Messengers passed constantly between Katherine’s army and the force commanded by Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey. Their plan was that Surrey should engage with the Scots at the first chance, anything to stop their rapid and destructive advance southwards. If Surrey were defeated, then the Scots would come on and Katherine would meet them with her force, and fling them into defense of the southern counties of England. If the Scots cut through them then Katherine and Surrey had a final plan for the defense of London. They would regroup, summon a citizens’ army, throw up earthworks around the City and if all else failed, retreat to the Tower, which could be held for long enough for Henry to reinforce them from France.

Surrey is anxious that I have ordered him to lead the first attack against the Scots, he would rather wait for my force to join him; but I insist the attack shall go as I have planned. It would be safer to join our two armies, but I am fighting a defensive campaign. I have to keep an army in reserve to stop the Scots sweeping south, if they win the first battle. This is not a single battle I am fighting here. This is a war that will destroy the threat of the Scots for a generation, perhaps forever.

I too am tempted to order him to wait for me, I so want to join the battle; I feel no fear at all, just a sort of wild gladness as if I am a hawk mewed up for too long and now suddenly set free. But I will not throw my precious men into a battle that would leave the road to London open if we lost. Surrey thinks that if we unite the forces we will be certain to win but I know that there is no certainty in warfare, anything can go wrong. A good commander is ready for the worst, and I am not going to risk the Scots beating us in one battle and then marching down the Great North Road and into my capital city, and a coronation with French acclaim. I did not win this throne so hard, to lose it in one reckless fight. I have a battle plan for Surrey, and one for me, and then a position to retreat to, and a series of positions after that. They may win one battle, they may win more than one, but they will never take my throne from me.

We are sixty miles out of London, at Buckingham. This is good speed for an army on the march. They tell me it is tremendous speed for an English army; they are notorious for dawdling on the road. I am tired, but not exhausted. The excitement and—to be honest—the fear in each day is keeping me like a hound on a leash, always eager, straining to get ahead and start the hunt.

And now I have a secret. Each afternoon, when I dismount from my horse, I get down from the saddle and first thing, before anything else, I go into the necessary house, or tent, or wherever I can be alone, and I pull up my skirts and look at my linen. I am waiting for my monthly course, and it is the second month that it has failed to come. My hope, a strong, sweet hope, is that when Henry sailed to France, he left me with child.

I will tell no one, not even my women. I can imagine the outcry if they knew I was riding every day, and preparing for battle when I am with child, or even in hopes of a child. I dare not tell them, for in all truth, I do not dare do anything which might tilt the balance in this campaign against us. Of course, nothing could be more important than a son for England—except this one thing: holding England for that son to inherit. I have to grit my teeth on the risk I am taking and take it anyway.

The men know that I am riding at their head and I have promised them victory. They march well; they will fight well because they have put their faith in me. Surrey’s men, closer to the enemy than us, know that behind them, in reliable support, is my army. They know that I am leading their reinforcements in person. It has caused much talk in the country, they are proud to have a queen who will muster herself for them. If I were to turn my face to London and tell them to go on without me, for I have a woman’s work to do, they would head for home too—it is as simple as that. They would think that I had lost confidence, that I had lost faith in them, that I anticipate defeat. There are enough whispers about an unstoppable army of Scotsmen—one hundred thousand angry Highlanders—without me adding to their fears.

Besides, if I cannot save my kingdom for my child, then there is little point in having a child. I have to defeat the Scots, I have to be a great general. When that duty is done, I can be a woman again.

At night, I have news from Surrey that the Scots are encamped on a strong ridge, drawn up in battle order at a place called Flodden. He sends me a plan of the site, showing the Scots camped on high ground, commanding the view to the south. One glance at the map tells me that the English should not attack uphill against the heavily armed Scots. The Scots archers will be shooting downhill and then the Highlanders will charge down on our men. No army could face an attack like that.

“Tell your master he is to send out spies and find a way around the back of the Scots to come upon them from the north,” I say to the messenger, staring at the map. “Tell him my advice is that he makes a feint, leaves enough men before the Scots to pin them down, but marches the rest away, as if he is heading north. If he is lucky, they will give chase and you will have them on open ground. If he is unlucky he will have to reach them from the north. Is it good ground? He has drawn a stream on this sketch.”

“It is boggy ground,” the man confirms. “We may not be able to cross it.”

I bite my lip. “It’s the only way that I can see,” I say. “Tell him this is my advice but not my command. He is commander in the field, he must make his own judgment. But tell him I am certain that he has to get the Scots off that hill. Tell him I know for sure that he cannot attack uphill. He has to either go round and surprise them from the rear or lure them down off that hill.”

The man bows and leaves. Please God he can get my message through to Surrey. If he thinks he can fight an army of Scots uphill he is finished. One of my ladies comes to me the minute the messenger has left my tent. She is trembling with fatigue and fear. “What do we do now?”

“We advance north,” I say.

“But they may be fighting any day now!”

“Yes, and if they win we can go home. But if they lose we shall stand between the Scots and London.”

“And do what?” she whispers.

“Beat them,” I say simply.

10TH SEPTEMBER 1513

“Your Grace!” A page boy came dashing into Katherine’s tent, bobbed a most inadequate hurried bow. “A messenger, with news of the battle! A messenger from Lord Surrey.”

Katherine whirled around, her shoulder strap from her halberk still undone. “Send him in!”

The man was already in the room, the dirt of the battle still on him, but with the beam of a man bringing good news, great news.

“Yes?” Katherine demanded, breathless with hope.

“Your Grace has conquered,” he said. “The King of Scotland lies dead—twenty Scottish lords lie with him, bishops, earls, and abbots too. It is a defeat they will never rise up from. Half of their great men have died in a single day.”

He saw the color drain from her face and then she suddenly grew rosy. “We have won?”

“You have won,” he confirmed. “The earl said to tell you that your men, raised and trained and armed by you, have done what you ordered they should do. It is your victory, and you have made England safe.”

Her hand went at once to her belly, under the metal curve of the breastplate. “We are safe,” she said.

He nodded. “He sent you this…”

He held out for her a surcoat, terribly torn and slashed and stained with blood.

“This is?”

“The coat of the King of Scotland. We took it from his dead body as proof. We have his body, it is being embalmed. He is dead, the Scots are defeated. You have done what no English king since Edward the First could do. You have made England safe from Scottish invasion.”

“Write out a report for me,” she said decisively. “Dictate it to the clerk. Everything you know and everything that my lord Surrey said. I must write to the king.”

“Lord Surrey asked…”

“Yes?”

“Should he advance into Scotland and lay it waste? He says there will be little or no resistance. This is our chance. We could destroy them—they are utterly at our mercy.”

“Of course,” she said at once, then she paused. It was the answer that any monarch in Europe would have given. A troublesome neighbor, an inveterate enemy lay weakened. Every king in Christendom would have advanced and taken revenge.

“No. No, wait a moment.”

She turned away from him and went to the doorway of her tent. Outside, the men were preparing for another night on the road, far from their homes. There were little cook fires all around the camp, torches burning, the smell of cooking and dung and sweat in the air. It was the very scent of Katherine’s childhood, a childhood spent for the first seven years in a state of constant warfare against an enemy who was driven backwards and backwards and finally into slavery, exile and death.

Think, I say to myself fiercely. Don’t feel with a tender heart, think with a hard brain, a soldier’s brain. Don’t consider this as a woman with child who knows there are many widows in Scotland tonight, think as a queen. My enemy is defeated, the country lies open before me, their king is dead, their queen is a young fool of a girl and my sister-in-law. I can cut this country into pieces, I can quilt it. Any commander of any experience would destroy them now and leave them destroyed for a whole generation. My father would not hesitate; my mother would have given the order already.

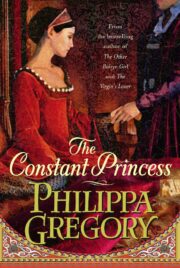

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.