I check myself. They were wrong, my mother and father. Finally, I say the unsayable, unthinkable thing. They were wrong, my mother and father. Soldiers of genius they may have been, convinced they certainly were, Christian kings they were called—but they were wrong. It has taken me all my life to learn this.

A state of constant warfare is a two-edged sword: it cuts both the victor and the defeated. If we pursue the Scots now, we will triumph, we can lay the country waste, we can destroy them for generations to come. But all that grows on waste are rats and pestilence. They would recover in time, they would come against us. Their children would come against my children and the savage battle would have to be fought all over again. Hatred breeds hatred. My mother and father drove the Moors overseas, but everyone knows that by doing so they won only one battle in a war that will never cease until Christians and Muslims are prepared to live side by side in peace and harmony. Isabella and Ferdinand hammered the Moors, but their children and their children’s children will face the jihad in reply to the crusade. War does not answer war, war does not finish war. The only ending is peace.

“Get me a fresh messenger,” Katherine said over her shoulder, and waited till the man came. “You are to go to my lord Surrey and tell him I give him thanks for this great news of a wonderful victory. You are to tell him that he is to let the Scots soldiers surrender their arms and they are to go in peace. I myself will write to the Scots queen and promise her peace if she will be our good sister and good neighbor. We are victorious, we shall be gracious. We shall make this victory a lasting peace, not a passing battle and an excuse for savagery.”

The man bowed and left. Katherine turned to the soldier. “Go and get yourself some food,” she said. “You can tell everyone that we have won a great battle and that we shall go back to our homes knowing that we can live at peace.”

She went to her little table and drew her writing box towards her. The ink was corked in a tiny glass bottle, the quill especially cut down to fit the small case. The paper and sealing wax were to hand. Katherine drew a sheet of paper towards her, and paused. She wrote a greeting to her husband; she told him she was sending him the coat of the dead Scots king.

In this, Your Grace shall see how I can keep my promise, sending you for your banners a king’s coat. I thought to send himself to you, but our Englishmen’s hearts would not suffer it.

I pause. With this great victory I can go back to London, rest and prepare for the birth of the child that I am sure I am carrying. I want to tell Henry that I am once again with child; but I want to write to him alone. This letter—like every letter between us—will be half public. He never opens his own letters, he always gets a clerk to open them and read them for him, he rarely writes his own replies. Then I remember that I told him that if Our Lady ever blessed me with a child again I would go at once to her shrine at Walsingham to give thanks. If he remembers this, it can serve as our code. Anyone can read it to him but he will know what I mean—I shall have told him the secret, that we will have a child, that we may have a son. I smile and start to write, knowing that he will understand what I mean, knowing what joy this letter will bring him.

I make an end, praying God to send you home shortly, for without no joy can here be accomplished, and for the same I pray, and now go to Our Lady at Walsingham, that I promised so long ago to see.

Your humble wife and true servant,

Katherine.

Walsingham,

Autumn 1513

Katherine was on her knees at the shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, her eyes fixed on the smiling statue of the Mother of Christ, but seeing nothing.

Beloved, beloved, I have done it. I sent the coat of the Scots king to Henry and I made sure to emphasize that it is his victory, not mine. But it is yours. It is yours because when I came to you and to your country, my mind filled with fears about the Moors, it was you who taught me that the danger here was the Scots. Then life taught me a harder lesson, beloved: it is better to forgive an enemy than destroy him. If we had Moorish physicians, astronomers, mathematicians in this country we would be the better for it. The time may come when we also need the courage and the skills of the Scots. Perhaps my offer of peace will mean that they will forgive us for the Battle of Flodden.

I have everything I ever wanted—except you. I have won a victory for this kingdom that will keep it safe for a generation. I have conceived a child and I feel certain that this baby will live. If he is a boy I shall call him Arthur for you. If she is a girl, I shall call her Mary. I am Queen of England, I have the love of the people and Henry will make a good husband and a good man.

I sit back on my heels and close my eyes so the tears should not run down my cheeks. “The only thing I lack is you, beloved. Always you. Always you.”

“Your Grace, are you unwell?” The quiet voice of the nun recalls me and I open my eyes. My legs are stiff from kneeling so long. “We did not want to disturb you, but it has been some hours.”

“Oh, yes,” I say. I try to smile at her. “I shall come in a moment. Leave me now.”

I turn back to my dream of Arthur but he is gone. “Wait for me in the garden,” I whisper. “I will come to you. I will come one day soon. In the garden, when my work here is done.”

Blackfriars Hall

THE PAPAL LEGATE SITTING AS A COURT TO HEAR THE KING’S GREAT MATTER, JUNE 1529

Words have weight. Something once said cannot be unsaid, meaning is like a stone dropped into a pool; the ripples will spread and you cannot know what bank they wash against.

I once said, “I love you, I will love you forever,” to a young man in the night. I once said, “I promise.” That promise, made twenty-seven years ago to satisfy a dying boy, to fulfill the will of God, to satisfy my mother and—to tell truth—my own ambition, that word comes back to me like ripples washing to the rim of a marble basin and then eddying back again to the center.

I knew I would have to answer for my lies before God. I never thought that I would have to answer to the world. I never thought that the world could interrogate me for something that I had promised for love, something whispered in secret. And so, in my pride, I never have answered for it. Instead, I held to it.

And so, I believe, would any woman in my position.

Henry’s new lover, Elizabeth Boleyn’s girl, my maid-in-waiting, turns out to be the one that I knew I had to fear: the one who has an ambition that is even greater than mine. Indeed, she is even more greedy than the king. She has an ambition greater than any I have ever seen before in a man or a woman. She does not desire Henry as a man—I have seen his lovers come and go and I have learned to read them like an easy storybook. This one desires not my husband, but my throne. She has had much work to find her way to it, but she is persistent and determined. I think I knew, from the moment that she had his ear, his secrets, and his confidence, that in time, she would find her way—like a weasel smelling blood through a coney warren—to my lie. And when she found it, she would feast on it.

The usher calls out, “Katherine of Aragon, Queen of England, come into court”; and there is a token silence, for they expect no answer. There are no lawyers waiting to help me there, I have prepared no defense. I have made it clear that I do not recognize the court. They expect to go on without me. Indeed, the usher is just about to call the next witness…

But I answer.

My men throw open the double doors of the hall that I know so well and I walk in, my head up, as fearless as I have been all my life. The regal canopy is in gold, over at the far end of the hall with my husband, my false, lying, betraying, unfaithful husband in his ill-fitting crown on his throne sitting beneath it.

On a stage below him are the two cardinals, also canopied with cloth of gold, seated in golden chairs with golden cushions. That betraying slave Wolsey, red-faced in his red cardinal’s robe, failing to meet my eye, as well he might; and that false friend Campeggio. Their three faces, the king and his two procurers, are mirrors of utter dismay.

They thought they had so distressed and confused me, separated me from my friends and destroyed me, that I would not come. They thought I would sink into despair like my mother, or into madness like my sister. They are gambling on the fact that they have frightened me and threatened me and taken my child from me and done everything they can do to break my heart. They never dreamed that I have the courage to stalk in before them, and stand before them, shaking with righteousness, to face them all.

Fools, they forget who I am. They are advised by that Boleyn girl who has never seen me in armor, driven on by her who never knew my mother, did not know my father. She knows me as Katherine, the old Queen of England, devout, plump, dull. She has no idea that inside, I am still Catalina, the young Infanta of Spain. I am a princess born and trained to fight. I am a woman who has fought for every single thing I hold, and I will fight, and I will hold, and I will win.

They did not foresee what I would do to protect myself and my daughter’s inheritance. She is Mary, my Mary, named by Arthur: my beloved daughter, Mary. Would I let her be put aside for some bastard got on a Boleyn?

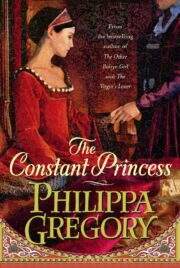

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.