like he wasn’t seeing anything at all?

Don’t hate me, she wanted to say, but she couldn’t somehow.

Pierre-André made a run around Jeannette, shouting, “Papa!”

André’s attention abruptly shifted. He leaned down to hug his son, who flung himself, in his signature fashion, at André’s waist.

Laura stepped back, knowing herself to be irrelevant. This past month, after all, had been nothing more than fantasy, a play they played offstage as well as on. She had no place in the family circle.

“Pierre-André!” Gabrielle, for one, was delighted to see her little brother. Abandoning her father, she hugged him until he squirmed.

“Can I have a parrot?” asked Pierre-André.

They sent Delaroche’s guards back to shore with cards affixed to their necks bearing the image of a small, purple flower. For old time’s sake, the Purple Gentian had said, and since it was his ship, it seemed ungrateful not to let him have his way.

Delaroche they kept on board, well-trussed. Jeannette had insisted on retying him, deeming Laura’s ad hoc measures insufficiently thorough. All those years of knitting had given her a masterful way with knots. For once, she and Daubier had been in perfect accord.

Gabrielle and Pierre-André had been happily reunited with each other and their father. There was much hugging and exclaiming and general rejoicing while the stuffed parrot looked benevolently on. Pierre-André was much taken with the stuffed parrot. He was already practicing his “avast, me hearty,” slightly hindered by his inability to pronounce aspirates.

André apologized to the Purple Gentian for the ruin of his cabin and the Purple Gentian blandly assured him that it had been due for redecoration anyway.

In short, an excellent time was being had by all.

Among all the merriment, one former-governess-turned-spy wasn’t likely to be very much missed. Laura made her way to the back of the ship—she was sure there was a name for it, but things nautical had never been much to her taste, for obvious reasons—and watched France recede in the wake of the boat until the lights of the harbor were little more than an echo on the water, and then nothing at all.

An excellent mission, the Purple Gentian had told her. She had rescued the Duc de Berry and captured a high-ranking, if slightly insane, French operative. She ought to be basking in her triumph.

Instead, she just felt tired. Tired and oddly let down. The thought of going back to England, to the boxes in the basement of Selwick Hall, to her old life as Laura Grey, or even her new life as the Silver Orchid, depressed her.

She found herself wishing, insanely, that she could turn back the clock by a week. She wanted to be back in the Commedia dell’Aruzzio. Absurd. She’d hated the Commedia dell’Aruzzio. She’d hated acting; she hadn’t much liked the other actors; and she certainly hadn’t been a fan of sleeping in fields and washing in lakes—washing, that was, when one had the chance to wash at all. She hadn’t liked the rowdy audiences or, even worse, the sulky and silent ones. She hadn’t liked the mules that had pulled the wagon or the ruts that seemed to be a perpetual feature of French country roads in early spring.

But there it was. She wanted to be back in that dreadful, drafty, creaky wagon where the roof leaked when it rained and the bed wasn’t quite large enough for two. She wanted to be on the damp ground by a smoky campfire with burnt stew if it meant that there would be an arm around her shoulders and a familiar voice murmuring things not meant for the rest of the company into her ear. She wanted to go back to being not Miss Grey or Mlle. Griscogne, but Laura of no surname at all.

She wanted to be with André.

Her mother had been wrong. Love wasn’t a grand explosion. It didn’t blaze onto the scene like a comet; it crept in like a spy in the night, muffled and disguised, worming its way in, not revealing itself until it was too late to do anything about it. Love didn’t attack; it infiltrated. The poets had gotten it wrong. Laura held them all personally accountable.

There were quiet footfalls on the deck behind her. Laura didn’t need to turn around to know who it was. She knew his tread by now, the same way she knew the way his hair smelled after three days on the road, the different tones of his voice, his trick of pulling off his spectacles with one hand.

“You ran off,” he said.

Laura didn’t turn. She didn’t want to look at him. She’d prefer to remember him as they had been before, not as he had looked when Lord Richard had uttered that first Miss Grey. Shouldn’t she be allowed to keep just one little memory intact, like a pressed flower in a book?

Pressed flowers were, by their nature, dead. Laura grimaced at the thought. So much for sentimentality.

Without looking at André, Laura said, “I lied to you.”

She could feel the weight of him settling on the rail beside her. “I know,” he said equably. “I lied to you, too.”

Laura kept her eyes on her hands, determined to make a clean breast of it. “My real name is Laura Griscogne. For the past sixteen years I’ve been Laura Grey. The Pink Carnation recruited me last summer.”

She had thought he would ask about the Pink Carnation, about her work. He didn’t. “Your parents?”

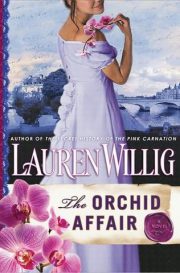

"The Orchid Affair" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Orchid Affair". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Orchid Affair" друзьям в соцсетях.